Analysis of open source information on the cybercriminal infrastructure likely used to siphon 80 million Social Security numbers and other sensitive data from health insurance giant Anthem suggests the attackers may have first gained a foothold in April 2014, nine months before the company says it discovered the intrusion.

The Wall Street Journal reported last week that security experts involved in the ongoing forensics investigation into the breach say the servers and attack tools used in the attack on Anthem bear the hallmark of a state-sponsored Chinese cyber espionage group known by a number of names, including “Deep Panda,” “Axiom,” Group 72,” and the “Shell_Crew,” to name but a few.

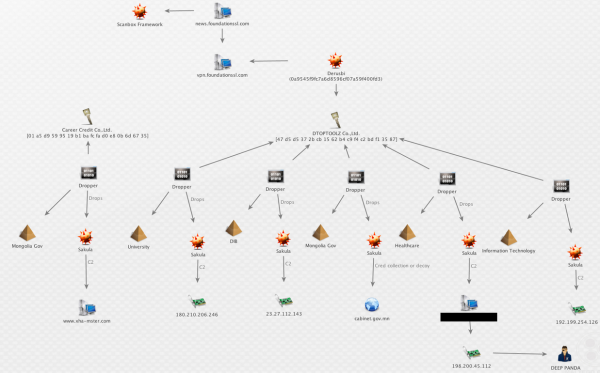

Deep Panda is the name given to this group by security firm CrowdStrike. In November 2014, Crowdstrike published a snapshot of a graphic showing the malware and malicious Internet servers used in what security experts at PriceWaterhouseCoopers dubbed the ScanBox Framework, a suite of tools that have been used to launch a number of cyber espionage attacks.

A Maltego transform published by CrowdStrike. The graphic is intended to illustrate some tools and Internet servers thought to be closely tied to a Chinese cyber espionage group that CrowdStrike calls “Deep Panda.”

Crowdstrike’s snapshot (produced with the visualization tool Maltego) lists many of the tools the company has come to associate with activity linked to Deep Panda, including a password stealing Trojan horse program called Derusbi, and an Internet address — 198[dot]200[dot]45[dot]112.

CrowdStrike’s image curiously redacts the resource tied to that Internet address (note the black box in the image above), but a variety of open source records indicate that this particular address was until very recently the home for a very interesting domain: we11point.com. The third and fourth characters in that domain name are the numeral one, but it appears that whoever registered the domain was attempting to make it look like “Wellpoint,” the former name of Anthem before the company changed its corporate name in late 2014.

We11point[dot]com was registered on April 21, 2014 to a bulk domain registration service in China. Eight minutes later, someone changed the site’s registration records to remove any trace of a connection to China.

Intrigued by the fake Wellpoint domains, Rich Barger, chief information officer for Arlington, Va. security firm ThreatConnect Inc., dug deeper into so-called “passive DNS” records — historic records of the mapping between numeric Internet addresses and domain names. That digging revealed a host of other subdomains tied to the suspicious we11point[dot]com site. In the process, Barger discovered that these subdomains — including myhr.we11point[dot]com, and hrsolutions.we11point[dot]com – mimicked components of Wellpoint’s actual network as it existed in April 2014.

“We were able to verify that the evil we11point infrastructure is constructed to masquerade as legitimate Wellpoint infrastructure,” Barger said.

Another fishy subdomain that Barger discovered was extcitrix.we11point[dot]com. The “citrix” portion of that domain likely refers to Citrix, a software tool that many large corporations commonly use to allow employees remote access to internal networks over a virtual private network (VPN).

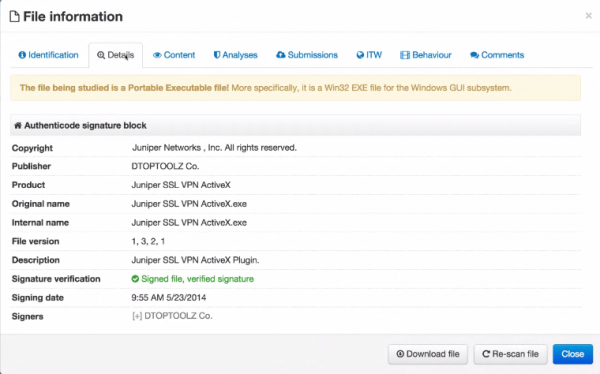

Interestingly, that extcitrix.we11point[dot]com domain, first put online on April 22, 2014, was referenced in a malware scan from a malicious file that someone uploaded to malware scanning service Virustotal.com. According to the writeup on that malware, it appears to be a backdoor program masquerading as Citrix VPN software. The malware is digitally signed with a certificate issued to an organization called DTOPTOOLZ Co. According to CrowdStrike and other security firms, that digital signature is the calling card of the Deep Panda Chinese espionage group.

CONNECTIONS TO OTHER VICTIMS?

As noted in a story in HealthITSecurity.com, Anthem has been sharing information about the attack with the Health Information Trust Alliance (HITRUST) and the National Health Information Sharing and Analysis Center (NH-ISAC), industry groups whose mission is to disseminate information about cyber threats to the healthcare industry.

A news alert published by HITRUST last week notes that Anthem has been sharing so-called “indicators of compromise” (IOCs) — Internet addresses, malware signatures and other information associated with the breach. “It was quickly determined that the IOCs were not found by other organizations across the industry and this attack was targeted a specific organization,” HITRUST wrote in its alert. “Upon further investigation and analysis it is believed to be a targeted advanced persistent threat (APT) actor. With that information, HITRUST determined it was not necessary to issue a broad industry alert.”

An alert released by the Health Information Trust Alliance (HITRUST) about the APT attack on Anthem.

But a variety of data points suggest that the same infrastructure used to attack Anthem may have been leveraged against a Reston, Va.-based information technology firm that primarily serves the Department of Defense.

A writeup on a piece of malware that Symantec calls “Mivast” was produced on Feb. 6, 2015. It describes a backdoor Trojan that Symantec says may call out to one of a half-dozen domains, including the aforementioned extcitrix.we11point[dot]com domain and another — sharepoint-vaeit.com. Other domains on the same server include ssl-vaeit.com, and wiki-vaeit.com. Once again, it appears that we have a malware sample calling home to a domain designed to mimic the internal network of an organization — most likely VAE Inc. (whose legitimate domain is vaeit.com).

Barger and his team at ThreatConnect discovered that the sharepoint-vaeit.com domain also was tied to a malware sample made to look like it was VPN software made by networking giant Juniper. That malware was created in May 2014, and was also signed with the DTOPTOOLZ Co. digital certificate that CrowdStrike has tied to Deep Panda.

In response to an inquiry from KrebsOnSecurity, VAE said it detected a targeted phishing attack in May 2014 that used malware which phoned home to those domains, but the company said it was not aware of any successful compromise of its users.

In any case, the Symantec writeup on Mivast also says the malware tries to contact the Internet address 192[dot]199[dot]254[dot]126, which resolved to just one Web domain: topsec2014[dot]com. That domain was registered on May 6, 2014 to a bulk domain reseller who immediately changed the registration records and assigned the domain to the email address topsec_2014@163.com. That address appears to be the personal email of one Song Yubo, a professor with the Information Security Research Center at the Southeast University in Nanjing, Jiangsu, China.

Yubo and his university were named in a March 2012 report, “Occupying the Information High Ground: Chinese Capabilities for Computer Network Operations and Cyber Espionage,” (PDF) produced by U.S. defense contractor Northrop Grumman Corp. for the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission. According to the report, Yubo’s center is one of a handful of civilian universities in China that receive funding from the Chinese government to conduct sensitive research and development with information security and information warfare applications.

ANALYSIS

Of course, it could well be that this is all a strange coincidence, and/or that the basic information on Deep Panda is flawed. But that seems unlikely given the number of connections and patterns emerging in just this small data set.

It’s remarkable that the security industry so seldom learns from past mistakes. For example, one of the more confounding and long-running problems in the field of malware detection and prevention is the proliferation of varying names for the same threat. We’re seeing this once again with the nicknames assigned to various cyberespionage groups (see the second paragraph of this story for examples).

It’s also incredible that so many companies could see the outlines of a threat against such a huge target, and that it took until just this past week for the target to become aware of it. For its part, ThreatConnect tweeted about its findings back in November 2014, and shared the information out to its user base.

CrowdStrike declined to confirm whether the resource blanked out in the above pictured graphic from November 2014 was in fact we11point[dot]com.

“What I can tell you is that this domain is a Deep Panda domain, and that we always try to alert victims whenever we discover them,” said Dmitri Alperovitch, co-founder of CrowdStrike.

Also, it’s myopic for an industry information sharing and analysis center (ISAC) to decide not to share indicators of compromise with other industry ISACs, let alone its own members. This should not be a siloed effort. Somehow, we need to figure out a better — more timely way — to share threat intelligence and information across industries.

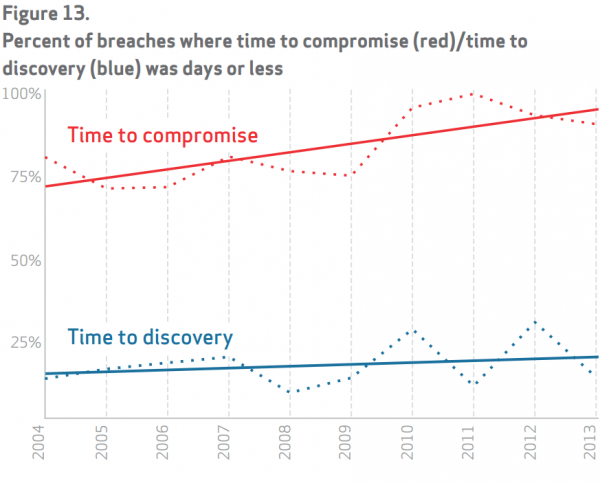

Perhaps the answer is crowdsourcing threat intelligence, or maybe it’s something we haven’t thought of yet. But one thing is clear: there is a yawning gap between the time it takes for an adversary to compromise a target and the length of time that typically passes before the victim figures out they’ve been had.

The most staggering and telling statistic included in Verizon’s 2014 Data Breach Investigations Report (well worth a read) is the graphic showing the difference between the “time to compromise” and the “time to discovery.” TL;DR: That gap is not improving, but instead is widening.

Then again, maybe this breach at Anthem isn’t as bad as it seems. After all, if the above data and pundits are to be believed, the attackers were likely looking for a needle in a haystack — searching for data on a few individuals that might give Chinese spies a way to better siphon military technology or infiltrate some U.S. defense program.

Perhaps, as Barger wryly observed, the Anthem breach was little more than the product of a class assignment — albeit an expensive and aggravating one for Anthem and its 80 million affected members. In May 2014, the aforementioned Southeast University Professor Song Yubo posted a “Talent Cup” tournament challenge to his information security students.

“Just as the OSS [Office of Strategic Services] and CIA used professors to recruit spies, it could be that this was all just a class project,” Barger mused.

If they had been a member, they might well have been more aware and aware earlier. So we have that going for us.

Kelly Jackson Higgins:

“Anthem isn’t a member of the healthcare industry’s information sharing and analysis center, the NH-ISAC, so the NH-ISAC got word of the attack via other members of the threat information-sharing community the morning after Anthem reported its massive data breach.

…Anthem’s attack, while targeted, in many ways was very similar to others out there in its methods and approach.”

http://www.darkreading.com/analytics/threat-intelligence/how-anthem-shared-key-markers-of-its-cyberattack/d/d-id/1319083?

Did Rich Barger/ThreatConnect ever contact Wellpoint/Anthem with the knowledge that potential Chinese hackers were attempting to masquerade as Wellpoint?