As a rule, I tend to avoid writing about reports and studies unless they offer truly valuable and actionable insights: Too often, reports have preconceived findings that merely serve to increase hype and drum up business for the companies that commission them. But I always make an exception for the annual data breach report issued by the Verizon Business RISK team, which is consistently so chock full of hype-slaying useful data and conclusions that it is often hard to know what not to write about from its contents.

Once again, some of the best stuff is buried deep in this year’s report and is likely to be missed in the mainstream coverage. But let’s get the headline-grabbing findings out of the way first:

-Verizon’s report on 2009 breaches for the first time includes data from the U.S. Secret Service. Yet, the report tracks a sharp decline in the total number of compromised records (143 million compromised records vs. 285 million in 2008).

-Verizon’s report on 2009 breaches for the first time includes data from the U.S. Secret Service. Yet, the report tracks a sharp decline in the total number of compromised records (143 million compromised records vs. 285 million in 2008).

-85 percent of records last year were compromised by organized criminal groups (this is virtually unchanged from the previous report).

-94 percent of compromised records were the result of breaches at companies in the financial services industry.

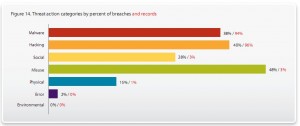

-45 percent of breaches were from external sources only, while 27 percent were solely perpetrated from the inside by trusted employees.

Among the most counter-intuitive findings in the report?

There wasn’t a single confirmed intrusion that exploited a patchable vulnerability. Rather, 85 percent of the breaches involved common configuration errors or weaknesses that led to things like SQL database injection attacks, and did not require the exploitation of a flaw that could be fixed with a software patch. In most cases, the breaches were caused by weaknesses that could be picked up by a free Web vulnerability scanner:

“Organizations exert a great deal of effort around the testing and deployment of patches — and well they should. Vulnerability management is a critical aspect of any security program. However, based on evidence collected over the last six years, we have to wonder if we’re going about it in the most efficient and effective manner. Many organizations treat patching as if it were all they had to do to be secure. We’ve observed multiple companies that were hell-bent on getting patch X deployed by week’s end but hadn’t even glanced at their log files in months.”

Speaking of log files, one of the most interesting sections of the 66-page report comes in a sidebar titled “Of Needles and Haystacks,” which states that 86 percent of all breaches last year could have been prevented if victim companies had simply looked for unusual patterns in the log files created by their Web servers.

“In 86 percent of these breaches, the victim didn’t need forensic tools or fancy intrusion detection devices to figure out what happened, because they could read the entire event out of their logs,” said Bryan Sartin, one of the multiple authors of the Verizon report. “Forensic tools are great for recreating events that aren’t logged, but in most of the cases last year, the data was all there, they just weren’t looking at it.”

Sartin said a common complaint he hears about log files is that they are generally so huge that trying to find signs that someone has broken in by looking at your logs is akin to finding a needle in a haystack. But Sartin notes that — viewed another way — the reality is quite the opposite.

“If you take a 500 gigabyte log of a Web server and scroll down through it real fast, you’re going to see a pattern of the same old request over and over again. Suddenly, you hit one that’s formatted completely differently, and instead of being 3 lines it’s 33 lines long and it contains data that’s going the other way in the form of error codes. So these are extremely obvious and noisy attacks that you could mitigate simply by looking for them. But for some reason, many organizations still think they have to go out and buy intrusion-detection devices and more things that produce logs, when their underlying problem was that they weren’t looking effectively at the logs in the first place, and now they’ve just made the problem worse.”

A key finding in this year’s report is that most companies suffering breaches missed obvious signs of employee misconduct – breaches that were either initiated or aided by employees. Sartin said in almost every case where a breach investigation zeroed in on an employee as the culprit, investigators found ample evidence that the employee had long been flouting the company’s computer security and acceptable use policies that prohibit certain behaviors, such as surfing porn or gambling Web sites on company time and/or on corporate-issued laptops.

The study found a strong correlation between ‘minor’ policy violations and more serious abuse. From the report: “Based on case data, the presence of illegal content, such as pornography, on user systems (or other inappropriate behavior) is a reasonable indicator of a future breach. Actively searching for such violations rather than just handling them as they pop up may prove even more effective.”

The Verizon study also takes aim at the hype surrounding the “advanced persistent threat,” or APT — a politically and emotionally charged term that has become virtually synonymous with the term “cyber war”. The concept of APT — which describes attackers who are motivated, skilled, well-funded and patiently directed at compromising a specific target — is not new, but it came into vogue earlier this year with Google’s public disclosure that its intellectual property had been stolen in a targeted attack originating from China.

“Maybe 28 times just in the U.S. alone last year — we had some company in the oil and gas or other critical infrastructure industry come to us…[having found] the most rudimentary, nonthreatening virus on their Web server and instantly jumping to the conclusion that some government behind a certain Asian country was hacking into their company to steal their resources,” Sartin said. “And more often than not, we were being brought in to prove that it didn’t happen, when it turns out they were sounding the alarm for all the wrong reasons. We called it out in the report and said, ‘Hey guys, thanks for the business, but don’t believe the hype.'”

Anyone seriously interested in understanding what APT is — and more importantly isn’t — should read the July cover story of Information Security Magazine, a thoughtful and incisive analysis by blogger Richard Bejtlich.

Another gem in the report is an appendix compiled by the Secret Service that includes a tale about how one of the most notorious cyber thieves ever arrested was lured to a meeting in Turkey in 2007 where he was arrested by local authorities. Wired.com’s Kim Zetter delves into this revelation in more detail here.

The full Verizon breach report is available from this link (PDF).

This is interesting information. When you mentioned that none of the attacks were against patchable exploits I had two thoughts. First, that means companies are keeping up with patches and second I hope management does not start to think that patching is no longer needed.

Keep up the good work!

Hi there!

Love your blog!!!! The Verizon Breach report that I got from you site has a problem with it. I seems to choke or have a problem somewhere early in the document. I too look forward to reading this document every year. I only wish more of my Info Sec colleagues would read it to get a better understanding of the current threat.

Paul, I’m sorry you’re having problems. I’m going to guess you’re using…..Chome? Am I right? I’ve heard the same report from other Chrome users. Unfortunately, I don’t know what the answer is.

Very interesting. I am curious what correlations exist between insider/outsider breaches and the types of information stolen. For instance, I have heard that credit card thefts are primarily insider jobs but have no idea if that’s so.

@Steve –

We’ll be doing some slicing of the data like this over the next few months. I’ll be sure to add this one to the list.

Oh how I wish there was more information on these breaches. Especially the ones from Australia. I would like to know if I am in the database of some organised crime gang! But keeping the customers in the dark is good for business.

It appears from the report that the number of breaches involving insiders is significantly increasing which is of great concern. Perhaps this is a result of more effective policies on the public side resulting in criminals resorting to gaining assistance from insiders to perpetrate frauds. This indicates the need for more effective systems to be in place to prevent manipulation of access rights. This is evidenced by the correlation in the increase in privileges misuse noted in the report.

Louis — The top of the report delves into some possible explanations for the apparent increase in insider cases.

My sense is — and this is called out there — that the most likely explanation is the addition of the Secret Service caseload, as a disproportionate number of their cases involve insiders (cases where the victim company feels confident they know who the culprit employee is, they tend to go straight to contacting law enforcement).

Thanks for that, it will be interesting to see the figures next year. I am interested to see if they correlate with general fraud statistics which in Australian are around the 57% internal excluding the financial sector which has much higher rate of around 84% external (down from 90% in 2006). (Stats courtesy KPMG Australia Fraud Survey 2009).

You’re on El Reg http://www.theregister.co.uk/2010/07/28/scareware_chargebacks_rare/

A little OT, but sweet nonetheless 🙂 Thanks for the heads up, I had hadn’t seen that.

I have a bit of mixed feelings versus Sartin suggestion of going really fast through 500GB log files looking for changes in patterns. I do it as well (though generally not when searching security related logs) and is quite effective and a vast improvement over not looking at all at logs. Yet, is quite subjective and I noticed individual members’ of an admin team ability to spot changes in log patterns vary greatly and I think is just not enough a company should put in place to detect security breaches. “Complex” intrusion detection system might or might not be the answer either, I found the most effective way for an organization is to build own set of automated scripts, fully tailored, which automatically mask normal patterns and extracts area of interests from the logs for human deeper investigation.

This is great addition information you have addes to this story, I got a lighter less detailed version on anthoter tech site, I wonder thou Brian if this fellow has been doing freelance coding for other crime ware kits or on a per contract basis for other bot nets, I see some similarities in some of the Newer Zeus modules with a some what similar encrypted communications protocol, makes me wwonde rif there isn’t a coreelation..I hoe you keep uus updated as to any fruther developments Brian, I think there is a lot of good OSINT that could be gleaned from this.

Thanks, David. I’m moving your comment over to the Mariposa botnet author story where I think this belongs 🙂

Once again, my valuable time has been rewarded.

Most often than not, I browse the subject lines and end up reading your articles.

I too saw the Verizon report coming out and ignored it for the very reasons you mentioned in the beginning.

Your articles both enlightened me to the fact I should check it out and provided valuable analysis I was able to forward directly to colleagues whose immediate response was “Wow, thanks”…

Keep it up

One piece of information I was not sure if I misunderstood was in regards to their PCI findings… 79% of those breached were not compliant at their last assessment or never assessed – while 21% had been found compliant in their assessment (this isn’t to say they were compliant at time of breach – simply that they had passed their annual assessment). Out of that 21% apparently all but one of them were level 1 merchants. Now here’s where I’m not sure I’m understanding correctly – is this saying that the majority of other levels are breached because they do not take the time to be compliant while level one merchants (even if validated at a point in time) are higher targets and so the theives don’t mind spending more time getting through their security? And that perhaps the other levels are more of the opportunistic breaches vs targeted? And if that’s true, statistically speaking then, being compliant actually would take most other merchants out of the attack range wouldn’t it?

@T.Anne –

We included the bit about the non-compliant orgs being mostly level 1 to rule out the possibility of them being compliant through a self-assessment questionnaire. IOW, because they were L1 and therefore were validated through a QSA, the result is more interesting. We weren’t intending to suggest any correlation between merchant size and the likelihood of a breach or security posture.

I would say that, in general, lower merchant levels draw more opportunistic attacks (often related to POS configuration) while the bigger merchants and especially processors are more targeted.

“The study found a strong correlation between ‘minor’ policy violations and more serious abuse.”

I would just like to point out the similarity to that quote and the “Broken Window” theory cited as a factor in reducing crime in New York city. See wikipedia’s entry for that term for an introduction.