Many U.S. government Web sites now carry a message prominently at the top of their home pages meant to help visitors better distinguish between official U.S. government properties and phishing pages. Unfortunately, part of that message is misleading and may help perpetuate a popular misunderstanding about Web site security and trust that phishers have been exploiting for years now.

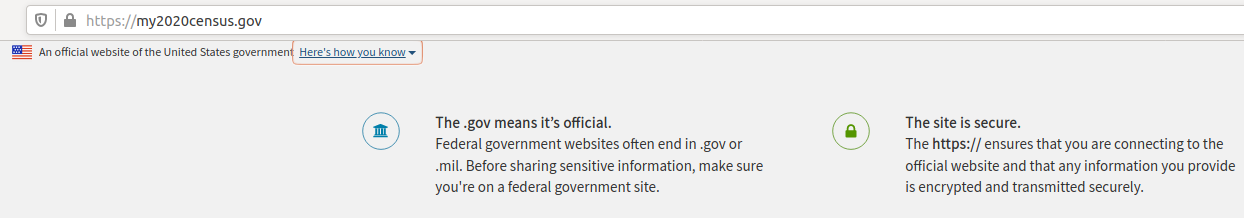

For example, the official U.S. Census Bureau website https://my2020census.gov carries a message that reads, “An official Web site of the United States government. Here’s how you know.” Clicking the last part of that statement brings up a panel with the following information:

The text I have a beef with is the bit on the right, beneath the “This site is secure” statement. Specifically, it says, “The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website….”

Here’s the deal: The https:// part of an address (also called “Secure Sockets Layer” or SSL) merely signifies the data being transmitted back and forth between your browser and the site is encrypted and cannot be read by third parties.

However, the presence of “https://” or a padlock in the browser address bar does not mean the site is legitimate, nor is it any proof the site has been security-hardened against intrusion from hackers.

In other words, while readers should never transmit sensitive information to a site that does not use https://, the presence of this security feature tells you nothing about the trustworthiness of the site in question.

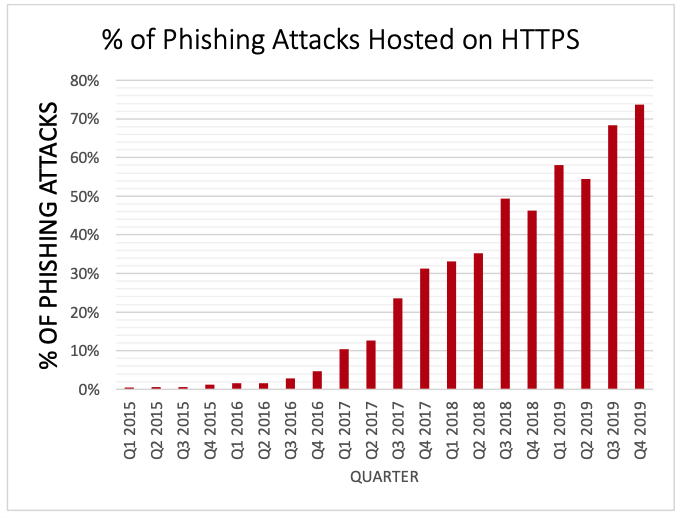

Here’s a sobering statistic: According to PhishLabs, by the end of 2019 roughly three-quarters (74 percent) of all phishing sites were using SSL certificates. PhishLabs found this percentage increased from 68% in Q3 and 54% in Q2 of 2019.

“Attackers are using free certificates on phishing sites that they create, and are abusing the encryption already installed on hacked web sites,” PhishLabs founder and CTO John LaCour said.

The truth is anyone can get an SSL certificate for free, and that’s a big reason why most phishing sites now have them. The other reason is that they help phishers better disguise their sites as legitimate, since many Web browsers now throw up security warnings on non-https:// sites.

KrebsOnSecurity couldn’t find any reliable information on how difficult it may be to obtain an SSL certificate for a .gov site once one has a .gov domain, but it is apparently not difficult for just about anyone to get their very own .gov domain name.

The U.S. General Services Administration (GSA), which oversees the issuance of .gov domains, recently made it a tiny bit more difficult to do so — by requiring all applications be notarized — but this seems a small hurdle for scam artists to clear.

Regardless, it seems the federal government is doing consumers a disservice with this messaging, by perpetuating the myth that the presence of “https://” in a link denotes any kind of legitimacy.

“‘Https’ does not mean that you are at the correct website or that the site is secure,” LaCour said. “It only indicates that the connection is encrypted. The server could still be misconfigured or have software vulnerabilities. It is good that they mention to look for ‘.gov’. There’s no guarantee that a .gov website is secure, but it should help ensure that visitors are on the right website.”

I should note that this misleading message seems to be present only on some federal government Web sites. For instance, while the sites for the GSA, the Department of Labor, Department of Transportation, and Department of Veterans Affairs all include the same wording, those for the Commerce Department and Justice Department are devoid of the misleading text, stating:

“This site is also protected by an SSL (Secure Sockets Layer) certificate that’s been signed by the U.S. government. The https:// means all transmitted data is encrypted — in other words, any information or browsing history that you provide is transmitted securely.”

Other federal sites — like dhs.gov, irs.gov and epa.gov — simply have the “An official website of the United States government” declaration at the top, without offering any tips about how to feel better about that statement.

I always say that HTTPS only ensures the devil that his communications with you are secure.

That’s awesome. May I use that line in my organization? 🙂

Sure, why not? He didn’t say the phrase was copy-righted.

Because, technically, it IS copyrighted unless the originator places it in the public domain. Please, always ask permission!

Posting it as a comment on this site, would be considered public domain.

And phrases do not automatically have a copyright even if you keep it out of public domain. That may be a case to “claim” a copyright. But intellectual property classification is not a given, and the person claiming the copyright bears the burden of proof.

Phrases are trademarked. bodies of work are copyrighted. He would have to trademark his phrase.

Copyright has triviality limitations. Please don’t try to practice IP law without going to law school.

I’ve had this exact same beef with Google Chrome. Any site you visit without HTTPS is deemed “Not Secure” in the address bar. “Not Encrypted” yes, but Not secure is not correct.

That’s not the same at all. Krebs is saying being encrypted does not guarantee security or authenticity. However being unencrypted ensures you have neither because it makes MITM attacks trivial; Chrome’s messaging is perfectly reasonable.

I’d agree with Chrome on that one, if the website communication isn’t HTTPS then the chances of it being “secure” are nil.

I had the same thoughts when I went to the census site, thanks Brian!

HTTPS only ensures against “man in the middle attacks “by highly encrypting the data between the clients browser and server host.

I would quibble with that. That does NOT ensure against man in the middle attacks. In fact in some businesses they purposefully use methods to do man in the middle in order to do filtering of traffic and websites.

I pleasantly disagree with you, if you use 256 AES encryption end to end, and use real good fire-walling practices you will cut down the chances of intrusion by a huge amount. It’s all in the setup and deploying !

I believe that what was meant here was that browsing from a corporate device, on a corporate network where the computer trusts the domain and where the company practices deep packet inspection (DPI) to analyse traffic on the network man-in-the-middle attacks are very possible if the man in the middle is the company or at least in control of the certification mechanisim used to do DPI which would allow them to decrypt and re-encrypt traffic to HTTPS secured sites.

TO some degree, DPI == MITM – although generally only used for good and with the consent (where required), if not with the knowledge, of the person browsing.

Deep Packet Inspection (DPI) is not the right terminology. DPI is what firewalls do to see some basic layer 7 information (as opposed to just layers 3 and 4) to help enforce policy with firewall rules.

Break and Inspect (B&I) or SSL Inspection, is the sanctioned MITM technology.

I disagree a bit. The .gov sites one can get for fraud in the link are not going to have domains like the official ones – treasury.gov, whitehouse.gov, census.gov, etc etc.

The bar is asking people to look for the .gov and the https://, but one would presume they would notice if the address in the middle is exeterri.gov, but the site is pretending to be the census, that would be sketchy.

@Anon:

On the contrary, way too many people pay way too little attention to what’s in the middle. It’s so easy to send people to, for example, CEN5US.GOV (viewed in Arial Calibri or even Times Roman) and they’ll never notice the subtle difference. Happens all the time.

The “advice” these sites have given — no matter how well intended — is a mess and should be removed.

The URL my2020census.gov is actually absolutely terrible. census.gov would be a proper, simple, hard to counterfeit url.

I’d hope when reviewing gov application, they also check that the name makes sense. Otherwise, it would be easy to register 2020census.gov, then use my.2020census.gov.

I was very disappointed to see the URL chosen for the census… and not have the authority to fire the nitwit who selected it. That childish “my” branding is right out of the 1990s. What was wrong with 2020.census.gov ? Using the Bureau’s primary domain like that (and squatting on 2020census.gov for good measure) would’ve made it more difficult to spoof.

I have been saying in this forum and many others for more than 10 years that the claims of security by observation were bogus but no one has listened. The only way to protect users is to have login credentials unique to the user that only the user knows to prevent hapless users being fooled.

And if you’re using the latest version of Chrome, it no longer shows the “https” part of the URL, only the lock.

Just me speaking personally, but I’m sure the US Web Design System would love to get a pull request — it’s an open source project. https://designsystem.digital.gov/

Someone made one https://github.com/uswds/uswds/pull/3373

When did we retcon the purpose of SSL/TLS to be limited only to confidentiality? Literally the first bullet point in the first section of RFC 8846 is “Authentication”: https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc8446. Specifically it says “The server side of the channel is always authenticated”. It seems pretty disingenuous to say SSL “merely signifies the data being transmitted back and forth between your browser and the site is encrypted”. Granted since the major browser vendors decided that having actual humans involved in the validation of organizations requesting certificates is of no value, we basically turned the “authentication” into “can control DNS responses sent to a CA”. But that doesn’t mean authentication was never part of the intent.

and this is relevant and matters today to regular people who don’t read RFCs how?

Samuel makes an excellent point. The first and primary purpose of the SSL protocol was authenticity. Which is why there has been a move to migrate http sites to https. The challenge is the cryptography isn’t easy. Asking the general public to read the certificate details to establish that the correct URL has been bound to the certificate and the that the chain of trust is valid and the certificate is still valid is a non-starter. Once again we are faced with the competing issues of usability vs security. The US Gov approach to break through this conundrum with additional text is equally a non-starter.

At the current state of our technology, education and user experience we need to accept that, like it or not, if we are going to help the end-user be more aware and less prone to compromise then we need to be much better at explaining the technology and what is happening. Secondly they need to be aware that they need to understand at least a bit more than they do now!

Not least because it would help them understand why certain commercial VPN product suppliers are selling them snake oil based on the marketing FUDD factor. This is one of those issues that Brian would be well placed to opine about. They are the sort of suppliers that are deliberately with malice aforethought breaking the https connection and eroding security totally!

Though Anon makes the point that someone cannot have a website like whitehouse.gov, there are very bad websites that include a restricted domain as part of a malicious website. The easy way is something that is trivial for security pros to id as fake:

https://www.cdc-gov.org or some other

There are other ways to impersonate legit website by adding a / after the real and legit domain, in effect embedding the legit domain in a malicious domain. This can make it really hard to figure out if the URL is legit or not because some are and some aren’t.

Does anyone have any way of figuring out the legitimacy of such URLs?

Oh sh*t, my padlock isn’t green on krebs-on-security! I must be in trouble 🙂

Chrome said goodbye to the green padlock on HTTPS a long time ago. You have to click it to see the rating.

I keep my horsey in a green padlock, er, um, paddock…

Our government is the worst when it comes to security practice – so they’d be the LAST place I look for tips. We read about breaches at .gov sites all the time; I’m not even sure our secret military data is safe any more!

I usually rely on the Web of Trust app to assess whether a site is legitimate or not – but government sites are not always rated thru that handy site adviser; so one has to look carefully on how the URL is spelled and also if there are more than one search results with similarities to choose from. Of course many people probably hover the mouse cursor over the link to see if it is the expected address. I usually always do a search rather than trust any links I get in email or on web pages. I’m sure most readers here already know this, and probably better than I.

Thanks Brian for putting that census address link here; I realized I hadn’t done my civic duty, to fill out my report, so I immediately went there to complete the job.

Have the few sites with bad wording been asked to revise it?

Umm, in the second paragraph before the graph titled “% of phishing sites…”, the quote of PhishingLabs is accurate but does not agree with the graph. The percentage of phishing site using https in Q4 2019 is over 70%, according to the graph — not 54%. Perhaps Phishing Labs should correct their statement so your (revised) quote from their web site will make sense?

Oops, please discard my last comment. After re-reading it one more time, I see that is is accurate, just not phrased the way I expected.

I apologize for wasting your time.

Travis

USG should set a better, consistent, example by using EV certificates on all, not just some websites. And browsers (e.g. Firefox) should once again make the type of certificate clearly visible in the address bar.

Richard — Re “…browsers (e.g. Firefox) should once again make the type of certificate clearly visible in the address bar”:

In Firefox, clicking the padlock icon in address bar takes you to Site Info/Security; then from there click the arrow –>, see “Verified by __”, and “More Information” at the bottom. Click More Information to get full security display (on Win 7 — probably works the same on Win 8, Win 10?)

Correct. But a few versions ago Firefox presented this information in the address bar itself – no clicking down through several menu layers to see whether it is an EV certificate or not. This allowed at-a-glance verification that a web site was owned by who it claimed to be. A return to that format, along with adding the feature to the iOS version and other browsers would be helpful.

Why the certificates organization provide certificates to phishers.? !!

Because the free certificate authorities fail to do their due diligence to insure that the certificates they issue are actually going to legitimate websites and will issue certificates under their root authority automatically for any submitted website.

If the phishers and scammers had to pay for their certificates we’d see a lot less of the criminals using HTTPS.

Hold Certificate Authorities legally, criminally and financially accountable for misuse of their certificates to impersonate legitimate websites.

They are supposed to be the “authority” and the public is supposed to “trust” these sites based on delegated trust of the CA.

Right now, we have to trust the browser to trust the CAs. So if LetsEncrypt has 60% of its certs as benign, and 40% malicious (example)… at what point do browsers revoke that trust?

Browsers revoked their trust in Symantec Root CAs a few years back because of bad security practices.

Perhaps we need more of that.

Browsers have a duty to their users, to consider the security practices of Certificate Authorities. But they don’t have a huge incentive since they their users don’t pay them for this service.

We may need legal consequences for CAs who issue certs without due diligence. At least for the most trusted types of certificates (as long as browsers validate them in more obvious ways).

Yet another shining example of “Idiots In Authority” if not outright intentional gas-lighting.

Y’all do realize that SSL break and inspect is a reality, don’t you?

Which means the communication stream is not inherently secure due to encryption…

Just sayin’…

It’s not exactly the reality for non enterprise users.

For the browser to not throw errors at B&I… it has to be explicitly and permanently trusted. This would require either a previous compromise of the system, or something like a Group Policy being enforced to domain joined systems.

These B&I certs are special, and not handed out by public CAs. They are allowed to be used with a blanket wildcard, on any/every HTTPS website. And thus, are certs that browsers will not trust with a default configuration.

If a browser is trusting a cert for B&I, then it was put there by an enterprise policy, or the attacker has already compromised the machine.

“This site is also protected by an SSL (Secure Sockets Layer) certificate that’s been signed by the U.S. government. The https:// means all transmitted data is encrypted — in other words, any information or browsing history that you provide is transmitted securely.”

First off, certificate hasn’t been signed by the “U.S. Government” , that is unless the U.S. government owns Digicert, Inc. which I don’t think they do. The website is encrypted by a certificate supplied by Digicert. And Digicet vouches that the website is who they claim they are. But it’s certainly not “signed by the U.S. government”. Very misleading phraseology there.

Second, it’s nice to know it’s encrypted but what the hell do they need to know my “browsing history” for. That seems quite odd to add to that statement. Just wondering why they included that. Seems odd.

https://www.commerce.gov/

Yeah, very weird.

Sounds like a statement that got passed from a technical person, through the hands of several non-technical people, who revised it to “simplify” it.

Recording site visits, probably got translated into the term “browsing history” because that is what the layperson may understand. The result, however, is confusing because the “browsER history” would imply the inclusion of other website traffic.

Also, right about Digicert. Many government websites do (or did) have their certs signed by the government CA…. But of all the sites listed… none of these have been. Commerce seems the only banner that makes that claim though.

Gotta arrest them to keep them from defecting to the West.

I understand that https is not always implemented correctly, which can make the https encryption useless. Is there a website or tool to check the implementation and report on any issues of https on a given site?

Yep… https://www.ssllabs.com/ssltest/

Thank you

It is not true that HTTPS “signifies the data being transmitted back and forth between your browser and the site is encrypted”

HTTPS only insures that data being downloaded is encrypted. It does not offer that insurance for uploaded data.

Here are two recent blogs on the subject

michael horowitz. com /submit.php

askleo.com/how-can-an-https-website-still-not-be-secure/

In fairness, this is a very common mis-conception. Falsehoods repeated over and over and over become true.

Looks like your comment is the falsehood.

Please actually read from the links you posted… because they do NOT support your comment’s explanation.

HTTPS is indeed encrypted both ways. The issue of unencrypted data has nothing to do with direction (download/upload).

Your confusion, and attempt to confuse others, has nothing to do specifically with uploading data. But rather, that there can be HTTP unencrypted elements within an HTTPS webpage.

Yes, an HTTPS site’s input field “could” send an unencrypted HTTP POST request… but that is also true for HTTP unencrypted iframes too.

The important takeaway is not about directionality, but rather that a single website contains lots of resources that all make their own web request. It isn’t enough to only look at the URL bar… but you must inspect the whole page.

There are many browser plugins that will warn if a website contains “mixed content”.

https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/Security/Mixed_content

WFHguy is Michael Horowitz, a blogger who likes to come on my site to pick nits in my stories, post links back to his site, and throw a temper tantrum on Twitter when his comments here are held for moderation (by the comments system, not by me).

I let just about anyone comment here, including many of the cybercriminals who have nothing nice to say about yours truly. But as I told Michael, the one thing I can’t stand is being accused of something I didn’t do. People who accuse me of censoring comments soon find their comments held for moderation permanently.

The claim is also made that a “.gov” domain name implies legitimacy. But my understanding it that it is quite easy to gen up some fake letterhead for a city or whatever and get a .gov name registered. 🙁

At the bottom of https://fiscal.treasury.gov/GoDirect/fraud/index.html

“Don’t be a victim of identity theft. Visit http://www.IdentityTheft.gov to learn more.”

I guess they’re right, http. Because https isn’t secure.

The 2020 Census is a disaster in the making. When those in charge make statements such as ‘hundreds of thousands of positions available,’ one has to wonder how much of a grip that team really has on mathematics. I have already written to them with my thoughts on this. I do hope we get a more accurate head count than ‘hundreds of thousands’.

As for security and privacy of data, it’s difficult to believe there can be privacy when the 2020 census organizers contract with Office Depot to process identity verifications for those ‘hundreds of thousands’ of employees, but neglects to tell the contractor that posting the password to the DoC system on a sticky note on the front of the screen, and leaving that system unmonitored on the sales floor, probably isn’t a good idea.

I contacted the DoC on this, too, but apparently they didn’t find the security of the personal data of those ‘hundreds of thousands’ of census workers a concern as the sticky note persists at this particular location.

I won’t even get into the simplicity of the password itself, but suffice to say I could access any one of these DoC systems, anywhere in the country, if i was inclined to do so.

Un-flippen-believable.

One small point… this isn’t about extended verification, is it?

Your site gets a black padlock: I think green was reserved for EV, but there are plenty of people out there (Troy Hunt is one: see https://www.troyhunt.com/extended-validation-certificates-are-dead/) who reckon EV is not worth the paper it isn’t written on. But then government IT tends to take time to catch up….