Researchers in the United Kingdom say they’ve discovered mounting evidence that thieves have been quietly exploiting design flaws in a security system widely used in Europe to prevent credit and debit card fraud at cash machines and point-of-sale devices.

At issue is an anti-fraud system called EMV (short for Europay, MasterCard and Visa), more commonly known as “chip-and-PIN.” Most European banks have EMV-enabled cards, which include a secret algorithm embedded in a chip that encodes the card data, making it more difficult for fraudsters to clone the cards for use at EMV-compliant terminals. Chip-and-PIN is not yet widely supported in the United States, but the major card brands are pushing banks and ATM makers to support the technology within the next two to three years.

EMV standards call for cards to be authenticated to a payment terminal or ATM by computing several bits of information, including the charge or withdrawal amount, the date, and a so-called “unpredictable number”. But researchers from the computer laboratory at Cambridge University say they discovered that some payment terminals and ATMs rely on little more than simple counters, or incrementing numbers that are quite predictable.

“The current problem is that instead of having the random number generated by the bank, it’s generated by the merchant terminal,” said Ross Anderson, professor of security engineering at Cambridge, and an author of a paper being released this week titled, “Chip and Skim: Cloning EMV cards with the Pre-Play Attack.”

Anderson said that the failure to specify that merchant terminals should insist on truly *random* numbers, instead of merely non-repeating numbers — is at the crux of the problem.

“This leads to two potential failures: If the merchant terminal doesn’t a generate random number, you’re stuffed,” he said in an interview. “And the second is if there is some wicked interception device between the merchant terminal and the bank, such as malware on the merchant’s server, then you’re also stuffed.”

The “pre-play” aspect of the attack mentioned in the title of their paper refers to the ability to predict the unpredictable number, which theoretically allows an attacker to record everything from the card transaction and to play it back and impersonate the card in additional transactions at a future date and location.

Anderson and a team of other researchers at Cambridge launched their research more than nine months ago, when they first began hearing from European bank card users who said they’d been victimized by fraud — even though they had not shared their PIN with anyone. The victims’ banks refused to reimburse the losses, arguing that the EMV technology made the claimed fraud impossible. But the researchers suspected that fraudsters had discovered a method of predicting the supposedly unpredictable number implementation used by specific point-of-sale devices or ATMs models.

For example, the team heard from a physics professor in Stockholm who went to Brussels and bought a meal at a nice restaurant for 255 euros, and immediately after midnight that evening had his card debited with two transactions of 750 euros each at another payment terminal nearby.

Anderson said the team had “lots and lots of victims” coming to them (several others are mentioned in the group’s blog post on this paper), complaining of being ripped off and then denied help from their banks. The researchers say they notified the appropriate banking industry organizations of their findings in early 2012, but opted to publish their work because it they believe it helps to explain good portion of the unsolved phantom withdrawal cases reported to them for which they previously had no explanation.

“The point here is that when a bank turns down a customer because [a fraudulent transaction] looks like cloning and cloning isn’t possible because the card has a tamper resistant chip, we show that this kind of logic doesn’t stand up,” Anderson said.

The research team said their work is informed by data collected from more than 1,000 transactions at more than 20 ATMs and a number of point-of-sale terminals. They also purchased three EMV-enabled ATMs off of eBay, and began systematically harvesting unpredictable numbers from them in hopes of finding predictable random number generators. Their research on this front is ongoing, but so far the group says it has established non-uniformity of unpredictable numbers in half of the ATMs they looked at.

In response to inquiries from the BBC, a spokeswoman for the UK’s Financial Fraud Action group downplayed the threat, telling the publication: “We’ve never claimed that chip and pin is 100% secure and the industry has successfully adopted a multi-layered approach to detecting any newly-identified types of fraud. What we know is that there is absolutely no evidence of this complicated fraud being undertaken in the real world. It requires considerable effort to set up and involves a series of co-ordinated activities, each of which carries a certain risk of detection and failure for the fraudster.”

Anderson says the industry’s response is typical.

“They’re saying this is too complex a fraud for the average villain to conduct, but they always say that, and they said that about our PIN entry device compromise research in 2008, despite the fact that it was already happening in the field. The second thing they’re saying is they have no evidence of real cases. And that’s exactly what they said in 2010, when we released our no-PIN fraud research. But we later learned that the UK cards association did at the time know that there were no-PIN frauds going on in France to the tune of about a million euros. Then when we went back and said, ‘Aha, we’ve got them for making false statements,’ it turned out that they’d written their statement very carefully to say they had no evidence of this happening in Britain, not no evidence of this happening full-stop. So this is following an established pattern by bank PR people of carefully denying it in ways that don’t stand up.”

A copy of the research paper is available here (PDF).

Great article Brian!

wow, did not know chip and pin is reliant on merchant security settings as well. Talk about a big gaping hole… What kind of variation is there in the implementation by the merchants? Is it just 3rd party or do the banks’ atms themselves have issues with the non-random number usage?

Banks in Europe pushed hard for EMV to reduce fraud. They also pushed for changes to liability laws so that transactions with PIN are presumed authentic. The onus is on the customer to prove fraud.

So they don’t need anti-fraud departments – it’s the customer’s problem now.

That is why we must be very careful in the U.S. that the banks are not able to shift the liability to customers. After all, they control the standards and the technology so they should accept the risk. Moving to the customer, as happened in Europe, would be that we would get zero help to fight fraud.

I can’t agree with you more. The chip&pin EVM cards has always been credited as being safe, but safe to whom? The banks say; ‘well, you used your pin, if it wasn’t you- you must have given your card & pin to the user’ and the merchant says ‘the buyer used a card and pin, so I’m not responsible’. So both of them are safe, but the consumer might be SOL.

There’s also the issue of how the info is saved, by whom and how long. A consumer can’t choose the back office business with access to their info, the best they can do is choose where to use their card.

I could have guessed this would be the result of a proprietary scheme relying on “secret algorithms”. Such specifications should be released and reviewed by the wider security community well in advance of their actual implementation, especially if explicitly endorsed by statutory law.

Chip-&-Pin = FAIL!

How long have we been saying that?

I think it is going to take more than EMV tricks to fix this tech. When the criminals meet a wall, they just go around it. Maybe they read Sun Tzu – a great military strategist.

I think the KISS principle is superior to this, and less tragically expensive.

I guess we should go back to a barter system then with no money at all …

Thanks Stefan; humor noted! 🙂

I wished I had the time to list all the links to attack methods used by criminals to bypass Chip-&-Pin! One of them was a simple paper clip! I can’t remember the details though!

As I’ve said on many fora before – I still say the vastly cheaper combo of MagnePrint and PassWindow, and vastly superior in second factor security too! I have no affiliation with these companies – BTW.

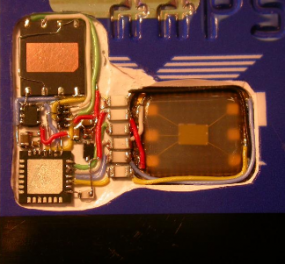

It seems that the lable of the picture (“The innards of a chip-and-PIN enabled card.”) is not correct:

from the research paper:

“Figure 3: Passive monitoring card containing real EMV chip, with monitoring microcontroller

and flash storage”

Those things are mounted on top of a card not inside.

Actually they have to carve the card out to put the electronics in (as much as possible) so that it can still be inserted in ATM slots (most ATMs will swallow the card completely, unlike store payment pads).

Brian, I think you should replace “EMV-enabled cards, which include a secret algorithm embedded in a chip” with “EMV-enabled cards, which include a secret key embedded in a chip”.

The EMV protocol (the part using PIN verification with transaction authentication to the issuer) is almost sound. It it too bad that instead of obtaining the nonce (challenge or unique number) from the issuer it gets generated by the payment terminal. There lies the problem uncovered by the papder. If EMV had designed the protocol so that the nonce is provided by the issuer and encrypted with the card key (and thus can not be tempered by the terminal) they would have severly limited posibilities of terminal attacks such as this one.

Also keep in mind that the card is actually not cloned. Transactions are pre-computed for a given card (pre-play) so that they can be played subsequently, for a given amount, country and date. Pre-computation requires the card to be present in a hacked terminal. So security of chip & PIN with current protocol is still much better than chipless cards.

Now the biggest problem for us consumers is that the liability shift operated by the banks when introducing chip & PIN (blame the merchant for PINless, blame the consumer when PIN is used) puts us at a disadvantage. Let’s hope that publicized flaws like this allow consumers to better dispute fraudulent charges.

“Now the biggest problem for us consumers is that the liability shift operated by the banks when introducing chip & PIN (blame the merchant for PINless, blame the consumer when PIN is used) puts us at a disadvantage. ”

It’s ironic when you think about it. The top card security goal of users is to keep from loosing their money due to fraud. Both the magstripe & EMV methods provide a solution to that: magstripe fraud is dealt with quickly and reimbursed by a good bank; EMV tries to prevent it, but no reimbursal. Attackers can defeat both magstripe and EMV. Hence, choosing between the two, the best way to achieve the primary security goal is (for now) to use magstripes, keep a backup card(s), & use the legal approach of banks covering losses for free.

Surprises some readers of my comment, no doubt, as I’ve posted many secure transaction schemes online in the past. However, the banks are scheming harder than ever to push merchants into adopting an insecure solution & dodging liability for their own failure to get the job done. I’ve successfully dodged the damages of credit card fraud at least once, pushing them on the bank, using the strategy I mention above. That WORKS, but EMV might not. Easy choice between the two. 😉

Good stuff, cant help thinking the researchers performed tests on devices containing old operating systems which would have been upgraded by now….?

Nice report.

This system seems to depend not just on whether a bank has maintained the security of its own ATMs, but whether anyone else is operating a compromised ATM? The banks being asked to eat the losses aren’t necessarily the ones who are responsible for the lax security, nor even in the same country? That’s going to be hard to solve.

Selling the terminals on eBay looks like a weak spot, too. It’s too easy for compromised machines to be introduced that way.

“The victims’ banks refused to reimburse the losses, arguing that the EMV technology made the claimed fraud impossible.”

Wow, this works just like “gun control” — doesn’t stop the criminals in the least, but strips all hope of defense from the innocent victims.