A steady stream of card breaches at retailers, restaurants and hotels has flooded underground markets with a historic glut of stolen debit and credit card data. Today there are at least hundreds of sites online selling stolen account data, yet only a handful of them actively court bulk buyers and organized crime rings. Faced with a buyer’s market, these elite shops set themselves apart by focusing on loyalty programs, frequent-buyer discounts, money-back guarantees and just plain old good customer service.

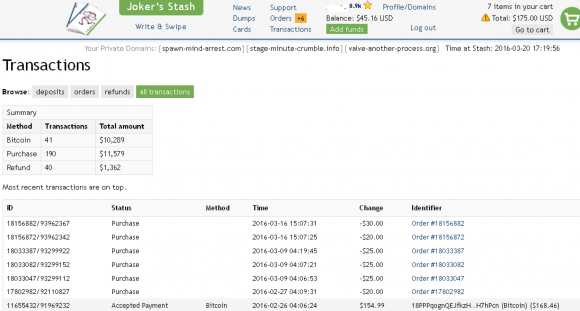

An ad for new stolen cards on Joker’s Stash.

Today’s post examines the complex networking and marketing apparatus behind “Joker’s Stash,” a sprawling virtual hub of stolen card data that has served as the distribution point for accounts compromised in many of the retail card breaches first disclosed by KrebsOnSecurity over the past two years, including Hilton Hotels and Bebe Stores.

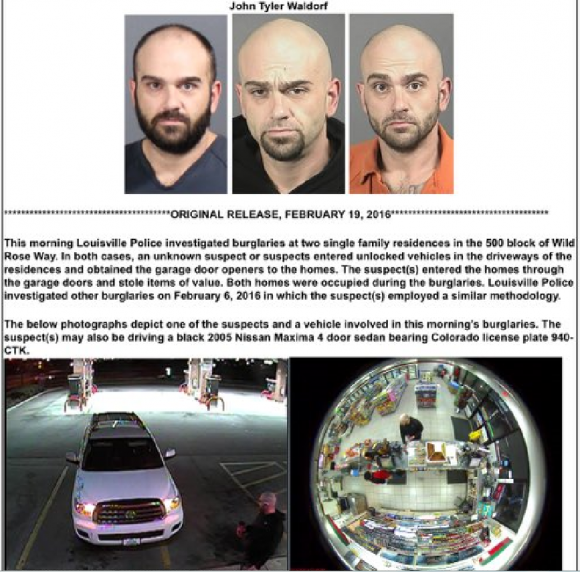

Since opening for business in early October 2014, Joker’s Stash has attracted dozens of customers who’ve spent five- and six-figures at the carding store. All customers are buying card data that will be turned into counterfeit cards and used to fraudulently purchase gift cards, electronics and other goods at big-box retailers like Target and Wal-Mart.

Unlike so many carding sites that mainly resell cards stolen by other hackers, Joker’s Stash claims that all of its cards are “exclusive, self-hacked dumps.”

“This mean – in our shop you can buy only our own stuff, and our stuff you can buy only in our shop – nowhere else,” Joker’s Stash explained on an introductory post on a carding forum in October 2014.

“Just don’t wanna provide the name of victim right here, and bro, this is only the begin[ning], we already made several other big breaches – a lot of stuff is coming, stay tuned, check the news!” the Joker went on, in response to established forum members who were hazing the new guy. He continued:

“I promise u – in few days u will completely change your mind and will buy only from me. I will add another one absolute virgin fresh new zero-day db with 100%+1 valid rate. Read latest news on http://krebsonsecurity.com/ – this new huge base will be available in few days only at Joker’s Stash.”

As a business, Joker’s Stash made good on its promise. It’s now one of the most bustling carding stores on the Internet, often adding hundreds of thousands of freshly stolen cards for sale each week.

A true offshore pirate’s haven, its home base is a domain name ending in “.sh” Dot-sh is the country code top level domain (ccTLD) assigned to the tiny volcanic, tropical island of Saint Helena, but anyone can register a domain ending in dot-sh. St. Helena is on Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) — the same time zone used by this carding Web site. However, it’s highly unlikely that any part of this fraud operation is in Saint Helena, a remote British territory in the South Atlantic Ocean that has a population of just over 4,000 inhabitants.

This fraud shop includes a built-in discount system for larger orders: 5 percent for customers who spend between $300-$500; 15 percent off for fraudsters spending between $1,000 and $2,500; and 30 percent off for customers who top up their bitcoin balances to the equivalent of $10,000 or more.

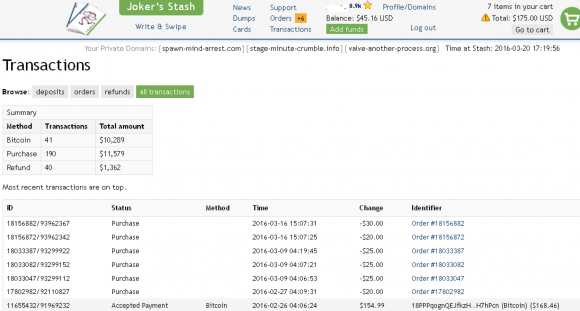

For its big-spender “partner” clients, Joker’s Stash assigns three custom domain names to each partner. After those partners log in, the different 3-word domains are displayed at the top of their site dashboard, and the user is encouraged to use only those three custom domains to access the carding shop in the future (see screenshot below). More on these three domains in a moment.

The dashboard for a Joker’s Stash customer who has spent over $10,000 buying stolen credit cards from the site. Click image to enlarge.

REFUNDS AND CUSTOMER LOYALTY BONUSES

Customers pay for stolen cards using Bitcoin, a virtual currency. All sales are final, although some batches of stolen cards for sale at Joker’s Stash come with a replacement policy — a short window of time from minutes to a few hours, generally — in which buyers can request replacement cards for any that come back as declined during that replacement timeframe.

Like many other carding shops, Joker’s Stash also offers an a-la-carte card-checking option that customers can use an insurance policy when purchasing stolen cards. Such checking services usually rely on multiple legitimate, compromised credit card merchant accounts that can be used to round-robin process a small charge against each card the customer wishes to purchase to test whether the card is still valid. Customers receive an automatic credit to their shopping cart balances for any purchased cards that come back as declined when run through the site’s checking service.

This carding site also employs a unique rating system for clients, supposedly to prevent abuse of the service and to provide what the proprietors of this store call “a loyalty program for honest partners with proven partner’s record.” Continue reading →

Earlier this week, a prominent member of a closely guarded underground cybercrime forum posted a new thread advertising the sale of a database containing the contact information on some 1.5 million customers of Verizon Enterprise.

Earlier this week, a prominent member of a closely guarded underground cybercrime forum posted a new thread advertising the sale of a database containing the contact information on some 1.5 million customers of Verizon Enterprise.

Most states didn’t start processing returns until after March 1, which is exactly when a flood of data breaches related to phished employee W2 data began washing up. As KrebsOnSecurity

Most states didn’t start processing returns until after March 1, which is exactly when a flood of data breaches related to phished employee W2 data began washing up. As KrebsOnSecurity

Spam purveyors are taking advantage of so-called “

Spam purveyors are taking advantage of so-called “ Seattle-based Moneytree sent an email to employees on March 4 stating that “one of our team members fell victim to a phishing scam and revealed payroll information to an external source.”

Seattle-based Moneytree sent an email to employees on March 4 stating that “one of our team members fell victim to a phishing scam and revealed payroll information to an external source.”

The bulk of the security holes plugged in this month’s Patch Tuesday reside in either Internet Explorer or in Microsoft’s flagship browser — Edge. As security firm Shavlik

The bulk of the security holes plugged in this month’s Patch Tuesday reside in either Internet Explorer or in Microsoft’s flagship browser — Edge. As security firm Shavlik