New research published this week could provide plenty of fresh fodder for Mirai, a malware strain that enslaves poorly-secured Internet of Things (IoT) devices for use in powerful online attacks. Researchers in Austria have unearthed a pair of backdoor accounts in more than 80 different IP camera models made by Sony Corp. Separately, Israeli security experts have discovered trivially exploitable weaknesses in nearly a half-million white-labeled IP camera models that are not currently sought out by Mirai.

A Sony IPELA camera. Image: Sony.

In a blog post published today, Austrian security firm SEC Consult said it found two apparent backdoor accounts in Sony IPELA Engine IP Cameras — devices mainly used by enterprises and authorities. According to SEC Consult, the two previously undocumented user accounts — named “primana” and “debug” — could be used by remote attackers to commandeer the Web server built into these devices, and then to enable “telnet” on them.

Telnet — a protocol that allows remote logons over the Internet — is the very same communications method abused by Mirai, which constantly scours the Web for IoT devices with telnet enabled and protected by factory-default passwords.

“We believe that this backdoor was introduced by Sony developers on purpose (maybe as a way to debug the device during development or factory functional testing) and not an ‘unauthorized third party’ like in other cases (e.g. the Juniper ScreenOS Backdoor, CVE-2015-7755),” SEC Consult wrote.

It’s unclear precisely how many Sony IP cameras may be vulnerable, but a scan of the Web using Censys.io indicates there are at least 4,250 that are currently reachable over the Internet.

“Those Sony IPELA ENGINE IP camera devices are definitely reachable on the Internet and a potential target for Mirai-like botnets, but of course it depends on the network/firewall configuration,” said Johannes Greil, head of SEC Consult Vulnerability Lab. “From our point of view, this is only the tip of the iceberg because it’s only one search string from the device we have.”

Greil said there are other undocumented functionalities in the Sony IP cameras that could be maliciously used by malware or miscreants, such as commands that can be invoked to distort images and/or video recorded by the cameras, or a camera heating feature that could be abused to overheat the devices.

Sony did not respond to multiple requests for comment. But the researchers said Sony has quietly made available to its users an update that disables the backdoor accounts on the affected devices. However, users still need to manually update the firmware using a program called SNC Toolbox.

Greil said it seems likely that the backdoor accounts have been present in Sony cameras for at least four years, as there are signs that someone may have discovered the hidden accounts back in 2012 and attempted to crack the passwords then. SEC Consult’s writeup on their findings is available here.

In other news, researchers at security firm Cybereason say they’ve found at least two previously unknown security flaws in dozens of IP camera families that are white-labeled under a number of different brands (and some without brands at all) that are available for purchase via places like eBay and Amazon. The devices are all administered with the password “888888,” and may be remotely accessible over the Internet if they are not protected behind a firewall. KrebsOnSecurity has confirmed that while the Mirai botnet currently includes this password in the combinations it tries, the username for this password is not part of Mirai’s current configuration.

But Cybereason’s team found that they could easily exploit these devices even if they were set up behind a firewall. That’s because all of these cameras ship with a factory-default peer-to-peer (P2P) communications capability that enables remote “cloud” access to the devices via the manufacturer’s Web site — provided a customer visits the site and provides the unique camera ID stamped on the bottom of the devices.

Although it may seem that attackers would need physical access to the vulnerable devices in order to derive those unique camera IDs, Cybereason’s principal security researcher Amit Serper said the company figured out a simple way to enumerate all possible camera IDs using the manufacturer’s Web site.

“We reverse engineered these cameras so that we can use the manufacturer’s own infrastructure to access them and do whatever we want,” Serper said. “We can use the company’s own cloud network and from there jump onto the customer’s network.”

Lior Div, co-founder and CEO at Cybereason, said a review of the code built into these devices shows the manufacturer does not appear to have made security a priority, and that people using these devices should simply toss them in the trash.

“There is no firmware update mechanism built into these cameras, so there’s no way to patch them,” Div said. “The version of Linux running on these devices was in some cases 14 years old, and the other code libraries on the devices are just as ancient. These devices are so hopelessly broken from a security perspective that it’s hard to really understand what’s going on in the minds of people putting them together.”

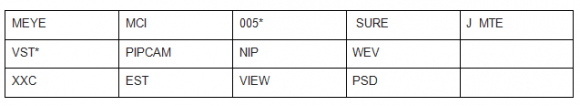

Cybereason said it is not disclosing full technical details of the flaws because it would enable any attacker to compromise them for use in online attacks. But it has published a few tips that should help customers determine whether they have a vulnerable device. For example, the camera’s password (888888) is printed on a sticker on the bottom of the devices, and the UID — also printed on the sticker — starts with one of these text strings:

The sticker on the bottom of the camera will tell you if the device is affected by the vulnerability. Image: Cybereason.

“People tend to look down on IoT research and call it junk hacking,” Cybereason’s Yoav Orot wrote in a blog post about its findings. “But that isn’t the right approach if researchers hope to prevent future Mirai botnet attacks. A smart (insert device here) is still a computer, regardless of its size. It has a processor, software and hardware and is vulnerable to malware just like a laptop or desktop. Whether the device records The Walking Dead or lets you watch your cat while you’re at work, attackers can still own it. Researchers should work on junk hacking because these efforts can improve device security (and consumer security in the process), keep consumer products out of the garbage heap and prevent them from being used to carry out DDoS attacks.”

The discoveries by SEC Consult and Cybereason come as policymakers in Washington, D.C. are grappling with what to do about the existing and dawning surge in poorly-secured IoT devices. A blue-ribbon panel commissioned by President Obama issued a 90-page report last week full of cybersecurity policy recommendations for the 45th President of the United States, and IoT concerns and addressing distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks emerged as top action items in that report.

Meanwhile, Morning Consult reports that U.S. Federal Communications Commission Chairman Tom Wheeler has laid out an unexpected roadmap through which the agency could regulate the security of IoT devices. The proposed certification process was laid out in a response to a letter sent by Sen. Mark Warner (D-Va.) shortly after the IoT-based attacks in October that targeted Internet infrastructure company Dyn and knocked offline a number of the Web’s top destinations for the better part of a day.

Morning Consult’s Brendan Bordelon notes that while Wheeler is set to step down as chairman on Jan. 20, “the new framework could be used to support legislation enhancing the FCC’s ability to regulate IoT devices.”

It’s amazing that there are still vulnerable devices out there

It’s also amazing that you can get the first comment very quickly.

And, it is so easy to defer responsibility. It happens in many industries in order to save face.

Is there a list of IoT things that have been tested by such security researchers and found to be (relatively) secure? It seems like insecurity is the norm in the IoT space, so if I simply avoid buying ones that are known to be broken, what I bought will probably be broken shortly after purchasing it. Can we name and fame the ones who do it right?

Seems like this would be a good time for Consumers Reports to step up to the plate in the 21st century …

Once again “security researchers” have proven they they are a good research department for the malware writers. Why don’t they just contact the manufacturers of these exploitable devices, tell them about their poor security, and leave it at that?

Regards,

We tried contacting the vendors several times. They never responded and that usually what happens in those cases. We chose not to publicly disclose our exploit code because we did not wanted to help any bad guys.

Not to get off topic, but how do you avoid claims or suspicion of hacking, or gaining unauthorized access to these devices? Are you getting authorization first? Just curious since this is my field. Makes it tough for researchers who seek to help.

We got about 30 cameras… We never accessed a camera we did not own

Why? Because in most instances the response they would get is “Buzz off!” or “Our attorneys will be in contact shortly”, if even that polite.

Because these manufacturers often ignore researchers reaching out to them – assuming the researchers can even find someone to contact. Like that white label product, it’s probably all made by the same Chinese manufacturer that doesn’t have a public point of contact at all. Not all manufacturers even have a security or support contact. They literally don’t care. Sometimes, even if they do have an active contact the manufacturer may still never issue a fix even if the information is under active exploit.

Just because the researchers haven’t disclosed their research doesn’t mean that information isn’t already available to malicious software already. The people that commission and/or write software for malicious use have deep pockets and resources along with considerable motivation to find exploitable software. It is always in the customer’s best interest to have this information along with any possible workaround or patches offered by the manufacturer (if any) so that steps can be taken to mitigate any potential or actual damage.

A lot of these companies are cheap chinese stuff with no one to even directly contact. White box electronics, or rebranded stuff so the company selling it may not even have much control over it.

Responsible disclosure is largely a utopian ideal. Many, many security researchers’ findings are blown off as insignificant by large companies who are driven by the mantra: “well it’s cheaper to accept the risk than to mitigate it.” Many won’t take action until there is media pressure on them to fix it. The researchers in question didn’t release any information that malicious individuals don’t already have and they didn’t actively provide them with specific details or working PoC exploits. Bad guys don’t typically publicly broadcast what they know…

As if the bad guys don’t know? doh.

Because those manufacturers don’t care that their products are unsafe. They have sold it and made their 42 cents and are long gone. Also, the malware (and the bad actors, already exist. Do you really think there will be no if researchers stop reporting about it? Really? Really?? If we stop talking about it then it will go away. OK. Let’s all stick our collective heads in the sand and pray to Santa.

People on this site and elsewhere wonder why I have such an issue with Sony…….well, this is part of why.

Meanwhile over in the UK more of the same.

http://www.theregister.co.uk/2016/12/06/wifi_looting_router_hacking/

Hi Brian,

Great article, as always. A quick typo find for you: paragraph 8, sentence 2 contains a redundant “said”:

“But the researchers ***said said*** Sony has quietly made available to its users an update that disables the backdoor accounts on the affected devices.”

You have to love the discovery about the cameras being managed by a centralized cloud location that could own all of them. How long until that site gets owned and the entire brand is part of a botnet.

Ugh, nice work Brian! Great article again.

Ahg enought about this rotchilds enought is enough

Rotchilds leave them alone

Internet Service Providers can detect these cameras as easily as the hackers. A simple scan of their network (customers devices) If a Customer has a known defective device, the ISP can then simply put a proactive block on any such outbound attack on that Customer’s account and notify the customer of their findings and solutions.

how long until malware assigns those ‘defective device’ threat signatures to all the devices on a network, completely shutting it down by turning the threat prevention system against the network’s legitimate users?

Sounds good but a couple of sticky issues are raised:

> Can a customer hold the ISP responsible for damages for NOT identifying the customer’s camera was hacked?

> From a PR point of view, will customers like an ISP that examines each and every packet sent to and from the customer?

1. No.

2. They already do…

Cameras are made in China, total junk.

Still putting the back doors. North Korea hacked Sony and now they hack their cameras and check out the U.S.

“Shall we play a game?”

All this reminds me of when wireless networking first became available with insecure access and lousy encryption.

Nothing has changed from these manufacturers. Security by design, security by default means nothing.

“Nothing has changed from these manufacturers. Security by design, security by default means nothing.”

Perhaps this line should say, “Nothing has changed from these manufacturers. Insecure by design, insecure by default.”

Brian

Is there any possibility that these devices are manning the critical infrastructure facilities & the cyber criminals attack those facilities by compromising these devices ?

Sounds scary if yes.

My recommendation to solve this problem. Whitehat hackers disguise as blackhats, launch massive DDOS attacks at times when they have the most visibility:

1) during emergencies, targeting emergency response organizations

2) during important national events, e.g. elections, targeting news agencies

3) targeting major government websites, e.g. DMV, IRS around 4/15, healthcare.gov around signup deadline, etc.

This should do it.

Many of the Sony cameras are used by “authorities”? How ironic if their own cameras become part of an IoT botnet.

I worked with a Chinese manufacturer on an early IoT device. There were always backdoors, both hardware and software, to get into debug modes. For example, in one case, a certain combination of button presses and a paperclip pressed on the tiny reset switch on the back did the trick. Those backdoors were not removed for the production devices.

These devices will never be built with good security under the existing business climate. First, the product cycles are so short that just getting the basic functions to work correctly is considered a big success. For many consumer electronic devices, Christmas is a huge selling season and that drives the schedule. Software development happens in the spring from about February to April. The final “burn-in” date is in May. Then it hits production. Then shipping. It must be on the retailer’s shelf in August. Then marketing kicks in. And product design starts for the next year’s product, based on consumer feedback.

These devices are sold with the same business model of a book. There is no post-sale communication with the consumer. I’m certain that anyone finding a post-purchase product security flaw would not be heard. The business model does not include listening to that.

I should clarify about product feedback. To a manufacturer, the “consumers” are retailers, distributors, technology reviewers, and other industry partners. The actual purchaser of the device is not really a customer of the manufacturer.

If you keep that in mind, you will understand why a security researcher’s message to a manufacturer doesn’t get a response.

Does Mirai modify the Mac addresses of the devices? Just wondering if could black-list a mac address range at the router level(inconveniently at the same network as the device)? (firmware update)… or someway to limit incoming connections to such mac addresses from outside the network.

MAC addresses do not come from outside a network.

Oh wait you said connect to from the outside. Hmmm, still probably not workable. Too many tables to update.

So, if I configure my camera with a direct connection to my laptop, and then I’m behind a router with no open or forwarded ports to allow remote administration, is my camera safe?

Assume also that ipv6 is disabled on my router and on my internal network.

If we can get root access to our own devices, can we then remove the debug and other user accounts?

I see very little on the internet on securing these devices. Everything says “you are doomed”. 🙁

Has anyone created a “read-only” fork of the Mirai code to help end-users scan our own devices?

I don’t understand how the manufacturer web site can access the device if the device is behind a firewall that stops inbound connection attempts. Do the devices ping the manufacturer site periodically?

It sounds like they establish a persistent connection or something…

The idea is to enable the camera’s owner to access the camera via the vendor’s website. And the way to do that is for the camera to connect to the website (hopefully https:) and wait for a request to stream. The owner then connects to the same website and “logs into” “their” camera.

If the vendor doesn’t offer this service, each poor user has to figure out how to punch a hole in their firewall. Not to mention the difficulty in getting the public address of the camera. Which users consider to be a “pain”, and they would tend to blame the vendor for not allowing easy access to the camera.

As unfortunate as it is…..this is exactly what the situation is. In a word it’s “dependency”.

in the google searchbox type: router upnp

You mean Sony didn’t start taking security seriously and get their employees security training? Did they also not start hiring more expensive and more experienced engineers with security experience?

I figured with the absolutely nothing that was done to punish them in the past, that would surely work!

There is always some failure in security. With help of experts we minimize risks.