U.S. state and federal investigators are being inundated with reports from people who’ve lost hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars in connection with a complex investment scam known as “pig butchering,” wherein people are lured by flirtatious strangers online into investing in cryptocurrency trading platforms that eventually seize any funds when victims try to cash out.

The term “pig butchering” refers to a time-tested, heavily scripted, and human-intensive process of using fake profiles on dating apps and social media to lure people into investing in elaborate scams. In a more visceral sense, pig butchering means fattening up a prey before the slaughter.

“The fraud is named for the way scammers feed their victims with promises of romance and riches before cutting them off and taking all their money,” the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) warned in April 2022. “It’s run by a fraud ring of cryptocurrency scammers who mine dating apps and other social media for victims and the scam is becoming alarmingly popular.”

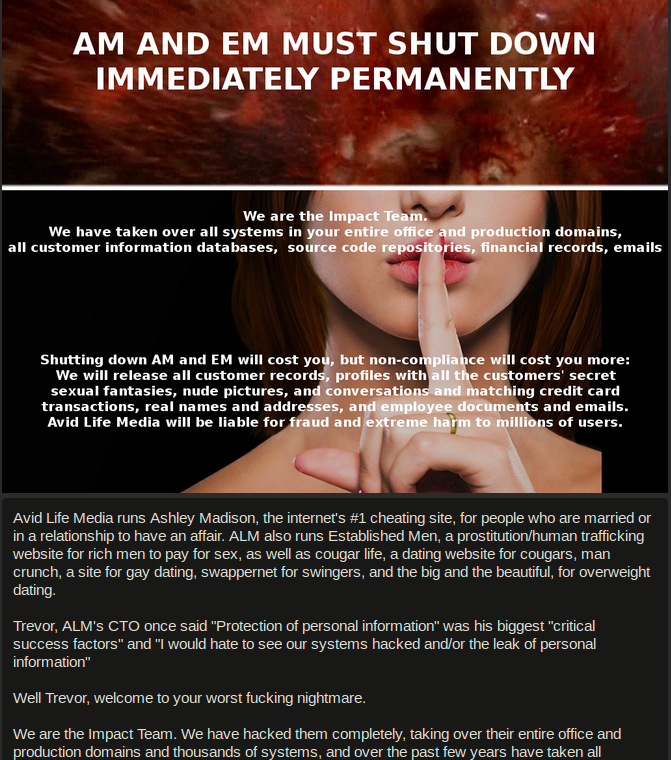

As documented in a series of investigative reports published over the past year across Asia, the people creating these phony profiles are largely men and women from China and neighboring countries who have been kidnapped and trafficked to places like Cambodia, where they are forced to scam complete strangers over the Internet — day after day.

The most prevalent pig butchering scam today involves sophisticated cryptocurrency investment platforms, where investors invariably see fantastic returns on their deposits — until they try to withdraw the funds. At that point, investors are told they owe huge tax bills. But even those who pay the phony levies never see their money again.

The come-ons for these scams are prevalent on dating sites and apps, but they also frequently start with what appears to be a wayward SMS — such as an instant message about an Uber ride that never showed. Or a reminder from a complete stranger about a planned meetup for coffee. In many ways, the content of the message is irrelevant; the initial goal to simply to get the recipient curious enough to respond in some way.

Those who respond are asked to continue the conversation via WhatsApp, where an attractive, friendly profile of the opposite gender will work through a pre-set script that is tailored to their prey’s apparent socioeconomic situation. For example, a divorced, professional female who responds to these scams will be handled with one profile type and script, while other scripts are available to groom a widower, a young professional, or a single mom.

‘LIKE NOTHING I’VE SEEN BEFORE’

That’s according to Erin West, deputy district attorney for Santa Clara County in Northern California. West said her office has been fielding a large number of pig butchering inquiries from her state, but also from law enforcement entities around the country that are ill-equipped to investigate such fraud.

“The people forced to perpetrate these scams have a guide and a script, where if your victim is divorced say this, or a single mom say this,” West said. “The scale of this is so massive. It’s a major problem with no easy answers, but also with victim volumes I’ve never seen before. With victims who are really losing their minds and in some cases are suicidal.”

West is a key member of REACT, a task force set up to tackle especially complex forms of cyber theft involving virtual currencies. West said the initial complaints from pig butchering victims came early this year.

“I first thought they were one-off cases, and then I realized we were getting these daily,” West said. “A lot of them are being reported to local agencies that don’t know what to do with them, so the cases languish.”

West said pig butchering victims are often quite sophisticated and educated people.

“One woman was a university professor who lost her husband to COVID, got lonely and was chatting online, and eventually ended up giving away her retirement,” West recalled of a recent case. “There are just horrifying stories that run the gamut in terms of victims, from young women early in their careers, to senior citizens and even to people working in the financial services industry.”

In some cases reported to REACT, the victims said they spent days or weeks corresponding with the phony WhatsApp persona before the conversation shifted to investing.

“They’ll say ‘Hey, this is the food I’m eating tonight’ and the picture they share will show a pretty setting with a glass of wine, where they’re showcasing an enviable lifestyle but not really mentioning anything about how they achieved that,” West said. “And then later, maybe a few hours or days into the conversation, they’ll say, ‘You know I made some money recently investing in crypto,’ kind of sliding into the topic as if this wasn’t what they were doing the whole time.”

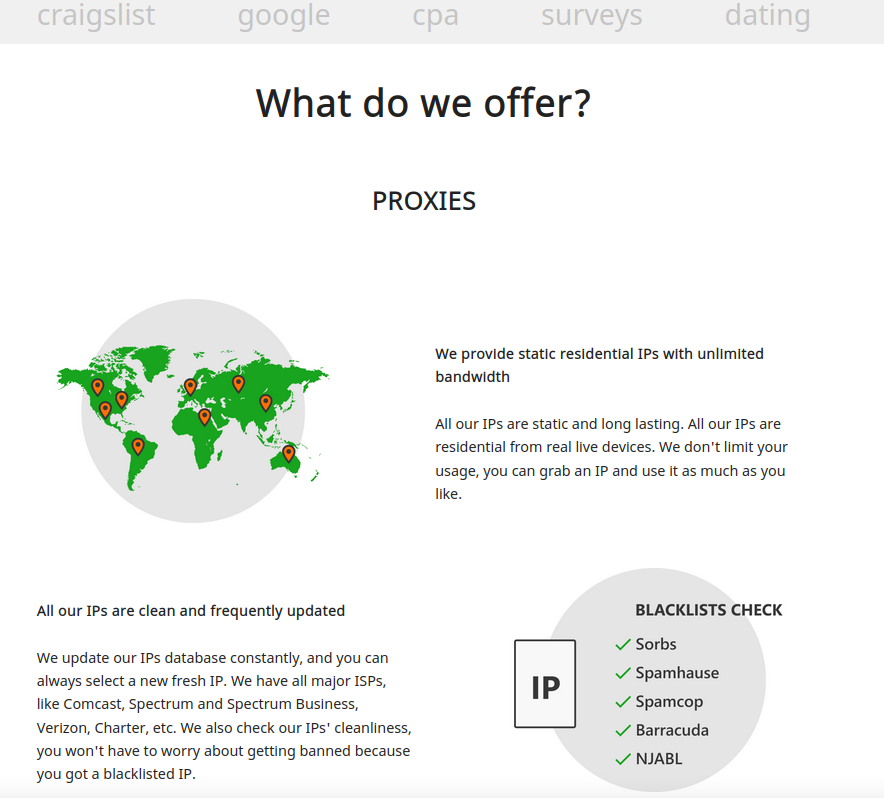

Curious investors are directed toward elaborate and official-looking online crypto platforms that appear to have thousands of active investors. Many of these platforms include extensive study materials and tutorials on cryptocurrency investing. New users are strongly encouraged to team up with more seasoned investors on the platform, and to make only small investments that they can afford to lose.

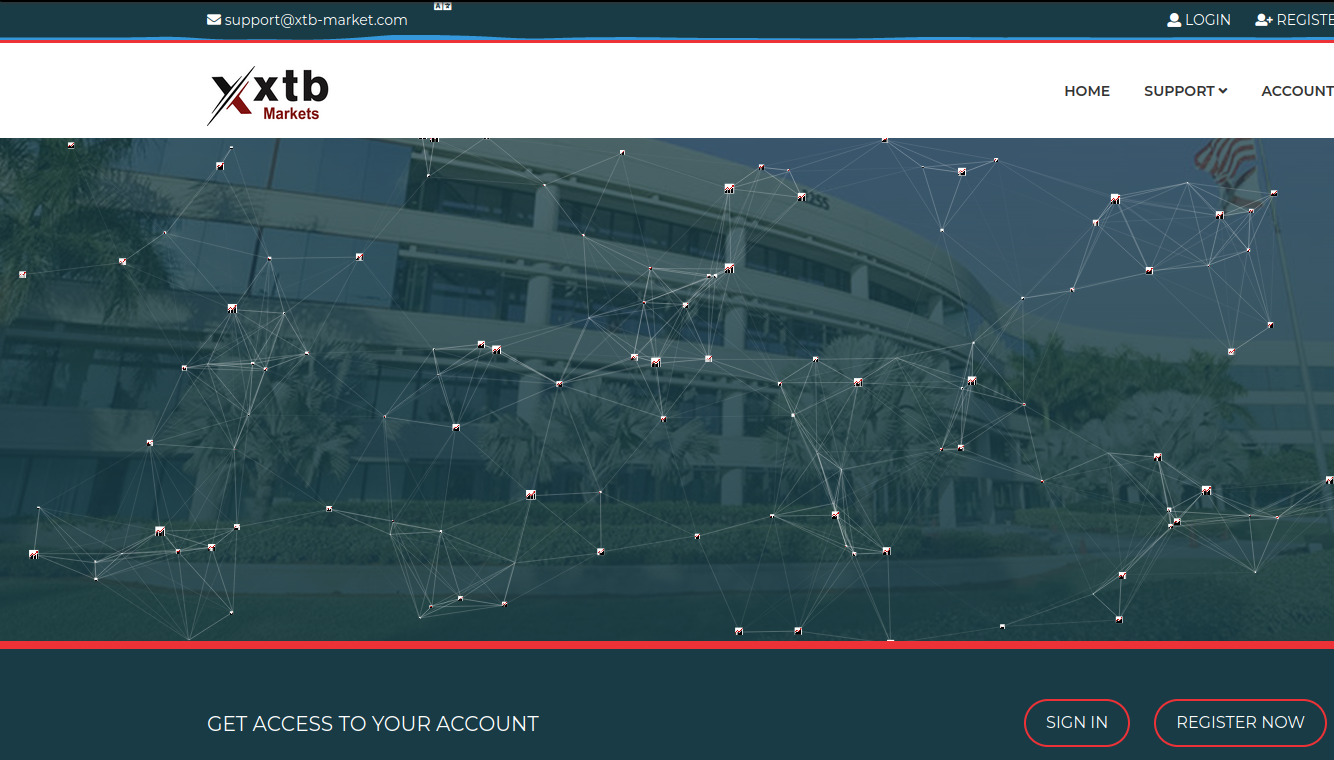

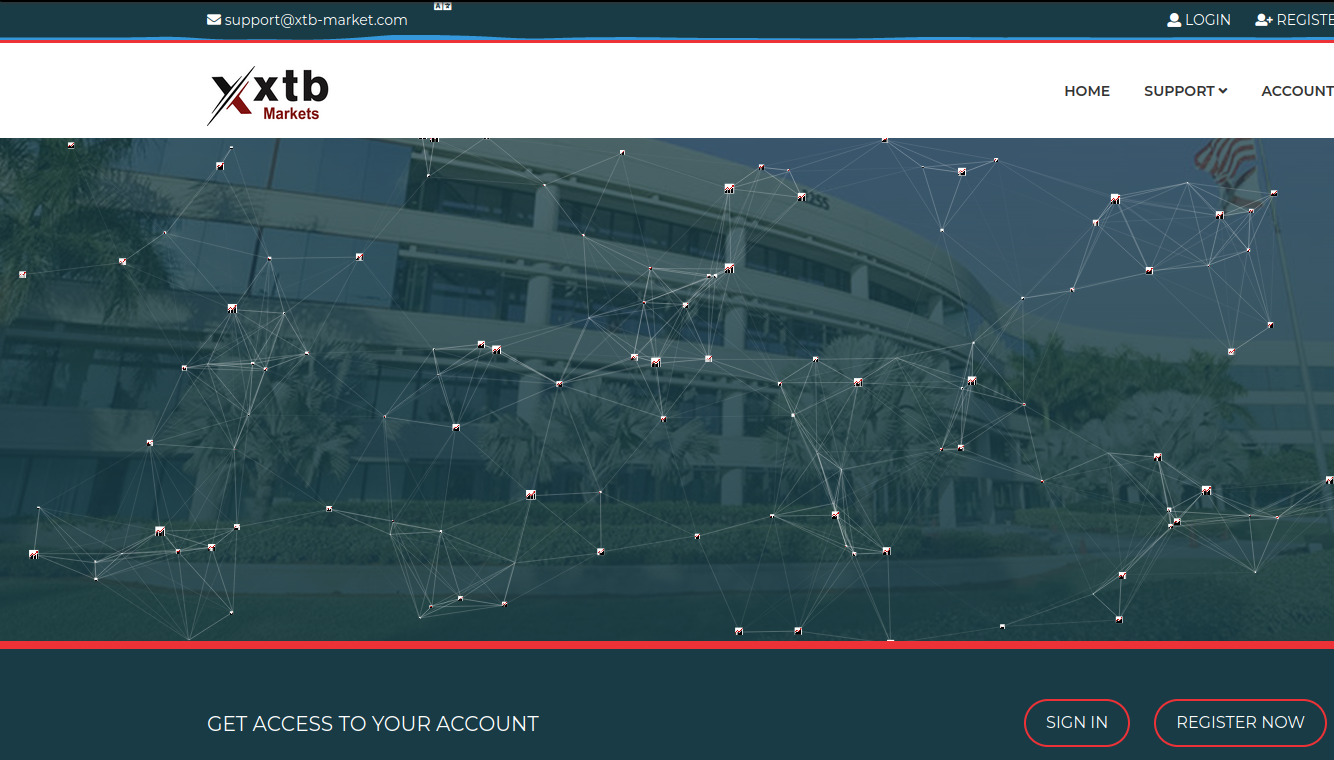

The now-defunct homepage of xtb-market[.]com, a scam cryptocurrency platform tied to a pig butchering scheme.

“They’re able to see some value increase, and maybe even be allowed to take out that value increase so that they feel comfortable about the situation,” West said. Some investors then need little encouragement to deposit additional funds, which usually generate increasingly higher “returns.”

West said many crypto trading platforms associated with pig butchering scams appear to have been designed much like a video game, where investor hype is built around upcoming “trading opportunities” that hint at even more fantastic earnings.

“There are bonus levels and VIP levels, and they’ll build hype and a sense of frenzy into the trading,” West said. “There are definitely some psychological mechanisms at work to encourage people to invest more.”

“What’s so devastating about many of the victims is they lose that sense of who they are,” she continued. “They thought they were a savvy, sophisticated person, someone who’s sort of immune to scams. I think the large scale of the trickery and psychological manipulation being used here can’t be understated. It’s like nothing I’ve seen before.”

A $5,000,000 LOSS

Courtney is a divorced mother of three daughters, says she lost more than $5 million to a pig butchering scam. She lives in St. Louis and has a background in investment finance, but only started investing in cryptocurrencies in the past year.

Courtney’s case may be especially bad because she was already interested in crypto investing when the scammer reached out. At the time, Bitcoin was trading at or near all-time highs of nearly $68,000 per coin.

Courtney said her nightmare began in late 2021 with a Twitter direct message from someone who was following many of the same cryptocurrency influencers she followed. Her fellow crypto enthusiast then suggested they continue their discussion on WhatsApp. After much back and forth about his trading strategies, her new friend agreed to mentor her on how to make reliable profits using the crypto trading platform xtb.com.

“I had dabbled in leveraged trading before, but his mentor program gave me over 100 pages of study materials and agreed to walk me through their investment strategies over the course of a year,” Courtney told KrebsOnSecurity.

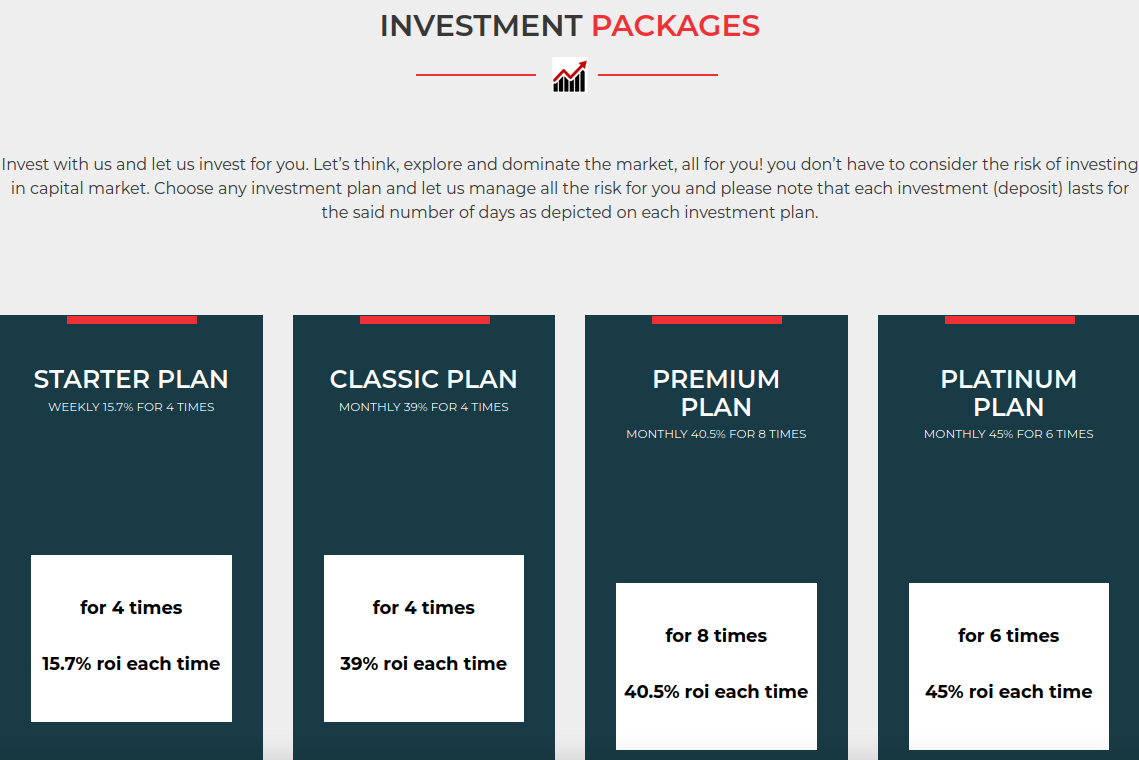

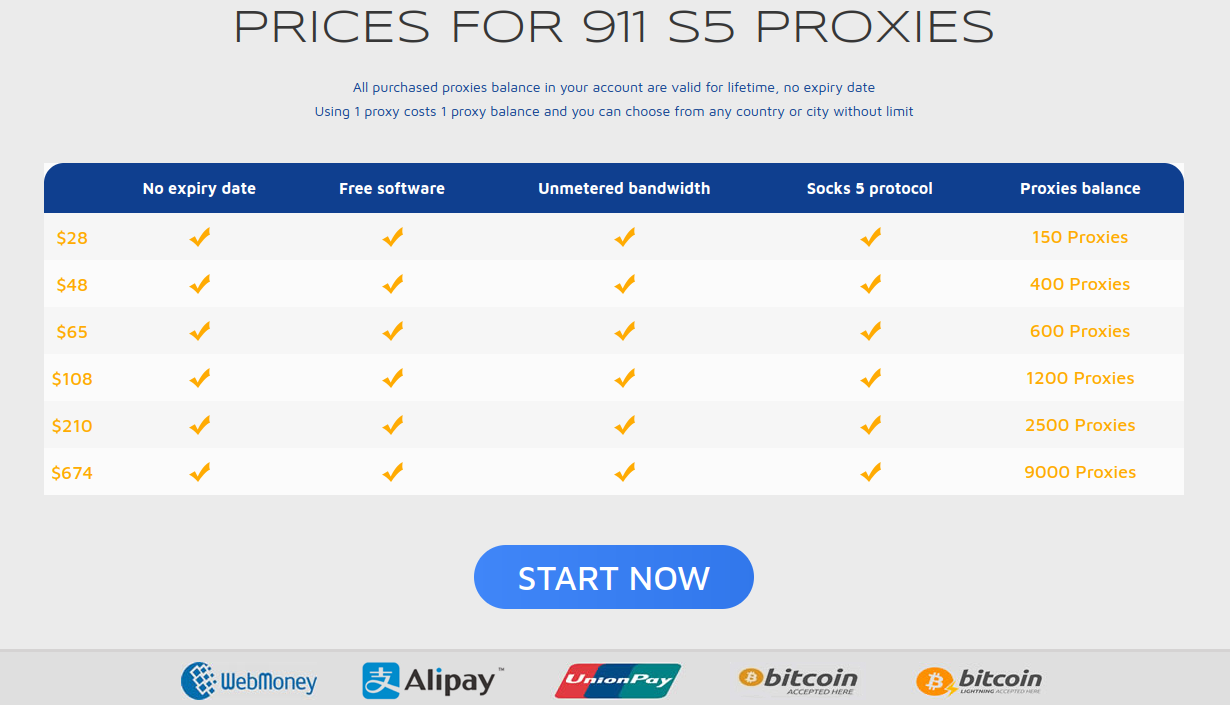

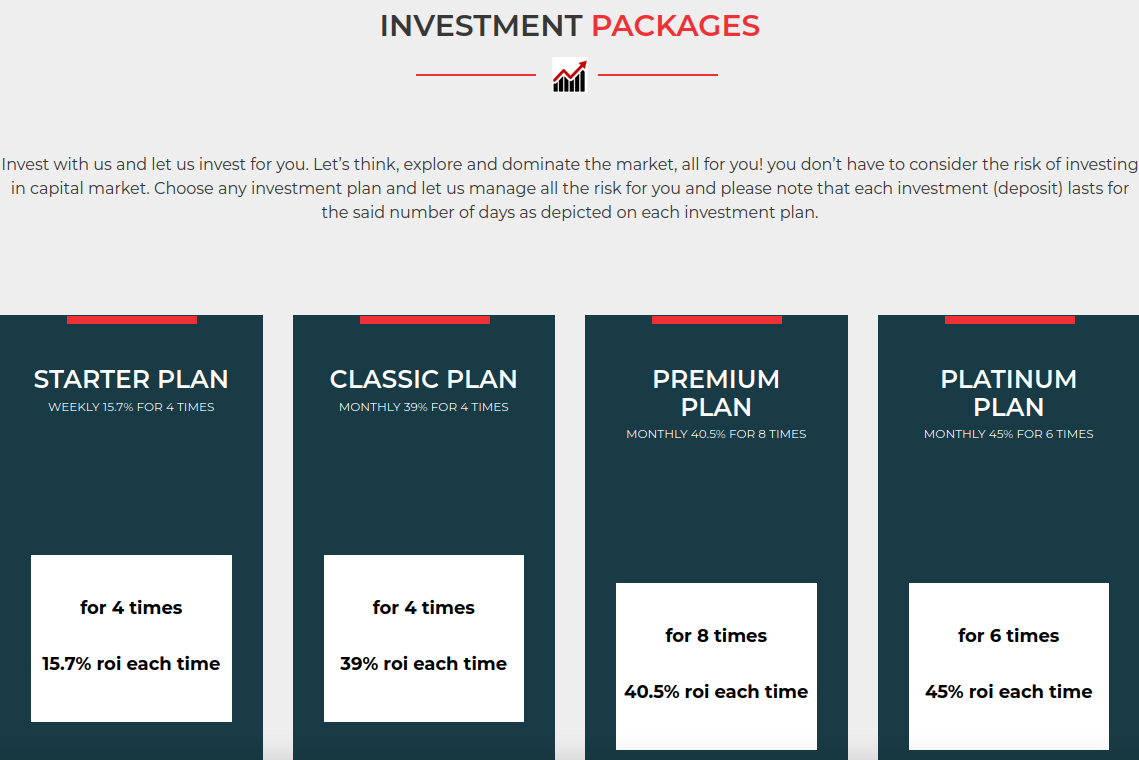

Courtney’s mentor had her create an account website xtb-market[.]com, which was made to be confusingly similar to XTB’s official platform. The site promoted several different investment packages, including a “starter plan” that involves a $5,250 up-front investment and promises more than 15 percent return across four separate trading bursts.

Platinum plans on xtb-market promised a whopping 45 percent ROI, with a minimum investment of $265,000. The site also offered a generous seven percent commission for referrals, which encouraged new investors to recruit others.

The now-defunct xtb-market[.]com.

While chatting via WhatsApp, Courtney and her mentor would trade side by side in xtb-market, initially with small investments ranging from $500 to $5,000. When those generated hefty returns, she made bigger deposits. On several occasions she was able to withdraw amounts ranging from $10,000 to $30,000.

But after investing more than $4.5 million of her own money over nearly four months, Courtney found her account was suddenly frozen. She was then issued a tax statement saying she owed nearly $500,000 in taxes before she could reactivate her account or access her funds.

Courtney said it seems obvious in hindsight that she should never have paid the tax bill. Because xtb-market and her mentor cut all communications with her after that, and the entire website disappeared just a few weeks later. Continue reading →