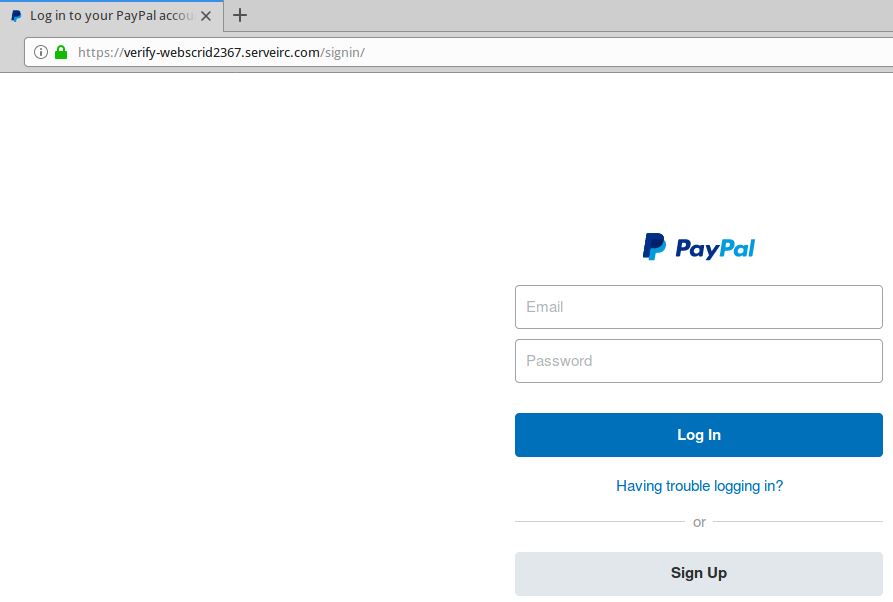

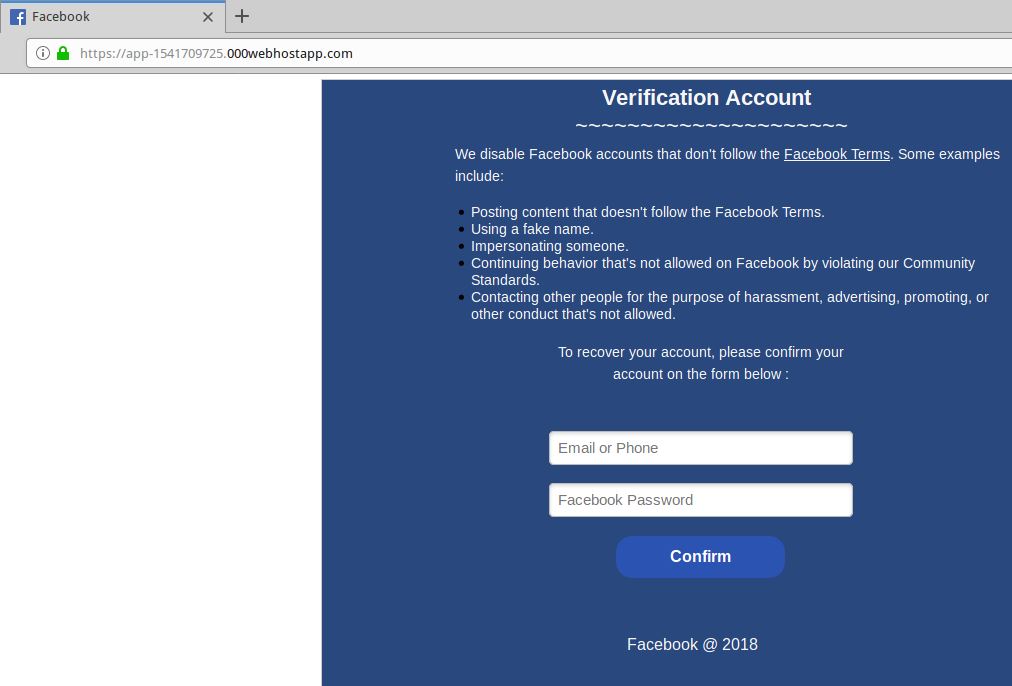

Maybe you were once advised to “look for the padlock” as a means of telling legitimate e-commerce sites from phishing or malware traps. Unfortunately, this has never been more useless advice. New research indicates that half of all phishing scams are now hosted on Web sites whose Internet address includes the padlock and begins with “https://”.

Recent data from anti-phishing company PhishLabs shows that 49 percent of all phishing sites in the third quarter of 2018 bore the padlock security icon next to the phishing site domain name as displayed in a browser address bar. That’s up from 25 percent just one year ago, and from 35 percent in the second quarter of 2018.

This alarming shift is notable because a majority of Internet users have taken the age-old “look for the lock” advice to heart, and still associate the lock icon with legitimate sites. A PhishLabs survey conducted last year found more than 80% of respondents believed the green lock indicated a website was either legitimate and/or safe.

In reality, the https:// part of the address (also called “Secure Sockets Layer” or SSL) merely signifies the data being transmitted back and forth between your browser and the site is encrypted and can’t be read by third parties. The presence of the padlock does not mean the site is legitimate, nor is it any proof the site has been security-hardened against intrusion from hackers.

Most of the battle to combat cybercrime involves defenders responding to offensive moves made by attackers. But the rapidly increasing adoption of SSL by phishers is a good example in which fraudsters are taking their cue from legitimate sites.

“PhishLabs believes that this can be attributed to both the continued use of SSL certificates by phishers who register their own domain names and create certificates for them, as well as a general increase in SSL due to the Google Chrome browser now displaying ‘Not secure’ for web sites that do not use SSL,” said John LaCour, chief technology officer for the company. “The bottom line is that the presence or lack of SSL doesn’t tell you anything about a site’s legitimacy.”

The major Web browser makers work with a number of security organizations to index and block new phishing sites, often serving bright red warning pages that flag the page of a phishing scam and seek to discourage people from visiting the sites. But not all phishing scams get flagged so quickly.

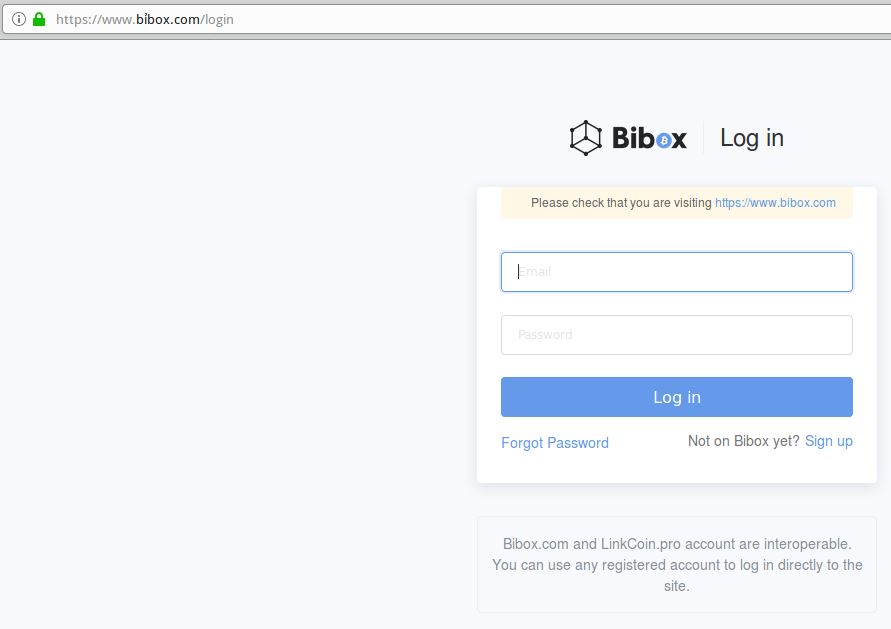

I spent a few minutes browsing phishtank.com for phishing sites that use SSL, and found this cleverly crafted page that attempts to phish credentials from users of Bibox, a cryptocurrency exchange. Click the image below and see if you can spot what’s going on with this Web address:

This live phish targets users of cryptocurrency exchange Bibox. Look carefully at the URL in the address bar, and you’ll notice a squiggly mark over the “i” in Bibox. This is an internationalized domain name, and the real address is https://www.xn--bbox-vw5a[.]com/login

Load the live phishing page at https://www.xn--bbox-vw5a[.]com/login (that link has been hobbled on purpose) in Google Chrome and you’ll get a red “Deceptive Site Ahead” warning. Load the address above — known as “punycode” — in Mozilla Firefox and the page renders just fine, at least as of this writing.

This phishing site takes advantage of internationalized domain names (IDNs) to introduce visual confusion. In this case, the “i” in Bibox.com is rendered as the Vietnamese character “ỉ,” which is extremely difficult to distinguish in a URL address bar.

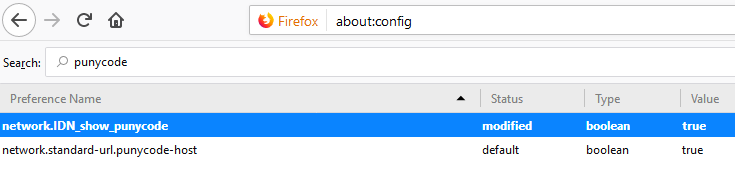

As KrebsOnSecurity noted in March, while Chrome, Safari and recent versions of Microsoft’s Internet Explorer and Edge browsers all render IDNs in their clunky punycode state, Firefox will happily convert the code to the look-alike domain as displayed in the address bar.

If you’re a Firefox (or Tor) user and would like Firefox to always render IDNs as their punycode equivalent when displayed in the browser address bar, type “about:config” without the quotes into a Firefox address bar.

Then in the “search:” box type “punycode,” and you should see one or two options there. The one you want is called “network.IDN_show_punycode.” By default, it is set to “false”; double-clicking that entry should change that setting to “true.”

I support and use “lets encrypt” ( https://letsencrypt.org/ ) but unfortunately, its probably working against us at this point….

No, the availability of low-cost certificates improves the overall security of the web.

The browser makers complicate the situation by continuing to misrepresent what is accomplished by using HTTPS connections.

“Misrepresent” seems kinda strong and or wrong.

The problem is: you’re trying to get end-users to look at fairly complicated signs to ascertain whether or not they’re about to drive off a cliff.

And these are users who- on coin-flip odds- may not even recognize that a web browser is a program you browse the internet with (they’ll call it “the internet” usually), let alone what “all that gobletygook” near the top of the window signifies.

The truth is that figuring this stuff out is reasonably complicated, and experts are looking for traffic-light-like signals to communicate to those users what is and is not okay.

At one time- not that long ago- ‘https’ was a fairly solid indicator you had an upstanding site, the sands have since shifted.

The habits/advice will be harder to shift, and will probably persist for the next decade… or more.

I don’t think browser developers are interested in deception here. They’re interested in designing a UI that’s meaningful to their end-users.

And I don’t envy them in that pursuit.

I dont think its that we are trying to get users to look at fairly complicated signs, its more like we are trying to get morons to read fairly simple signs, but these are the same people who need car manufacturers to explicitly tell them that cruise control was not auto pilot, long before self driving was even on the radar.

Whatever they are, and however reasonable or unreasonable their ignorance, they’re still your end users.

I’d think the ~last~ thing you’d be trying for is to confuse them further.

As a “coder since the 80’s” which now has fixed probably over a hundred of friends and their friends pcs, I totally agree with SkunkWerks.

Not only it happens more often than not that people have no idea what a browser is when I ask them which one they’re using, but they have it named as “internet” on their desktop (no idea who does that for them though).

I found extremely difficult to explain them what a browser is, let alone explain them what internet is (which is not just browsing websites, for those who wonders why would it be so difficult).

Just as a test, ask anyone, and maybe even yourselves, what, in details, is an operating system: almost nobody would be able to explain it either correctly or at all, and everybody uses an operating system this day, in their routers, phones, computers, and sometimes even televisions or set-top boxes.

All of this stuff is “easy” for some people because we played with it since we were kids, or studied it later but more deeply than the average person, but it really is a really overcomplicated concept for those who aren’t into technology or aren’t smarter than the average.

And I’ll tell you more: most of the people that believes they “got it” in fact didn’t, no matter what the subject is.

I think this argument is problematic. Many years ago I learned that the “morons” might be smarter than me in many areas: brain surgeons, mathematicians, musicians, physicists, engineers or people who could clobber me at chess but who are not tech savvy. The real key is to make it as easy as possible for people to make the right choices. It is pointless to try to go on a crusade to educate them technically. They don’t have the disposition or the chops to change. Even as a computer scientist and computer engineer that has worked in the security field for two AV companies, I don’t want to have to think about security. I use my computer as a tool and I want it to “just work”. I am not saying that we eliminate trying to educate people but that we realize that approach is limited and try to figure out better ways of identifying and shutting down Phishing sites and improving our detection for users. It is always a multi-layer deal.

I agree with John Gardner.

The most basic lesson in any Comp Sci course in Human Interface design is that systems need to be adapted to the expectations of the users.

Calling users names or making them feel dumb isn’t going to have a positive effect on your profit margins or in their comfort, productivity, and security.

This SSL certificate that was issued for this phish site wasn’t even from Let’s Encrypt.

Blaming TLS|Let’sEncrypt for phishing sites is like blaming the tuna fish for botchalism.

Seems to me that the only noteworthy thing about phishing pages moving to TLS is that we’ve finally successfully normalized encryption to such an extent than even amateur phishers must participate to be taken seriously.

Firefox shows a red screen now. I don’t think that it’s bad that criminals use TLS now. It was just a matter of time. The punycode thing is much more dangerous.

Not for me…

The only solution is to educate more people about this issue, that’s if they are willing to learn about the dangers of phishing scams. Most people can care less, until they get scammed .

That’ll be “can’t” care less. If you don’t care at all, you could not care less. If you can /care/ less then, obviously, you care at least a little bit.

I’m all in favour of living languages evolving but it helps no-one to say the exact opposite of what you mean. That’s just sick.

Or make the browsers explain it…

When a user has their keyboard set to English, throw up an intermediate screen when they access a website with a non-English name.

“You’re about to follow a link or open a website in Vietnamese, but your keyboard is set to English. The website #!$!#-dot-com was created 4 months ago. Would you like to continue?”

This is the best idea, and should be default.

🙂

Bad response from lets encrypt to flight against phishing site using their SSL cert.

another great site to see live phishing links is

https://openphish.com/

burn linux tails to a dvd and boot from that so your system wont get infected when clicking on the links. I did this so I can see how real some of these phishing links really look.

I would not click the links on your main system that has all your information on it. especially if you’re using Windows.

It really is a shame that EV certs (green bar, not just green lock) haven’t become more common place, particularly where entering sensitive information.

Both these examples demonstrate the weakness of domain validation TLS. Let’s Encrypt provides a great service to enable every site to provide encrypted traffic, but the vetting is not good enough when you need to share sensitive data . Who are you sharing this sensitive data with? An EV cert would not only answer this question by it would make it more difficult for these phishing organizations to hide.

EV certificates are also almost snakeoil. They are expensive, and the fact is that they verify very little.

But, well, at least you have to use a credit card, so point to start a fraud investigation.

EV certs are expensive, primarily because of the human validation, this stuff is not automated. The punycode problem would have been caught and an EV cert would not have been issued. In addition to the credit card, a Dun & Bradstreet registration of the company would be validated, so this would require well established mailing addresses and names of company officers.

Yes EV certs are expensive, so don’t use them everywhere. Let’s Encrypt has a great service, but if you are sharing a credit card or any KYC bank info it is a shame EV isn’t used more often

Not only are they HTTPS:// but the example Brian Krebs uses gets an “A” grade from the Qualys company’s SSL Server Test

https://www.ssllabs.com/ssltest/analyze.html?d=www.xn--bbox-vw5a.com

I don’t think you understand how the internet works lol. Go read an RFC and come back to tell us how some bs scanner service is relevant, let alone useful in regards to social engineering. Same applies to SSL/this article.

That is because we should NOT be conflating between the security of the connection, and the legitimacy of the website’s content or intention.

SSL Labs tests only these things:

Certificate

Protocol Support

Key Exchange

Cipher Strength

… and makes no assumptions or declarations about site content or intention.

Another fantastic article. Thanks for all the great information you give.

Let’s Encrypt is a pointless and stupid assault on Internet Security.

Not everything on the Internet needs to be encrypted. TLS prevents snooping of content across networks and backbones – traditionally the realm of government espionage; non-state criminals tend to focus on endpoints where encryption is usually moot – but it does not prevent metadata snooping (the hostname is visible in the TLS exchange, and quite a bit can be inferred by traffic analysis without breaking encryption).

Was SSL/TLS intended to indicate more than a match between a domain name and what’s displayed on the site? No. But because it costs money and effort to enable, it colloquially became an indication that something of importance (worth protecting) was going on, and this strongly correlated with legitimate commerce or information exchange. This is natural economics at work, and doesn’t require any nudges.

Let’s Encrypt sets this on fire – and while I think the arguments for doing so are very weak, they’re free to disagree and do so – but it brings absolutely nothing to the table to replace the information (indication of important information exchanges worth trusting) they’re very deliberately destroying. I don’t know if they’re just criminally negligent or a deliberate cybercriminal effort; it’s difficult to distinguish the two. But, hey, congratulations, Let’s Encrypt. You’ve now made removed the average Internet user’s ability to distinguish between the security level that banks and social media use vs. some crappy malware-infested cat picture aggregation blog or strictly malicious phishing site. Should the average user learn to distinguish between padlocks and green bars and whatever other nonstandard things are out there that some jackass wannabe do-gooder will set on fire next week for some similarly stupid reason? Probably, but they won’t. Getting them to look for a padlock was a nightmare-level challenge. And at the end of the day, all for naught.

The most likely colloquial replacement for the padlock will be going back to branding – even harder to prevent spoofing of, and deeply against the more egalitarian principles that created the initial excitement about the Internet. If it’s impossible to trust Alice and Bob’s Small Business Web Shop, them people go to Amazon.com or WalMart.com.

>Let’s Encrypt is a pointless and stupid assault on Internet Security.

>Not everything on the Internet needs to be encrypted. >TLS prevents snooping of content across networks and backbones

Nowadays, with WIFI, makes more sense than before.

The problem is that SSL is a broken security system, it is the wrong “threat model”. The SSL system was designed to spies etc, where the communication was hostile and the ends were secure. Now we are the other way around. The ends are insecure, user PC and web, are easily hacked, where ISP channels are seldom hacked.

It looks like thieves come into the house through a window and there is seller that each years sells us a more strong and expensive reinforced door and a better lock while thieves keep using window.

Check this

http://www.iang.org/ssl/rescorla_1.html

With Public WiFi…

This argument makes ZERO SENSE.

If you are reliant on WPA2 alone, that is stupid.

You really cannot trust your local area transport most of the time. There needs to be a layer of security between endpoints and destination domain.

It is called defense in depth, layered security.

“Not everything on the Internet needs to be encrypted.”

But who makes that determination?

“TLS prevents snooping of content across networks and backbones…”

Um… do you forget about public wifi?

For most people, TLS is the ONLY layer of security that will allow them to do business in public.

This is defense in depth. Endpoint is important, but without TLS on even mundane websites, the endpoint becomes MORE vulnerable to injection of malicious code.

The prevalence of unencrypted web traffic was a HUGE problem for a long time. It was a major vector for initial attack. Let’s Encrypt allows every mom and pop website to at least have that very basic protection.

Just because TLS doesn’t do EVERYTHING, doesn’t mean it is harmful. It just means that browsers need to step up and educate the users about more attack vectors (which they are doing with ‘known’ phishing sites). I think they can do more.

You are getting hung up on a 16×16 image of a padlock, as if it could convey all the information a user would need to determine the holistic security posture of a website. Not just transport security, but site content, webmaster intention, and all the other nuance. It cannot. The padlock can only convey information about transport security. For anything further, you need more UI elements… such as a big red warning screen that requires user interaction… like browsers ARE doing.

You put too much emphasis on a padlock, and thus, put too much blame on Let’s Encrypt… for contributing to a problem it was never meant to even address.

Fraudsters never sleep.

They work hard to earn daily money.

I guess they work harder then anyone.. I guess 7 days week.

To be fraudster scammer its lifestyle.. Its well payed but i guess they have to work hard to succeed in this field of business.

Good ol’ homographic attack

Thank you for a great article. Firefox is now fixed. My eyes are not as young as they once were so I did not see the little mark. I changed about:config and all is well. Thank you for all you do.

Great article. As defenders, we can leverage the certificate transparency logs to identify possible phishing domain or typosquatting domains. Facebook has a free service that alerts on suspicious domains that a user subscribes to that is looking at certificate transparency logs

https://medium.com/@e_rupert/detecting-phishing-urls-from-certificate-transparency-logs-and-facebook-1e708edcaee0

Great news everyone. A few weeks ago I found another scammer posing as a staffing company. He was sloppy and set up multiple job posting sites with the goal of conning his victims out of Personal Identifying Information (PII). I found that he was using the same hosting company (BlueHost) for all of his scams. I sent multiple warning to the BlueHost”s compliance email. They seemed to be moving slow so I increased the importance of the issue by pointing out what they were not doing on my blog. It seems they got the message and shut down this latest scammer.

https://fakestaffing.blogspot.com

The scammer that I have been following for three years now is still up and still using DreamHost in California. They seem to like getting dirty money and leaving his domains up so that he can continue to pose as staffing recruiter and get SSNs and DOBS. He still has multiple fake staffing company domains going like this one:

http://www.itmcsginc.com

Brian, it’s TLS (or “Transport Layer Security”.) SSL has been deprecated.

Another problem is the browsers using the “green lock” rather than a plain lock. The “green lock” in my browser means “EV Validated Certificate” which has a higher level of verification such as a Dun&Bradstreed lookup, etcetc, and is also more expensive.

That your browser is using a green lock for a non-EV certificate (verified by visiting bibox.com) is problematic.

Shoot!! You can get pwned so easily by drive by ads at actual legitimate sites, that it isn’t even funny. NO site is safe enough anymore. Even KOS makes me nervous, but I just keep coming back for more.

I am glad to hear web site security is taken seriously by even the most fraudulent around us.

Anyone else annoyed that Firefox (and other browsers) have decided that only showing the root domain in bold is what us users want?

The fix is

about:config

Search for:

browser.urlbar.formatting.enabled

and unenable it.

Yes, annoyed. Even more annoying, when I just now changed the setting, before I got past the about:config screen, I got a “warning” from Firefox that changing my settings “might void my warranty”. Which is funny since the terms for Firefox require me to accept the browser “as is” and disclaims all warranties.

That’s the point.

The warning is designed as a cute/humorous/tongue-in-cheek way to slow down potentially gullible users.

If a web site tells you to do something and you start doing it, and then get this prompt, you might think for a moment before continuing. If you stop, think, and actually stop, then it did its job.

For a while there were pages that told users to copy code into the url bar or into the inspector.

I’m all for a “speed bump” approach. However, warning a civilian that their “warranty could be voided” is likely to stop at least a good portion of them from proceeding to fix the puny code tick box. The average user doesn’t read T&Cs, or if they do, they certainly have stopped by the time they get to the warranty section.

So, to be an effective speed bump, I’d much rather see something that would slow a person down but is not likely to entirely dissuade them from proceeding.

Not sure what that is at the moment, but I can tell you what it shouldn’t be — a threat to void a warranty which will scare off the average Joe and Jane from fixing something which ought to be fixed.

As timeless said, it’s supposed to be a humorous way to remind the user to be careful in there.

The upside is once you tick (or untick?*) the “don’t warn me again” box, it will stay that way.

The seemingly daily Mozilla ‘updates’ do not reset it.

(*I’ve used the same profile since Netscape morphed into Mozilla, so I haven’t seen the warning in a loooong time)

How should we deal with this now? Can anyone provide some information? How can we differentiate between legitimate and illegitimate?

Hi Rob the answer to your question is yes I have devised the programming routines that allow a user to know if the resource they are accessing is a valid resource and safe to use.

The Paypal Facebook and Bibox phishing examples in this article are the types of attacks that the system I have developed protects against that I have been writing to this forum about for 10 years now. (I am if nothing else a loyal reader of Krebs). See http://www.armorlog.com for details and https://safetrade.market for a production site example. Each user needs to have a logon that is unique to them that is not in the public domain to protect them. This prevents users from being tricked by spoofed credentials calls and allows transactions to be validated across wide area networks. It is good Krebs is yet again highlighting this issue because according to Australian Privacy Commission research something like 80% of breaches involve the theft of credentials and of that nearly 60% is from phishing attacks like the examples Krebs has highlighted in yet another fine article.

No surprises here – It was clear just this type of thing would happen.

The security zealots at Google have a lot to answer for with their attitude to HTTPS. They just didn’t about the consequences (much like our politicians!).

Of course having HTTPS doesn’t guarantee anything – but we are dealing with the public – and that’s exactly what it means 0 secure – its a padlock!

I use the IDN Safe browser extension with Firefox, Google Chrome and Opera web browsers available from Firefox Addons and Chrome Webstore.

IDN Safe displays unambiguous warnings.

The problem with browser extensions is that many have relatively unknown authors who develop something on a lark and then fail to update. Others may not do what is claimed. They’re also targets for hacks.

KOS covered this recently: https://krebsonsecurity.com/2018/09/browser-extensions-are-they-worth-the-risk/

I use the IDN Safe browser extension with Firefox, Googel Chrome and Opera.

Been using the internet since 1995. Been shopping on eBay for longer than I can remember. Was involved in web design over 10 years ago. I still script occasionally. Never heard of “look for the lock”. Ahem. =)

The ultimate anti-phishing tool is Inky Phish Fence (www.inky.com). Inky analyzes images like a human (using AI) and underlying email code like a machine. The image analysis may indicate that the sender is trying to be American Express, but the machine sees that the URL goes off to some hijacked Google domain. Even though the Google domain is legit, it doesn’t match any actual American Express domain, and is therefore flagged. The Inky gateway sits in the network and places banners (grey for OK; orange for warning; red for sure-fire phishing attempt) in the recipients’ emails. It also quarantines the links so you can look at the offending page via preview without having to actually go there.

FWTMBW, I did the config / punycode thing with my most-up-to-date Firefox (ver. 63.0.3, macOS 10.14.1) ) and found the appropriate parameter already set to “true”.

It also showed status “modified”, but I hadn’t modified it at any time previously.

That would make an interesting feature on Krebs: “Guess the Phishing site”. A series of screencaps of phishing sites, and you have to spot the tell.

Brian did something like that in this article.

https://krebsonsecurity.com/2018/03/look-alike-domains-and-visual-confusion/

The most useless investment in cybersecurity is that awareness and education can have an impact in preventing cyber attacks, of which 9 in 10 begin with phishing. Users are consistently able to correctly identify only 1 in 10 phish properly.

Isn’t it time we move to more accountable and effective solutions.

I think user education is a losing battle when ‘legit’ things like ‘Verified by Visa’ look so much like phishing attempts (redirects to some arcot.com url with you bank logo in the corner)

Seriously have a look at the screenshot here and see if you’d enter your credit card information (and more) https://www.anz.co.nz/banking-with-anz/banking-safely/verified-by-visa/

As SkunkWerks pointed out, the novice browser user is quite oblivious to symbolic ‘clues’ in the URL bar. These ‘perpetual beginners’ require a much more forceful warning system against malware websites.

I’ve found that the free version of McAfee WebAdvisor provides such air robust warning system for my elderly friends, who click on phishing email links with clueless abandon.

McAfee has separated the WebAdvisor feature from their more complete product suites, and has made it a free standalone install here:

https://www.mcafee.com/consumer/en-in/store/m0/catalog/mwad_528/mcafee-web-advisor.html

I think McAfee should be commended for providing strong coverage for multiple browsers against these malware websites, in a manner that actually makes the novice browser user stop and think, before their next click.