It was early October 2011, and I was on the treadmill checking email from my phone when I noticed several hundred new messages had arrived since I last looked at my Gmail inbox just 20 minutes earlier. I didn’t know it at the time, but my account was being used to beta test a private service now offered openly in the criminal underground that can be hired to create highly disruptive floods of junk email, text messages and phone calls.

Many businesses request some kind of confirmation from their bank whenever high-dollar transfers are initiated. These confirmations may be sent via text message or email, or the business may ask their bank to call them to verify requested transfers. The attack that hit my inbox was part of an offering that crooks can hire to flood each medium of communication, thereby preventing a targeted business from ever receiving or finding alerts from their bank.

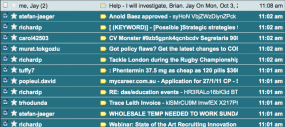

Shortly after the email barrage began, I fired off a note to Google‘s public relations folks, asking for advice and assistance. Thankfully, my phone line was not a subject of the attack, and I was able to communicate what I was seeing to Google’s team. They worked to fight the attack for the better part of that day, during which time my inbox received tens of thousands of emails, burying hundreds of legitimate emails in page after page of junk messages (in the screen shot above, the note to Google spokesman Jay Nancarrow is at the top of the junk message pile).

Shortly after the email barrage began, I fired off a note to Google‘s public relations folks, asking for advice and assistance. Thankfully, my phone line was not a subject of the attack, and I was able to communicate what I was seeing to Google’s team. They worked to fight the attack for the better part of that day, during which time my inbox received tens of thousands of emails, burying hundreds of legitimate emails in page after page of junk messages (in the screen shot above, the note to Google spokesman Jay Nancarrow is at the top of the junk message pile).

What was most surprising about these messages was that many of them contained fairly spammy subject lines that should have been easily caught by Google’s junk mail filters. Each junk message contained nothing but pages full of garbled letters and numbers; the text of each missive resembled an encrypted message.

Google’s engineers managed to block a majority of the junk messages after about six hours, but the company declined to talk about what caused the attack to succeed. It took many more hours to sift through the junk messages to fish out the ones I wanted.

“This isn’t about a hole in Gmail or an exploit — it’s more a matter of spam dynamics and what may be able to get through more easily under certain circumstances,” Nancarrow said. “As a result, we can’t provide specifics that could aid spammers in trying new campaigns.”

About a week after the attack, I was lurking on a relatively new cybercrime forum when I stumbled across an automated email flood service offered by one of the founders of the forum. The ad for this service included screenshots of a flooded Gmail inbox that looked exactly like the attack that hit my Gmail address.

The ad read, in part:

Used mostly in private for myself and now offered to the respected public.

Spam using bots, having decent SMTP accounts.

Doing email floods using bots. Complete randomization of the letter, so the user could not block the flood by the signatures.

Flooder is capable of the following functionality:

Huge wave of emails is being instantly sent to the victim. (depending on the server load and amount of emails to be flooded)

Delivery rate of 60-65% — depending on the SMTP servers.

Limit for flooding single email account on this server is 100,000 emails.

Plan – Children – 25,000 emails — $25

Plan – Medium – 50,000 emails — $40

Plan – Hard – 75,000 emails — $55

Plan – Monster – 100,000 emails — $70

The same seller has recently added some new offerings since debuting that email bomb service, including an SMS and call flooding system. The ads for those services read:

NEW!!! Call Flood and mass sending SMS service!

Flood the phone – a great way to block the work of any business associated with a telephone number into which the flood attack. The victim, during the whole period flood, receives countless number of incoming calls. When victim answer the phone, it makes system reset, and immediately call back. This happens all time the flood attack activated. This action completely block the phone, so nobody can get through on the phone of the victim.

Flooding one or more phone numbers (any operator, any country):

1 hour = $1.5 (per number)

1 day = $ 20 (per number)SMS mass sending:

100 SMS – $ 5

1000 SMS – $ 15

It’s alarming how easily and cheaply one can rent automated services capable of putting a small organization out of business for several days. A distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack on a company’s Web site would only increase the total cost of attack by about $50 a day, and there are a glut of DDoS services for hire these days.

If you run a small business and one day find yourself on the receiving end of one of these email, SMS and/or phone floods, I’d advise you to find a mobile phone that isn’t being blocked and alert your financial institution to be especially vigilant for suspicious transactions.

You were able to reach a human at google, and they actually responded and worked on your problem. ha ha ha, good one.

Thanks Mr. Krebs, this solves a mystery for me from last year!

I noticed this anomalous outbound activity starting around June of ’11, and continuing through September ’11 and finally tapering off earlier this year.

It was very interesting. The subjects appeared to have been grabbed from a mix of spam and ham subjects, like they were being scraped from the compromised accounts from which the malicious emails were emanating. However the body usually consisted of just blocks of alpha-numeric strings. No spam payload.

That got me worried. I started to think that it may be a covert form of data egress or possibly a funky C&C channel. However analysis of the “garbled text” did not suggest a simple cypher of English. IIRC there was an odd preponderance of Ms and Js but all other characters were pretty much flat, distribution wise.

Another observation was the compromised accounts were being used to target just a small (few dozen) set of addresses, which I thought indicated subversive communication, but a directed attack as described in your article now fits those observations rather well and clears up the mystery for me.

I ended up blocking a couple million of those things. Turns out that there were some consistencies in the message construction that made them stand out from the background and therefore not too difficult to block. Chilkat should ring a bell if we’re talking about the same thing…

SMS floods mentioned in Webroot blog

http://blog.webroot.com/2012/07/02/cyberciminals-launch-managed-sms-flooding-services/

I remember reading a story last year about Alexey Navalny’s e-mail being attacked in the same way as yours. He received several thousand messages to his Gmail account in one evening.

if you remember that is why verbal verification didn’t worked on tennessee bank’s case ($500k ACH)

verbal verification was the best solution but no more

Matt,

> matt

> July 18, 2012 at 1:52 am

> if you remember that is why verbal verification didn’t worked

> on tennessee bank’s case ($500k ACH)

> verbal verification was the best solution but no more

If the Tennessee story you are referring to is:

http://krebsonsecurity.com/2012/05/house-committee-to-probe-e-banking-heists/#more-15245

then I can’t see how you can use it as an example of TOOBA (totally out-of-band authentication) via the PSTN (public switched telephone network) being defeated. In this story the bank processed the fraudulent ACH batch without making the phone call to to the customer they had made in every previous instance.

Now, Brian Krebs *has* reported on incidents where the bad guys flooded the verification phone line with calls so the financial services institution could not reach the customer, and other incidents where the cyber-thieves managed to get the phone company to forward the verification phone line to one of their numbers. But this story did not mention either attack. What Brian wrote is that the bank simply did not follow it’s own security procedure.

As an aside, the FDIC knows this, but for some reason did not mention it in the 2011 FFIEC Supplemental Guidance. There is no need to to TOOBA every ACH. Cybercriminals can’t make off with your company’s money by sending an extra payment to one of your established payees. They have to add new payees (a new employee is a new payee). “Add Payee” is a *much* less common transaction than “Make A Payment”, so the customer hassle factor is reduced nearly to zero.

Compromised accounts were being used to target just a small (few dozen) set of addresses.

It makes the idea of maintaining secondary “authorised use only” email and phone accounts a must to protect against floods to the primarys killing the business.

Example: ensuring that those that need to have a secure line of contact can maintian access in the case of flooding. Moving clientel off the primary published contact number /address and onto another more private set.

If I ever experienced a DoS attack on one of my phones, I would forward it to 202- 324-3000 (main number of FBI HQ in Washington, DC)! I would hope that this would draw a prompt response from law enforcement .

Brian wrote:

> Many businesses request some kind of confirmation

> from their bank whenever high-dollar transfers are

> initiated.

Note that what is really important for fraud control purposes is that the addition of new payees (/first payment to a new payee) be subject to additional authentication. It’s difficult for me to see any added security value in, say, an IBM accountant having to answer a verifying phone call every time it makes a payment to, say, Intel for more X86 chips. Indeed, I would much rather have “heavy” security procedures reserved for “Add Payee” and “Account Control” (change of postal address/phone number/email address) transactions and have an ordinary userid+password suffice for logon and even payments of reasonable and customary sizes to established payees.

If a financial services institution puts its customers through the expense and hassle of using token cards, the thing to have them do with those cards is to touch-tone the OTPs they generate into the phone call that the F.I. makes to validate one of the truly security-critical transactions I list above, but only *after* the answer has been forced to listen to a verbal description of the transaction he/she is being asked to confirm. This use of OTP token cards defeats Internet session-hijacking and even telephone-hijacking (via call forwarding attacks).

Call *flooding* attacks are easily defeated. The F.I. has to default to not executing the addition of a payee / change of account control information without TOOBA (totally out-of-band authentication) transaction confirmation. If the fraudsters know that launching such attacks will not allow them to steal any money, they won’t do it.

There is also the point that under Section 4A of the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC), the F.I. is liable for an instance of fraud if it does not follow its own Security Procedure. Thus, F.I.s would be well advised to default to not processing ACHs that cannot be verified.

Gmails spam filters mystify me. The most blatant and obvious spam seems to be the easiest stuff to get through it.

I was also receiving the same exact small set of messages with the same exact attachment everyday for about 6 months.

Yet half the time I try to send someone a PDF it gets blocked by gmail.

Hello

I was wondering how do you get yourself into all these cybercrime forums? You always find something new to get yourself into and then you always make great articles. Dont the forum know that a security specialist is roaming the forum?

Hi Mack, thanks for the nice comment. I’m sure you’ll understand that it doesn’t behoove me to really answer your question openly. But let’s just say I don’t register under my real name (does anyone?).

Thanks for the reply! I am now going to start my journey looking for these MYSTERY forums and see what I can find.

haha. Why such a low comment rating? Me no get it O_O

To lurk like that.

You’d have to have a few dozen (or hundred) anon offshore email addresses and firefox with the easy to use TOR plugin.

It’s just not rocket science.

I realise you will not register under your own name (or IP).

But how do you find these forums in the first place?

Many of the forums link to others, or feature ads for other services.

.oO(A single bank account with hundreds of thousands bucks, just one published email address, only one widely known phone number… and a bank that’s just passing by your money if they don’t reach you, that’s obviously looking for trouble… Have restricted bank accounts with limitations to help ensure its use is within the holder’s guidelines and deposit (MMA/MMDA) or secondary/subaccounts just become old-fashioned?)

Additionally: Todays e-commerce even profiles your cats upchucking on the carpet but banks fail profiling peoples transfers?! Let’s give our money to Amazon then… 😉

Very interesting article. I would think there would be a temporary work around for a flood, thousands, of spam emails- a simple filter (option on the browser) that sorts incoming by previous contacts or new ones, for new ones maybe a simple resend request after a few minutes, the ones that didn’t repeat disguard, or as I recently got when resending from gmail, a simple capthcha.

One option banks don’t provide at this time is the customers’ ability to set some general rules, limits, on their accounts, and to make a change would require the additional authentication.

This is scary, I do however use a secure software intranet for my business called Bitrix24. I have a lot of information stored in there so its nice to know its a secured site but it always hits home when you read these articles.

Pardon my ignorance, but how does one flood a phone line? Use an automated dialer that redials as soon as the called party hangs up?

VOIP makes this a lot easier.

You dial and as soon as the PICKUP is heard, kill the connection and restart

For information about DoS phone attacks it’s making sense to google for DoS phone attack… 😐

” They worked to fight the attack for the better part of that day”… ah that utterly disgusts me. Your a great guy and do good work but you have the same account the rest of us do. But if you don’t have a platform such as this, Google treats you like less than dirt.

I find it more interesting that Google marked all that mail as “important”. The priority inbox feature, properly tuned, should allow you to sort out “important” mail like bank alerts above unimportant massive encrytped sets of data.

I wonder if your Priority Inbox trained on some encrypted mail?

so let me get this straight. someone pays this fellas a good amount of money to send SPAM? what do those who finance this scheme get in return? another entity that pays them to annoy people?? i mean no one (is there?) buys what they flooded you with right?

You’d be amazed at the number of people who would actually check out a link in spam. It could be as innocuous as advertising ‘per-click’ revenue that is their motivation.

On the other hand, as nagga pointed out, ‘hacktivism’ is definitely on the rise, so even if they don’t directly profit, the BG’s can still win.

The low cost of this is quite worrysome..

People spam cause there is profit in it, which doesn’t necessarely have to be financial profit.

If they can spam someones mail like Brian’s, and get him to dedicate time to sort them out, then it’s time he won’t be spending making their life harder. Sometimes value isn’t measured in money, but in effort and time.

Making something unavailable for a considerable amount of time causes disruption in the targeted companies’ sites and resources, which yields profit for their competitors or facilitates and masks security breaches on other sources they might not be looking at because they’re too busy dealing with whats obvious.

There’s profit in almost everything, it just depends what you use to measure the profit with 🙂

Interesting writeup. I just want to add that Google does respond (at least in my case) to complaints from their users even though I do not have a platform such as this. To elaborate, I duplicated my accounts which resulted to a suspension that was rescinded when I authenticated my ownership. This within the time frame mentioned in this article. I hope I am not very much off topic.

Now they know its working .

My relatives every time say that I am killing my time here at web, but I know I am

getting knowledge everyday by reading such pleasant content.

I liked the article. In retrospect, it doesn’t appear that surprising that such an attack would be used.

In other news, I find it ironic that a security expert has properly set up ssl for his web server and paid for a certificate from a trusted CA, and yet includes javascript and stylesheets from the unsecured version of his website.

I’m sure you know what is wrong with this picture — is there a reason for it?

Glad you liked the article. Is there some reason you need to read this blog using https?

Not particularly. The link I followed to get here happened to point to the https version of your website. I actually hadn’t realized that the website is primarily unsecured, and just happens also to be accessible via https. In retrospect, it doesn’t really matter for a blog (most blogs I can think of, anyway…), but the red https with a cross through it caught my attention.