There are still many unanswered questions about the recent attack on Sony Pictures Entertainment, such as how the attackers broke in, how long they were inside Sony’s network, whether they had inside help, and how the attackers managed to steal terabytes of data without notice. To date, a sizable number of readers remain unconvinced about the one conclusion that many security experts and the U.S. government now agree upon: That North Korea was to blame. This post examines some compelling evidence from past such attacks that has helped inform that conclusion.

The last time the world saw an attack like the one that slammed SPE was on March 20, 2013, when computer networks running three major South Korean banks and two of the country’s largest television broadcasters were hit with crippling attacks that knocked them offline and left many South Koreans unable to withdraw money from ATMs. The attacks came as American and South Korean military forces were conducting joint exercises in the Korean Peninsula.

That attack relied in part on malware dubbed “Dark Seoul,” which was designed to overwrite the initial sections of an infected computer’s hard drive. The data wiping component used in the attack overwrote information on infected hard drives by repeating the words “hastati” or “principes,” depending on which version of the wiper malware was uploaded to the compromised host.

Both of those terms reference the military classes of ancient Rome: “hastati” were the younger, poorer soldiers typically on the front lines; the “principes” referred to more hardened, seasoned soldiers. According to a detailed white paper from McAfee, the attackers left a calling card a day after the attacks in the form of a web pop-up message claiming that the NewRomanic Cyber Army Team was responsible and had leaked private information from several banks and media companies and destroyed data on a large number of machines.

The message read:

“Hi, Dear Friends, We are very happy to inform you the following news. We, NewRomanic Cyber Army Team, verified our #OPFuckKorea2003. We have now a great deal of personal information in our hands. Those includes; 2.49M of [redacted by Mcafee] member table data, cms_info more than 50M from [redacted]. Much information from [redacted] Bank. We destroyed more than 0.18M of PCs. Many auth Hope you are lucky. 11th, 12th, 13th, 21st, 23rd and 27th HASTATI Detachment. Part of PRINCIPES Elements. p.s For more information, please visit www.dropbox.com login with joseph.r.ulatoski@gmail.com::lqaz@WSX3edc$RFV. Please also visit pastebin.com.”

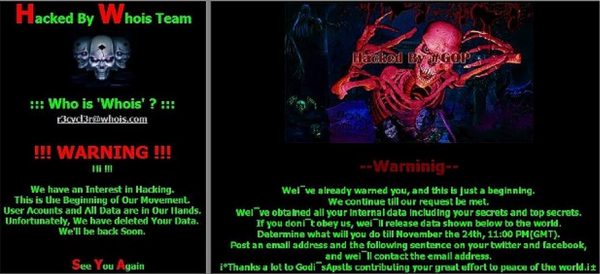

The McAfee report, and a similarly in-depth report from HP Security, mentions that another group calling itself the Whois Team — which defaced a South Korean network provider during the attack — also took responsibility for the destructive Dark Seoul attacks in 2013. But both companies say they believe the NewRomanic Cyber Army Team and the Whois Team are essentially the same group. As Russian security firm Kaspersky notes, the images used by the WhoisTeam and the warning messages left for Sony are remarkably similar:

The defacement message left by the Whois Team in the 2013 Dark Seoul attacks (left) and the message left for Sony (right).

Interestingly, the attacks on Sony also were preceded by the theft of data that was later leaked on Pastebin and via Dropbox. But how long were the attackers in the Sony case inside Sony’s network before they began wiping drives? And how did they move tens of terabytes of data off of Sony’s network without notice? Those questions remain unanswered, but the McAfee paper holds a few possible clues.

A LENGTHY CAMPAIGN

McAfee posits that, based on the compile times of the backdoor malware used to upload the drive-wiping malware, the targets in the Dark Seoul attacks were likely compromised by a remote-access Trojan delivered by a spear-phishing campaign at least two months before the data destruction began. More importantly, McAfee concludes that the data-wiping and backdoor malware used in the Dark Seoul attack was but a small component of an elaborate cyber-espionage campaign that started in 2009 and targeted only South Korean assets.

“McAfee Labs has uncovered a sophisticated military spying network targeting South Korea that has been in operation since 2009. Our analysis shows this network is connected to the Dark Seoul incident. Furthermore, we have also determined that a single group has been behind a series of threats targeting South Korea since October 2009. In this case the adversary had designed a sophisticated encrypted network designed to gather intelligence on military networks.

We have confirmed cases of Trojans operating through these networks in 2009, 2010, 2011, and 2013. This network was designed to camouflage all communications between the infected systems and the control servers via the Microsoft Cryptography API using RSA 128-bit encryption. Everything extracted from these military networks would be transmitted over this encrypted network once the malware identified interesting information. What makes this case particularly interesting is the use of automated reconnaissance tools to identify what specific military information internal systems contained before the attackers tried to grab any of the files.”

The espionage malware was looking for files that contained specific terms that might indicate they harbored information about U.S. and Korean military cooperation, including “U.S. Army” and “Operation Key Resolve,” an annual military exercise held by U.S. forces and the South Korean military.

The Dark Seoul attacks were hardly an isolated incident. In 2011, the same Korean bank that was attacked in the 2013 incident was also hit with denial-of-service attacks and destructive malware. On July 4, 2009, a wave of denial-of-service attacks washed over more than two dozen Korean and U.S. Government Web sites, including the White House and the Pentagon. July 4 is Independence Day in the United States, but it also happened to be the very day that North Korea launched seven short-range missiles into the Sea of Japan in a show of military might. By the time the third wave of that attack subsided on July 9, the assailants had pushed malware to tens of thousands of zombie computers used in the assault that wiped all data from the machines.

The co-founder of CrowdStrike, a security firm that focuses heavily on identifying attribution and actors behind major cybercrime attacks, said his firm has a “very high degree of confidence that the FBI is correct in” attributing the attack against Sony Pictures to North Korean hackers, and that CrowdStrike came to this conclusion independently long before the FBI came out with its announcement last week.

“We have a high-confidence that this is a North Korean operator based on the profiles seen dating back to 2006, including prior espionage against the South Korean and U.S. government and military institutions,” said Dmitri Alperovitch, chief technology officer and co-founder at CrowdStrike.

“These events are all connected, through both the infrastructure overlap and the malware analysis, and they are connected to the Sony attack,” Alperovitch said. “We haven’t seen the skeptics produce any evidence that it wasn’t North Korea, because there is pretty good technical attribution here. I want to know how many other hacking groups are so interested in things like Key Resolve.”

Security firms like HP refer to the North Korean hacking team as the “Hastati” group, but CrowdStrike calls them by a different nickname: “Silent Chollima.” A Chollima is a mythical winged horse which originates from the Chinese classics.

“North Korea is one of the few countries that doesn’t have a real animal as a national animal,” Alperovitch said. “Which, I think, tells you a lot about the country itself.”

The “silent” part of the moniker is a reference to the stubborn fact that little is known about the hackers themselves. Unlike hacker groups in other countries where it is common to find miscreants with multiple profiles on social networks and hacker forums that can be used to build a more complete profile of the attackers — the North Koreans heavily restrict the use of Internet communications, even for their cyber warriors.

“First of all, they don’t have a ton of Internet infrastructure in North Korea, and they don’t have forums and social media which typically helps you identify, for example, whether an attack is from Russians or the Chinese,” Alperovitch said. “In general, the North Korean regime is one of the hardest intelligence targets for the intelligence and cyber attribution communities.”

On Monday, the folks at Dyn Research — a company that tracks Internet connectivity issues around the globe — said its sensors noted that North Korea inexplicably went offline on Monday, Dec. 22, at around 16:15 UTC (01:15 UTC Tuesday in the North Korean capital of Pyongyang). But the researchers stopped short of attributing a reason behind the outage.

“Who caused this, and how?,” wrote Jim Cowie, chief scientist at Dyn. “A long pattern of up-and-down connectivity, followed by a total outage, seems consistent with a fragile network under external attack. But it’s also consistent with more common causes, such as power problems.”

Interestingly, this pattern of downtime also was witnessed directly following the above-described 2013 attacks that targeted South Korean banks and media firms. According to Jason Lancaster, a security researcher at HP, the entire North Korean Internet space suffered a similar outage around the same time as the 2013 offensive against South Korea.

“When they came back online, one of those four [North Korean Internet address blocks] was routing through an Intelsat satellite connection,” Lancaster said. “What caused the 2013 outage? They never determined the cause. The speculation was that they were under attack, but there was never any proof of that happening.”

Additional reading:

US-CERT analysis of the computer worm used in the attack on Sony.

TaoSecurity Blog: What Does ‘Responsibility’ Mean for Attribution?

McAfee report on Dark Seoul attacks (PDF)

HP Security: Profiling an Enigma – The Mystery of North Korea’s Cyber Threat Landscape (PDF)

Read the McAfee report. Lots of insight. PRK for sure.

US-CERT and the rest of Homeland Security beg private companies to join in information sharing about Cyber attacks. They repeat quite often that when sharing the information there are a number of ways your private information will be protected from FOIA requests.

If it meets any of these exemptions – http://www.dhs.gov/foia-exemptions

Take a hard look at#4 – Exemption 4 – Protects trade secrets and commercial or financial information which could harm the competitive posture or business interests of a company.

For more in that same vein look at the Protected Critical Infrastructure Program – https://www.us-cert.gov/pcii

Also see the NIST Draft Document – Guide To Cyber Threat Information Sharing – http://csrc.nist.gov/publications/drafts/800-150/sp800_150_draft.pdf

Page 8 is relevant here.

Brian, as always, thanks for the detailed exposition.

There are indeed several similarities to past N Korea-sponsored attacks.

But I still think whoever is responsible is merely attempting to throw investigators off the scent.

In my opinion there is nothing here or anywhere else I’ve seen tending to incriminate NK that could not just as easily be deliberate attempts to conceal the true sponsors and perpetrators.

My money is still on disgruntled insiders in either or both those roles.

Politically, NK is to the Sony attack as Iraq was to 9/11/01 .

I see a lot of people still say this could be the work of an insider.

My question is what skill level would be required to pull this off? Is the bar significantly lower for an insider or does it still require a high degree of hacking skill?

Seems if the skill requirement is high, it would be pretty easy to compile a list of insiders with that knowledge and investigate them quickly enough to either charge them or move on to other suspects.

He doesn’t need any skill. all he is doing is copying files to a pc.

Even disabling autorun as a previous poster suggested is only going to stop someone doing this by accident with a planted usb or something, but not someone purposely.

I’m just wondering what people think of the following article? There is alot of evidence out there that North Korea was in fact NOT responsible. There is a lack of real evidence, all evidence is either circumstantial or follows a pattern of “if it looks like a duck…”

http://marcrogers.org/2014/12/18/why-the-sony-hack-is-unlikely-to-be-the-work-of-north-korea/

Love your website Brian, I read it daily, keep up the great work.

EDIT: Follow up to the above linked article citing more technical evidence why North Korea didn’t do it… wondering what you all think.

http://marcrogers.org/2014/12/21/why-i-still-dont-think-its-likely-that-north-korea-hacked-sony/

Great analysis. It does make you wonder. The best indication that it was not N. Korea would be that the hacker group said it was okay to release the movie. This does not sound like NK’s fearless leader.

The other element that makes finger pointing at NK suspicious is that the movie was not initially targeted, and only targeted after someone speculated that it might be the motive.

Sony is part of the US Media Oligopoly; the US government has interest in keeping them viable. It is better for the stock-holders, Employee’s, and for the Federal Government to believe this is a nation state attack by an APT and the US Government will cover any losses, rather than an attack some punk kid can think up. It costs the Secret Service and FBI exactly nothing to do a press release.

The Group that compromised and destroyed their systems and network was looking to destroy that company. They are waging a cyber-war not just against the information infrastructure of the organization, but against the personal lives of the employee’s as well. They are aiming for the long-term game, to dissuade and disparage individuals within the organization from working there, which reduces the quality of works originating there. It does not help their stocks are down quite a bit.

Maintaining Picture Perfect Opsec requires you make sure your opponent does not know the reason for the attack. Thus far, not a peep. This indicates the group is probably fighting for a higher ideal, and Sony’s corporate management is reaping a nightmare of their own sowing. Those details will never see the day of light.

>RSA 128-bit

That’s extremely weak. Is that a typo?

RSA is a public key algorithm with long keys. Given that 512 bit, 768 bit have been publicly broken and that 1024 has been deprecated by NIST. The McAfee quote “Microsoft Cryptography API using RSA 128-bit encryption.” makes no sense. It wouldn’t take that much cpu power to crack that. I doubt you could even construct a public key that short with the API. A 128 bit symmetric key would make sense. Something is missing or wrong there.

I am concerned and somewhat amused by the number of posters that seem to believe they have the need or right to view and discuss all the gathered information on the DPRK and Sony hacking intrusion along with previous computer intrusions attributed to the DPRK.

Throughout history no such right, to view or hear all of a ruling government’s secrets, has ever existed.

After reading the released information what I have discovered is that we all now have an indication of the abilities of anarchists and small governments to affect the way of life many corporations and readers here have become accustomed to. Remember all your personal or corporate books, correspondence and such should be kept in a paper files locked safely in your fire-safe safe.

Remember and heed Lomasney’s famous saying on the importance of discretion: “Never write if you can speak; never speak if you can nod; never nod if you can wink.”

Now that Sony has decided to release the movie anyway, what have the hackers said in response?

I am not an expert on anything cyber; but, I can determine that the web message left by “Whois ” was written by someone who speaks (and spells) good English— his first language! The Sony message was written by someone who speaks English as a second language. And lastly this sentence– ¡ Thanks a lot to God ¡–no card carrying North Korean would use that phrase.Their government persecutes Christians–unless they were referring to their only god Kim Jong-un.

The article and responses are all very interesting, but I am increasingly skeptical of any official determination of guilt by the US government. Since all the “facts” we have are those we are given, the veracity and provenance of those facts is paramount. And recent corporate collusion does not increase my willingness to believe what McAfee or anyone else states as the facts in the case. That leaves me in a very uncomfortable state of not knowing what the truth is or who is telling it.

Maybe. Against that, since the Snowden revelations there has been a continous churning of crises. The Russians were going to get us, then Isis, now the North Koreans. Like the others, this crisis will fizzle out and make way for the next one. The identification of North Korea as a dangerous menacing cyber attacker here is just too convenient.

Pasca, History is written by the winners.

Despite the U.S. pointing the finger at North Korea over the cyberattack and threats, some cybersecurity experts are questioning whether the communist regime was behind it.

Kurt Stammberger, a senior vice president with cybersecurity firm Norse, told CBS News that the cyberattack was an inside job.

“Sony was not just hacked, this is a company that was essentially nuked from the inside,” Stammberger told CBS News.

He added, “”We are very confident that this was not an attack master-minded by North Korea and that insiders were key to the implementation of one of the most devastating attacks in history.”

Stammberger claims data indicates that a woman who calls herself “Lena,” and is connected to the “Guardians of Peace,” might be behind the cyberattack. She allegedly worked for Sony for ten years in the company’s Los Angeles office.

“This woman was in precisely the right position and had the deep technical background she would need to locate the specific servers that were compromised,” Stammberger told CBS News.

http://atlanta.cbslocal.com/2014/12/24/sony-cyberattack-inside-job/

In this area there is usually no clear proof of who did what and the best you are going to get is informed speculation sufficient to draw a reasoned conclusion. Those that expect Kim Jong Un to declare it will never be convinced otherwise. Such is the state of these activities and North Korea’s statements of being as pure as Caesar’s wife are unconvincing.

the McAfee paper presents pretty strong evidence on linking the previous attacks, from 2009 up to and including DarkSeoul in 2013.

it doesn’t, however, present evidence for tying it to N Korea directly.

in fact, there is suspiciously little that can be lined to Korea in malware – other than in the list of interesting keywords to search for. but that can be treated as external information provided by the “customer”.

in the code itself, however, there are more traces of chinese influsence – for example, password used by the agents when joining irc is “wodepeng”[you], which translates from chinese as “my good friend” (in McAfee report the “you” part is missing but it’s likely that McAfee inadvertently truncated the password: this malware sample from 2011[1] shows “you” on the next line in hex dump of the packet, it’d be easy to miss).

“chang” and “tong” used in different places are more like chinese than korean.

i’m personally leaning towards the attack being done by Chinese. whether it was carried out in the interest of NK or as an elaborate diversion to frame NK, i don’t know but leaning towards the first. i think NK, not having infrastructure and skilled people to carry out the spying operation, just went shopping and found some chinese hackers to do it for them. hackers were obviously told to only target S.Korean websites.

[1] http://www.threatexpert.com/report.aspx?md5=39153407ac257e0ed110532b4d025866

http://goo.gl/okUwO8

seems the n.korans went to all this trouble jus tto release the movie (not)

its abviously a USA/Japan propaganda film!

Its funny 40min in but….

face it, your sony movie dream is DOA, but FOX thats another story if you get to the bottom of this!

http://www.thedailybeast.com/articles/2014/12/24/no-north-korea-didn-t-hack-sony.html

More of the pieces, should I say pc’s. You’ll know how the BATFE still takes pieces of crime scene evidence and places those pieces into so-called new cases. Felony!! They got caught.

Yeah, Greg D, that followup article sums up my thoughts (and more). I don’t see any good evidence, and the flimsy attribution leads me to more questions (I’ll elaborate on this in a bit).

I am surprised that you have written an article with this title. What is the case for this being North Korea (the government) as opposed to simply North Korean sympathizers? What is the case for these attacks being definitively linked to one another? Similarity this obvious in malware isn’t very difficult to fake. Also, what is this infrastructure overlap? The IP addresses? If one of the North Korean allocated IP addresses had been included, that would be somewhat more convincing. However, all the IP addresses are (as the previously-mentioned article states) simply easily-proxied addresses.

I understand security researchers saying “we think that the North Korean government has the highest likelihood of having performed all of these attacks”. Occam’s razor seems to imply that. But I think that it is still very very likely that it wasn’t them, because when malicious entities are performing these acts, the easiest way to cover your tracks is to lead investigators down another trail.

My biggest question, however, is about our government’s attribution of these attacks. What are the possible reasons our government would come out and say it was a specific country’s doing?

1. A country admitting it. Obviously that didn’t happen.

2. Solid, substantial evidence. This is the main point of contention, of course, but I think there is much less than a 90% chance that it was actually the government of North Korea, and probably less than 50%. It is certainly likely in these scenarios that the intent was to get blame put on the DPRK government, and the mocking of the FBI by the hackers seems to imply this.

3. Political reasons. I think this is our main motivation, and it is potentially twofold. (a) The government wanted someone to be held responsible to look like we were doing something and that we aren’t weak, that we stand up for ourselves, etc. (b) Isn’t it convenient to have someone to rally our country against when everyone has been very anti-government lately? It also provides for some nice news cycle filling. I don’t even think it’s unreasonable to suspect US initiation of the whole ordeal.

I look at it this way. Though people can speculate all they want. They can point fingers, guess, and conclude. Sure, it may have the same MO as other attacks, but if the attacker didn’t want to be identified, doing it the North Korean way would definitely have eyes on a prior suspect.

All this starts with a company that has to use a real life named leader? Commmon, as unstable as that regime seems to be, its like walking up to the biggest bear in the world and smacking it with a ball-peen hammer. Your asking for trouble.

It appears that there wasn’t even a tid bit of risk identified with this movie release? No expected fallout?

I can imagine just about every intelligence community has tidbits of information that can lead to – just about anywhere. If the software was used, tried and true at one time, and given the nod that the stuff works, then others are going to try that as well.

The basic bottom line here, to me anyways is, lack of CSO direction and vision. The CSO should have said, Whoa – you guys are using a name of an unstable leader, AND your going to say he is assassinated, by the USA? Isn’t that a bit bold ? Countries other than the USA do take offense to a USA “non-traditional” thinking.

In the past Asian based countries with fists in the sky vowed to rain nuclear weapons down upon the USA. Having a corporation of any kind stirring the bees nest is probably not the best idea in the world.

This all probably would have never been an issue – at least to this magnitude if Sony didn’t personally attack a live foreign leader.

It is extremely hard to point finger at some one based on previous MO’s. Sure, the leader is a hot-head, unhealthy, unstable and – Sure more than likely ordered an attack – but so far – no hard core evidence has been put on the table to read.

Thanks to Mr. K. for the well-written article and to those who gave this series of informed, reasonable comments.

The magazine, The Economist, comes down on the side of those who say there’s no conclusive evidence that North Korea is responsible (just in case you don’t know the magazine, the caption to the photo is ironic):

http://www.economist.com/news/united-states/21637402-america-was-too-quick-blame-north-korea-hack-attack-sony-kim-jong-un?fsrc=nlw|hig|30-12-2015|NA