The San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA) was hit with a ransomware attack on Friday, causing fare station terminals to carry the message, “You are Hacked. ALL Data Encrypted.” Turns out, the miscreant behind this extortion attempt got hacked himself this past weekend, revealing details about other victims as well as tantalizing clues about his identity and location.

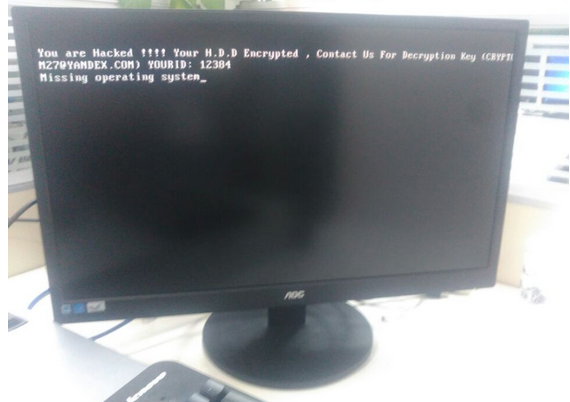

A copy of the ransom message left behind by the “Mamba” ransomware.

On Friday, The San Francisco Examiner reported that riders of SFMTA’s Municipal Rail or “Muni” system were greeted with handmade “Out of Service” and “Metro Free” signs on station ticket machines. The computer terminals at all Muni locations carried the “hacked” message: “Contact for key (cryptom27@yandex.com),” the message read.

The hacker in control of that email account said he had compromised thousands of computers at the SFMTA, scrambling the files on those systems with strong encryption. The files encrypted by his ransomware, he said, could only be decrypted with a special digital key, and that key would cost 100 Bitcoins, or approximately USD $73,000.

On Monday, KrebsOnSecurity was contacted by a security researcher who said he hacked this very same cryptom27@yandex.com inbox after reading a news article about the SFMTA incident. The researcher, who has asked to remain anonymous, said he compromised the extortionist’s inbox by guessing the answer to his secret question, which then allowed him to reset the attacker’s email password. A screen shot of the user profile page for cryptom27@yandex.com shows that it was tied to a backup email address, cryptom2016@yandex.com, which also was protected by the same secret question and answer.

Copies of messages shared with this author from those inboxes indicate that on Friday evening, Nov. 25, the attacker sent a message to SFMTA infrastructure manager Sean Cunningham with the following demand (the entirety of which has been trimmed for space reasons), signed with the pseudonym “Andy Saolis.”

“if You are Responsible in MUNI-RAILWAY !

All Your Computer’s/Server’s in MUNI-RAILWAY Domain Encrypted By AES 2048Bit!

We have 2000 Decryption Key !

Send 100BTC to My Bitcoin Wallet , then We Send you Decryption key For Your All Server’s HDD!!”

One hundred Bitcoins may seem like a lot, but it’s apparently not far from a usual payday for this attacker. On Nov. 20, hacked emails show that he successfully extorted 63 bitcoins (~$45,000) from a U.S.-based manufacturing firm.

The attacker appears to be in the habit of switching Bitcoin wallets randomly every few days or weeks. “For security reasons” he explained to some victims who took several days to decide whether to pay the ransom they’d been demanded. A review of more than a dozen Bitcoin wallets this criminal has used since August indicates that he has successfully extorted at least $140,000 in Bitcoin from victim organizations.

That is almost certainly a conservative estimate of his overall earnings these past few months: My source said he was unable to hack another Yandex inbox used by this attacker between August and October 2016, “w889901665@yandex.com,” and that this email address is tied to many search results for tech help forum postings from people victimized by a strain of ransomware known as Mamba and HDD Cryptor.

Copies of messages shared with this author answer many questions raised by news media coverage of this attack, such as whether the SFMTA was targeted. In short: No. Here’s why.

Messages sent to the attacker’s cryptom2016@yandex.com account show a financial relationship with at least two different hosting providers. The credentials needed to manage one of those servers were also included in the attacker’s inbox in plain text, and my source shared multiple files from that server.

KrebsOnSecurity sought assistance from several security experts in making sense of the data shared by my source. Alex Holden, chief information security officer at Hold Security Inc, said the attack server appears to have been used as a staging ground to compromise new systems, and was equipped with several open-source tools to help find and infect new victims.

“It appears our attacker has been using a number of tools which enabled the scanning of large portions of the Internet and several specific targets for vulnerabilities,” Holden said. “The most common vulnerability used ‘weblogic unserialize exploit’ and especially targeted Oracle Corp. server products, including Primavera project portfolio management software.”

According to a review of email messages from the Cryptom27 accounts shared by my source, the attacker routinely offered to help victims secure their systems from other hackers for a small number of extra Bitcoins. In one case, a victim that had just forked over a 20 Bitcoin ransom seemed all too eager to pay more for tips on how to plug the security holes that got him hacked. In return, the hacker pasted a link to a Web server, and urged the victim to install a critical security patch for the company’s Java applications.

“Read this and install patch before you connect your server to internet again,” the attacker wrote, linking to this advisory that Oracle issued for a security hole that it plugged in November 2015.

In many cases, the extortionist told victims their data would be gone forever if they didn’t pay the ransom in 48 hours or less. In other instances, he threatens to increase the ransom demand with each passing day.

WHO IS ALI REZA?

The server used to launch the Oracle vulnerability scans offers tantalizing clues about the geographic location of the attacker. That server kept detailed logs about the date, time and Internet address of each login. A review of the more than 300 Internet addresses used to administer the server revealed that it has been controlled almost exclusively from Internet addresses in Iran. Another hosting account tied to this attacker says his contact number is +78234512271, which maps back to a mobile phone provider based in Russia.

But other details from the attack server indicate that the Russian phone number may be a red herring. For example, the attack server’s logs includes the Web link or Internet address of each victimized server, listing the hacked credentials and short notations apparently made next to each victim by the attacker. Google Translate had difficulty guessing which language was used in the notations, but a fair amount of searching indicates the notes are transliterated Farsi or Persian, the primary language spoken in Iran and several other parts of the Middle East.

User account names on the attack server hold other clues, with names like “Alireza,” “Mokhi.” Alireza may pertain to Ali Reza, the seventh descendant of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, or just to a very common name among Iranians, Arabs and Turks.

The targets successfully enumerated as vulnerable by the attacker’s scanning server include the username and password needed to remotely access the hacked servers, as well as the IP address (and in some cases domain name) of the victim organization. In many cases, victims appeared to use newly-registered email addresses to contact the extortionist, perhaps unaware that the intruder had already done enough reconnaissance on the victim organization to learn the identity of the company and the contact information for the victim’s IT department.

The list of victims from our extortionist shows that the SFMTA was something of an aberration. The vast majority of organizations victimized by this attacker were manufacturing and construction firms based in the United States, and most of those victims ended up paying the entire ransom demanded — generally one Bitcoin (currently USD $732) per encrypted server.

Emails from the attacker’s inbox indicate some victims managed to negotiate a lesser ransom. China Construction of America Inc., for example, paid 24 Bitcoins (~$17,500) on Sunday, Nov. 27 to decrypt some 60 servers infected with the same ransomware — after successfully haggling the attacker down from his original demand of 40 Bitcoins. Other construction firms apparently infected by ransomware attacks from this criminal include King of Prussia, Pa. based Irwin & Leighton; CDM Smith Inc. in Boston; Indianapolis-based Skillman; and the Rudolph Libbe Group, a construction consulting firm based in Walbridge, Ohio. It’s unclear whether any of these companies paid a ransom to regain access to their files.

PROTECT YOURSELF AND YOUR ORGANIZATION

The data leaked from this one actor shows how successful and lucrative ransomware attacks can be, and how often victims pay up. For its part, the SFMTA said it never considered paying the ransom.

“We have an information technology team in place that can restore our systems and that is what they are doing,” said SFMTA spokesman Paul Rose. “Existing backup systems allowed us to get most affected computers up and running this morning, and our information technology team anticipates having the remaining computers functional in the next two days.”

As the SFMTA’s experience illustrates, having proper and regular backups of your data can save you bundles. But unsecured backups can also be encrypted by ransomware, so it’s important to ensure that backups are not connected to the computers and networks they are backing up. Examples might include securing backups in the cloud or physically storing them offline. It should be noted, however, that some instances of ransomware can lock cloud-based backups when systems are configured to continuously back up in real-time.

That last tip is among dozens offered by the Federal Bureau of Investigation, which has been warning businesses about the dangers of ransomware attacks for several years now. For more tips on how to avoid becoming the next ransomware victim, check out the FBI’s most recent advisory on ransomware.

Finally, as I hope this story shows, truthfully answering secret questions is a surefire way to get your online account hacked. Personally, I try to avoid using vital services that allow someone to reset my password if they can guess the answers to my secret questions. But in some cases — as with United Airlines’s atrocious new password system — answering secret questions is unavoidable. In cases where I’m allowed to type in the answer, I always choose a gibberish or completely unrelated answer that only I will know and that cannot be unearthed using social media or random guessing.

Does anyone know the frequency of ransomware encryption of databases? It is possible for ransomware to do this but is it happening?

At my computer shop, we get about 6 ransomware infections a month. Sometimes it’s grandma with the infection, sometimes it’s a hotel’s server.

Search on Cryptowall 4. In an article, I remember seeing content about encrypting databases, sabotaging backups, and the estimated revenue.

Yes, the encryption of databases by ransomware is happening. For example, one of the most commonly families of ransomware dropped by exploit kits is Cerber. Within Cerber’s configuration files it specifies certain file types that it will encrypt. Here are a couple of file types related to databases that Cerber will encrypt “.sqlitedb”,”.sqlite3″,”.sqlite” and “.sql”. One thing I find interesting about Cerber is they will kill a number of processes related databases. This is done to make sure there are no open handles to the files by the database process. These open handles could prevent the encrypting of the files. Here are a couple process names that Cerber specifically kills related to database “sqlagent.exe”,”sqlbrowser.exe”,”sqlservr.exe”,”sqlwriter.exe” and “oracle.exe”.

Did someone seriously write an entire article talking about how backups saved them a “bundle” but then not even mention the fact that they have unsecured, unpatched systems connected to the Internet in some fashion? (despite the fact they gave away fares for a day and spent a huge amount of resources on this ordeal, which surely cost more than the ransom payment itself)….

@DK +1

I was thinking the exact same thing…

To be fair, there was a huge amount of information in this article before the final paragraph touted the importance of backups. That’s what I got out of it.

Implied in your response, but not explicitly stated: These restored systems will just get hacked again if they aren’t patched or secure in some manner first before they are exposed again.

According to their operating budget, fares are about $550,000 per day, but looks like that includes buses and cable cars as well as the trains. I would also assume that a great number of people use monthly passes.

More importantly, there’s no guarantee that paying the ransom would have gotten them back up on their feet any more quickly than using the backups. Or that the attacker would be kind enough to remove any backdoors that may have been put in place.

There has been some claim (and at least one article) that the initial intrusion vector was a malware-laden utility (downloaded via tor) used by an administrator.

Its the weakest links – A company hires individuals to “do their job” and some will do that more so than others. People leave a corporation and no one picks up that responsibility, or does not do it at diligently as the person that departed.

Add in the “authorization creep”, people having too much privileges on a network that will aid in the spread of disasters such as this. If a network doesn’t have a great file structure with strict rights/privileges, its a haven for cryptoware.

Outsiders probably don’t know the exact corporate IT composure and whether the IT area of this Metro IT team lacks skills in a particular area, at this point, its all guesses. It could have been a single instance of a missed file out of hundreds of servers. It only takes one.

Its like a day at the races, once a vulnerability is released, a patch is released, its tested to see if it can be reverse engineered to provide a way to look up the vulnerability. If the patch is not available for a pretty long time from the vendor and there is no way to mitigate the issue, its hard to point a finger at a company that is trying to maintain, and not giving into the hacker(s) demands.

This company is better off than most. Looking at the rest in the list, “hype-pathetically” speaking, they paid either for the ease, or they had no idea how to get back up quickly, or did not have a good set of backups. The ones that have paid might have a higher chance of this occurrence happening again, over the company that will work through the Disaster Recovery Plan and see that bringing the system back online though painful, was successful.

The doubled edge sword is that as networks are being built, very little companies will think forward when it comes to growth and offer segmented vlans and break the network up into smaller chunks to avoid a complete obliteration of a flat network. When the company becomes large and offers a service to many, it becomes a huge task to make big changes fast.

There is not a industry standard, universal way to make these sort of issues go away. All it takes is on inadvertent click, or missing one patch and it can be game over.

Sometimes, it’s not about the money, its about sending a message.

They didn’t retrieve data from backup, they did a fresh deploy on those systems.

Can someone explain why it isn’t possible to make the Bitcoins in question useless (or at least, far less valuable) to the attacker simply by publicly listing them as stolen?

My limited understanding of the technology involved suggests that as Bitcoins are transferred from person to person they still retain their identity. If a Bitcoin exchange were to purchase stolen Bitcoins, wouldn’t they be on the hook for receiving stolen property? How would miscreants monetize Bitcoin ransoms if they couldn’t exchange them for real currency?

(I presume there’s something about the technology, or perhaps the politics, that I have misunderstood. It would just be nice to know what, exactly.)

You are assuming they are just cashing them out at an exchange. They could be used to buy all sorts of good and services, and then cash out in this laundered fashion.

Legitimate merchants would presumably also want to avoid receiving stolen Bitcoin. Perhaps the black market, but if the Bitcoin can never leave the black market, surely their value would at best be severely reduced?

Bitcoin address is just a hash (number). Unless you are the owner of that address, you have no clue who owns it. As a Bitcoin user, you can create any number of Bitcoin address, and you can choose to publish (on the regular WWW) zero to any number of your accounts’ address.

With that arrangement, given the fact that there are billions of addresses already out there, hacker can make 1 million addresses, and transfer the fund partially or fully between them, and there would be no way you can know which is his.

But you can see all the transfers, can’t you? So you still know which addresses have received the ransom payment. You can’t tell whether they still belong to the original attacker or have been transferred to someone else, but that doesn’t necessarily matter.

By way of analogy, if a stolen painting is found in your house, the government may not be able to prove whether or not you stole it yourself or bought it from the thief, but you can still be prosecuted.

Bitcoin transfers require a public-private key pair, a process that can be used to obfuscate ownership, rather than publishing it. I’ve never been able to figure out what Bitcoin is good for (if you’re not paranoid about nation-states issuing currency as they have for the last few thousand years) other than protecting illegal activity such as drug dealing, arms dealing, and ransomware. It’s probably time to make Bitcoin transactions illegal, if only to discourage those activities.

As I understand it, it obfuscates ownership, but not the identity of the Bitcoin. Even years later, you could still point at a particular Bitcoin and say “that Bitcoin was used to pay such-and-such a ransom”. You may not know who owns it now, and if ownership has been transferred you may not know who any of the intermediate parties were, but if somebody offers it to you in payment, you would still know you shouldn’t take it.

They’re also good for tax evaders, since you know nobody smaller than the exceedingly few retailers willing to accept bitcoin are reporting it as income.

They like to say it’s because of nation state currency and big brother and all the other tinfoil hat nuttery, but what it’s really about is avoiding paying their fair share of taxes.

Was thinking the same thing. Why do these articles never piblicize the bitcoin address? That would seem one of the easier ways to at least taint the address. On bitcoinwhoswho.com you can go so far as to flag scam addresses

Even supposing there were some trusted realtime blacklist of bitcoins (which sounds hard: you have to ensure not only that enough people check your blacklist, but that it’s impossible to blacklist bitcoin that wasn’t yours to begin with), it wouldn’t help this situation. It’ll just mean the receiver of the ransom bitcoins waits until cashing them out (which could be a pretty quick operation — they don’t even need to trade the bitcoins for dollars, only a mix of other bitcoins) before handing over the decryption key.

Then if you invalidate the bitcoins *before* paying them, you won’t get your data back (because the attacker won’t be able to liquidate them, and therefore won’t accept them as payment), and if you invalidate them afterwards, you don’t hurt the attacker, only the poor sap who unwittingly accepted the ransom moments before it was deactivated.

I was assuming a state actor, so trust is pretty much irrelevant. You might or might not trust your government but either way you’re probably going to want to avoid getting arrested if at all possible.

Your second point makes much more sense, though, provided you assume that the hypothetical blacklist operator cares about the health of the Bitcoin economy. I wouldn’t want to bet on it, but it sounds at least plausible.

… I mean, OK, if it were up to me I’d probably go ahead with the blacklist and if you wanted to accept payment in Bitcoins you’d just have to accept the risk that you might lose your money, just the same as with credit cards. But I can understand why people might be reluctant to take that step.

So, all in all, I think this is the answer I was looking for. Thanks!

Just had to get that dog in at United didn’t you? LOL! Great article!

Will the hacker hacker get hacked?

I’ve heard there are two types of computer users – those who know they’ve been hacked and those who don’t know they’ve been hacked.

I suppose there should be honor among thieves. But, in cyberspace, no one knows you’re a hacker, so ….

Secret questions are definitely a problem, but so are draconian password restrictions. Delta Airlines, for example, does not permit any “special characters” to be used in passwords.

I can get by without special characters so long as they don’t have an exceedingly short character limit. I know one SAAS provider who didn’t allow special characters and also allowed a max password length of 12 characters.

Hmmm … turns out crime does pay. Hope I never get Cryptolocked!

Is cryptolocking even illegal under current law, though? I get that it should be, but with how slow law is to catch up to tech, I wouldn’t be at all surprised if ransomware wasn’t technically illegal.

For corporate and if possible, home PC’s, they need to be:

1. Patched (not just OS patches, but major apps as well, such as java, flash, MS Office, etc.)

2. Endpoint protection needs to be advanced in nature (malware, file and web reputation, behavior analysis, etc), up to date and running all the time

3. Backups: Secure solutions which backup on a regular basis and are themselves protected from being victimized by a cryptolocked host.

4. Admin access restricted. This is a tough one for most enterprises, but with some work, you can restrict admin activities while still enabling innovation and corporate culture.

And none of those things will actually help you when someone opens a Word doc emailed to them.

(Well, the backup will get you back on your feet, I suppose)

Turn off Word Macros. That’s the single biggest threat, and it avoids your AV, your firewall, your everything, and for what? A feature no – one uses anyway!

While it is of course wise to be careful about using secret questions for security, it seems like a very weird warning to put at the end of the article in terms of the context of this incident. The only incidence of “hacking by guessing secret questions” was when the hacker himself was hacked. It’s like you’re advising future malicious hackers on how not to get hacked.

I had the misfortune to have to recover from some ransomeware. My own fault. I got an email which I was sure was a problem but I was curious about the attachment so I opened it in edit mode, then got bored reading the code and went off to do something else.

Unfortunately I must have run the script ‘cos it was running in the background. One of my external hard drives was showing activity, which I found strange, so I powered it off. Then I got the ransomware message (your money or your data). It had encrypted every photo and music file it could find (300Gb worth) and renamed them with the extension .cryptd. Send us bitcoins and we’ll restore your data.

Since Google is my best friend, I asked and found a website that had a program that would decrypt all the messed up data. That worked astonishingly well. It restored most files and for some that it couldn’t decrypt, I found most of them on backup. In the end, the only files I could not recover were some Playboy Centerfold pictures – I have no idea why (except they weren’t on backup).

Since that incident, I’ve become much more serious about backup. I now use two external hard drives (3Tb each – they’re actually internal hard drives in an external case) and wrote a script that will do either a full backup or a partial one. Having two backup drives, I keep one of them offsite (in my van) and swap them every month or two. I run a full backup on an occasional basis and a partial backup runs automatically every day. A full backup is just a copy of all my data, whereas a partial backup is just the changes since the last partial backup. Recovery from a problem would be a manual task. I only backup my data files – software can be reacquired from source.

Link to that mysterious website? Sounds like BS…

Brian, just a few weeks ago you reported that hackers are good people and should protected and honored and rewarded for their efforts, remember publishing this?

“hacker /ha-ker/ one who enjoys the intellectual challenge of creatively overcoming limitations.”

The glamour and reward of hacking is very enticing in your blog, better than any hollywood movie.

Troll much?

“Hacker” is like “gunslinger,” the description of a skill which can be used for good or ill.

Don’t be counterproductive.

Ali Reza is a popular first name in Farsi, and Mokhi is a nickname that can be derived from a last name or more likely from “Mokhi” which means brain or head and in the way it’s used roughly translates to “brainiac”. I’d be happy to try and help translate the Farsi notations if they’re available.

Most infections are coming from end-users who lack proper education about how the internet works. There will always be stupid people and no amount of training or education will help them. Hence the day old just of the button that says “dont push me” and everyone does. We are curious creatures.

It’s attachments being opened from the prince of nigera. Or the dig bick emails that have an attachment on with secrets on how to get a 9 inch penis.

We are stupid.

But enterprise business suffer because they don’t want to spend a couple operative loss hours teaching their employees things or spending money on prevention.

We are all prone to get something every now and then its inevitable. But when people are still bringing there $299.99 dells in shops because its slow – and there are 40 casino games on it and the desktop has 90 installers…. I digress

Out of curiosity, since you’ve seen the emails, when was the communication to CDM Smith made? They’re denying that it ever happened.

Maybe the fare systems should be offline and read information directly from the card, or directly from the farebox itself. And if they do want to stay online, I recommend they use a more secure OS like Linux.

I think probably comes from a india madhya pradesh I’m not at the computer, Failed to send my message. Please contact the administrator by another method. Please verify

Kudos for answering the security questions. What are the chances that he would know the answer to the security question.

His security questions must be stupid.

What is your favorite color?

What is your last name?

What is your password?

[What]

What, is the airspeed velocity of an unladen swallow

Any updates/ or status on these events?

I’ll ask again, but is software like Anti Ransom [1] useful to prevent this attacks?

[1] http://www.security-projects.com/?Anti_Ransom

Thanks,