Sometimes when a complex story takes us by surprise or knocks us back on our heels, it pays to revisit the events in a somewhat linear fashion. Here’s a brief timeline of what we know leading up to last week’s mass-hack, when hundreds of thousands of Microsoft Exchange Server systems got compromised and seeded with a powerful backdoor Trojan horse program.

When did Microsoft find out about attacks on previously unknown vulnerabilities in Exchange?

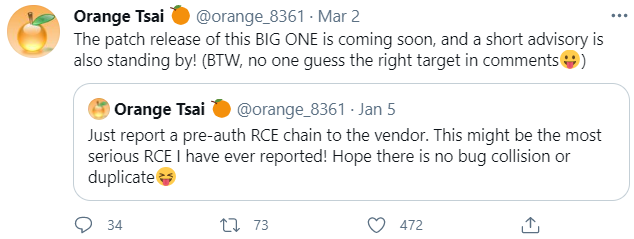

Pressed for a date when it first became aware of the problem, Microsoft told KrebsOnSecurity it was initially notified “in early January.” So far the earliest known report came on Jan. 5, from a principal security researcher for security testing firm DEVCORE who goes by the handle “Orange Tsai.” DEVCORE is credited with reporting two of the four Exchange flaws that Microsoft patched on Mar. 2.

Reston, Va.-based Volexity first identified attacks on the flaws on Jan. 6, and officially informed Microsoft about it on Feb. 2. Volexity now says it can see attack traffic going back to Jan. 3. Microsoft credits Volexity with reporting the same two Exchange flaws as DEVCORE.

Danish security firm Dubex says it first saw clients hit on Jan. 18, and reported their incident response findings to Microsoft on Jan. 27.

In a blog post on their discovery, Please Leave an Exploit After the Beep, Dubex said the victims it investigated in January had a “web shell” backdoor installed via the “unifying messaging” module, a component of Exchange that allows an organization to store voicemail and faxes along with emails, calendars, and contacts in users’ mailboxes.

“A unified messaging server also allows users access to voicemail features via smartphones, Microsoft Outlook and Outlook Web App,” Dubex wrote. “Most users and IT departments manage their voicemail separately from their email, and voicemail and email exist as separate inboxes hosted on separate servers. Unified Messaging offers an integrated store for all messages and access to content through the computer and the telephone.”

Dubex says Microsoft “escalated” their issue on Feb. 8, but never confirmed the zero-day with Dubex prior to the emergency patch plea on Mar. 2. “We never got a ‘real’ confirmation of the zero-day before the patch was released,” said Dubex’s Chief Technology Officer Jacob Herbst.

How long have the vulnerabilities exploited here been around?

On Mar. 2, Microsoft patched four flaws in Exchange Server 2013 through 2019. Exchange Server 2010 is no longer supported, but the software giant made a “defense in depth” exception and gave Server 2010 users a freebie patch, too. That means the vulnerabilities the attackers exploited have been in the Microsoft Exchange Server code base for more than ten years.

The timeline also means Microsoft had almost two months to push out the patch it ultimately shipped Mar. 2, or else help hundreds of thousands of Exchange customers mitigate the threat from this flaw before attackers started exploiting it indiscriminately.

Here’s a rough timeline as we know it so far:

- Jan. 5: DEVCORE alerts Microsoft of its findings.

- Jan. 6: Volexity spots attacks that use unknown vulnerabilities in Exchange.

- Jan. 8: DEVCORE reports Microsoft had reproduced the problems and verified their findings.

- Jan. 25: DEVCORE snags proxylogon.com, a domain now used to explain its vulnerability discovery process.

- Jan. 27: Dubex alerts Microsoft about attacks on a new Exchange flaw.

- Jan. 29: Trend Micro publishes a blog post about “China Chopper” web shells being dropped via Exchange flaws (but attributes cause as Exchange bug Microsoft patched in 2020)

- Feb. 2: Volexity warns Microsoft about active attacks on previously unknown Exchange vulnerabilities.

- Feb. 8: Microsoft tells Dubex it has “escalated” its report internally.

- Feb. 18: Microsoft confirms with DEVCORE a target date of Mar. 9 (tomorrow) for publishing security updates for the Exchange flaws. That is the second Tuesday of the month — a.k.a. “Patch Tuesday,” when Microsoft releases monthly security updates (and yes that means check back here tomorrow for the always riveting Patch Tuesday roundup).

- Feb. 26-27: Targeted exploitation gradually turns into a global mass-scan; attackers start rapidly backdooring vulnerable servers.

- Mar. 2: A week earlier than previously planned, Microsoft releases updates to plug 4 zero-day flaws in Exchange.

- Mar. 2: DEVCORE researcher Orange Tsai (noted for finding and reporting some fairly scary bugs in the past) jokes that nobody guessed Exchange as the source of his Jan. 5 tweet about “probably the most serious [remotely exploitable bug] I have ever reported.”

- Mar. 3: Tens of thousands of Exchange servers compromised worldwide, with thousands more servers getting freshly hacked each hour.

- Mar. 4: White House National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan tweets about importance of patching Exchange flaws, and how to detect if systems are already compromised.

- Mar. 5, 1:26 p.m. ET: In live briefing, White House press secretary Jen Psaki expresses concern over the size of the attack.

- Mar. 5, 4:07 p.m. ET: KrebsOnSecurity breaks the news that at least 30,000 organizations in the U.S. — and hundreds of thousands worldwide — now have backdoors installed.

- Mar. 5, 6:56 p.m. ET: Wired.com confirms the reported number of victims.

- Mar. 5, 8:04 p.m. ET: Former CISA head Chris Krebs tweets the real victim numbers “dwarf” what’s been reported publicly.

- Mar. 6: CISA says it is aware of “widespread domestic and international exploitation of Microsoft Exchange Server flaws.”

- Mar. 7: Security experts continue effort to notify victims, coordinate remediation, and remain vigilant for “Stage 2” of this attack (further exploitation of already-compromised servers).

- Mar. 9: Microsoft says 100,000 of 400,000 Exchange servers globally remain unpatched.

- Mar. 9: Microsoft “Patch Tuesday,” (the original publish date for the Exchange updates); Redmond patches 82 security holes in Windows and other software, including a zero-day vulnerability in its web browser software.

- Mar. 10: Working exploit for Exchange flaw published on Github and then removed by Microsoft, which owns the platform.

- Mar. 10: Security firm ESET reports at least 10 “advanced persistent threat” (APT) cybercrime and espionage groups have been exploiting the newly-exposed Exchange flaws for their own purposes.

- Mar. 12: Wall Street Journal, Financial Times, others report Microsoft is investigating how the exact exploit @OrangeTsai shared with Microsoft ended up being exploited publicly prior to Microsoft issuing its updates.

- Mar. 12: Microsoft says there are still 82,000 unpatched Exchange servers exposed. “Groups trying to take advantage of this vulnerability are attempting to implant ransomware and other malware that could interrupt business continuity.”

Update, 12:11 p.m. ET: Corrected link to Dubex site (it’s Dubex.dk). Also clarified timing of White House press statement expressing concern over the number of the Exchange Server compromises. Corrected date of Orange Tsai tweet.

Update, Mar. 10, 10:28 a.m. ET: Corrected date of proxylogon.com registration.

Updated, Mar. 14, 12:26 p.m. ET: Added entries in timeline for Mar. 9 through Mach. 12.

Brian, thanks for the timeline. I can also confirm the scan activity on Feb 26 based on our analysis of historical netflow data.

So will MS be punished?

Punished for having a flaw in their software? For building a patch and taking the time to verify it will not break systems before it is published? What exactly are you getting at?

Why didn’t Microsoft alert customers to a vulnerability once it was known that it was actively being exploited? No details needed to be released that would further enable attackers, but organizations should be made aware so they can decide to mitigate risk until a patch is available, or at least plan to patch as soon as one is available.

If this was a software flaw in automobiles that hurt 30,000+ individuals in one month, you can be certain that the manufacturer would be held liable via thousands of lawsuits for damages and would be subpoenaed before Congress to explain their actions. So yes they should be punished for having a flaw in their software. It is about time code writers, programmers and software companies face liability for the damage their products do. No other industry gets a free pass like that. Not only that, but via their license agreements, the software vendor retains all ownership of the software, so they can’t claim now it’s not their responsibility.

>Punished for having a flaw in their software?

Exactly.

Sure. If software companies or authors would be held liable for flaws in their software, half of them would stop writing software, because they would not be able to pay damages. The other half would increase their prices, to be able to have enough financial resources to pay for future damages. Every freeware and open source software would disappear.

Is that really what you want? No more free software, and paying twice as much for all paid software?

It’s over 30 years since Microsoft released its first products. Decades go by and over and over their software has been hacked, trashed, compromised, and violated. We’re all supposed to sit on the edge of our chairs and wait for the next compromise and hope it gets patched lickety-split. Why should anyone want to apologize for or defend Microsoft? They are a multi-billion dollar worldwide company. If they have made a product too complex to manage or secure how is that our fault (except when we buy it)? This stuff they make is, has been, and always will be swiss cheese.

Every software is swiss cheese if an attacker is given enough time to look at it and find flaws. Microsoft is targeted heavily because they are used predominantly in the marketplace and attackers know it is a good place to focus their efforts.

Not true. AFAIK OSS licenses always declare no liability for whatsoever damage. And it makes sense, you can check the code yourself (or hire an expert) before deploying. It’s also the same reason why closed source will always contain easter eggs like this.

Which no one actually does. Heartbleed, Shellshock, Poodle . . . open source software is no more secure than closed source software. This is an industry problem.

definitely not. For what? For having built in a secret backdoor on demand of certain state “services”?

MS got rewarded in the market by watching their stock jump 3% yesterday. Go figure.

EULA laughs and laughs

Bingo! Can’t use it unless you waive legal action.

Their punishment could be to finish debugging and getting rid of security holes in windows 3.11 wfw before they can sell another version of anything…

i just remember how much fun faults with win95a,b,c,d were after the hype about its greatness.

they never get any product completely finished before pushing another buggy product down our throat.

depending on their business model will be our civilization’s downfall.

In this age of artificial intelligence/machine learn when they want to use it to cure disease, why have these companies not invested in their AI in spotting unknown code vulnerabilities? No eating of their own dog foods?

> why are companies not using their AI / ML?

Perhaps because deep down they know their AI / ML is weak?

In this case AI wasn’t needed. Microsoft was notified in early January of this critical vulnerability that was already being exploited, and didn’t respond with patches for 2 months. That’s just negligence.

You can easily argue that:

a) Develop a remediation across systems going back a decade.

b) Develop and test patchest for email systems used for millions of messages daily.

c) Delay announcing until the above was ready, because to do so could have led to the mass infections occuring in January instead of late Feb/early March.

Not easy.

“In this case AI wasn’t needed. Microsoft was notified in early January of this critical vulnerability that was already being exploited, and didn’t respond with patches for 2 months. That’s just negligence.”

But then again, I suspect you’d also be complaining about “Microsoft’s negligence” if they pushed out software updates/patches with little testing as quickly as they could that managed to crash/trash/brick business Exchange servers across the world.

Like it or not. Microsoft ain’t some small rinky, dinky software company that can push out software patches to the thousands of users of its software quickly. It takes some time. Yeah, in cases like this it isn’t a good thing. But there you are and here we are.

Every hacker is hacker and should be investigated.

Whats b hats all black and criminals .

Justice is for all if criminal do bad things against other criminal the criminal shouldb be punished for crimes

Please try.

Still haven’t heard why this didn’t affect Exchange Online? anyone know why?

There are no details about it, so we can only speculate. From technical perspective, the reason is that frontends in Exchange Online cloud are inaccessible anonymously – there is no classic forms-based authentication interface, instead they are redirecting clients without valid session to authentication servers (IdP). And I’d bet there are also WAFs attached to the request flow (WAF with appropriate rules can prevent this attack). And even if the attack could be feasible on Exchange Online, the attackers rather chose not to shoot on Microsoft as there is much bigger chance that the attack will be spotted and analyzed soon.

My guess is that attackers actively avoided attacking Microsoft. The sooner you attack the primary vendor the sooner the vendor will discover and remediate any bug.

It’s better to start w/ a targeted attack on a smaller target.

That’s separate from whether or not the online instance itself was vulnerable (I can imagine the implementation / infrastructure using more readonly file systems in a way that would mitigate pieces).

But, all of this is speculation.

Exchange Online isn’t affected because there isn’t an ECP.

Although ECP is now in phase-out stage and replaced by modern 365 management interface, Exchange Online still has ECP accessible at URL https://outlook.office.com/ecp/ , however it is slightly different in multi-tenant environment.

If you have a 0day why would you use it on the company making the product, they are more likely to detect and remediate it quickly.

Get more mileage from using it against other companies.

The proxylogon.com link Brian provides also has a timeline. It contains some DEVCOR-related details the very curious may want to inspect.

Could we get some details on how the 30k (or 60k) number of “backdoors installed” was arrived at? What is SPECIFICALLY seen on these 30k systems that guarantees a backdoor “web script” was installed? I’m also interested whether this number is CONFIRMED hacks with compromised assets, or just doorknob-rattling? Nobody seems to be able to answer any of these non-media questions. Thanks.

Let’s say you run the security operations at a major ISP or hosting company. You can say we’re seeing signs that X # or X percent of vulnerable hosts are compromised. Then other big providers start sharing numbers. That’s how it adds up. That’s why it’s not exact. Because you don’t know what you don’t know. But you can infer a lot from what you do know.

Does that make sense?

It’s way more than 30k or 60k! Someone put up a new exchange server facing the Internet and in 25 hours had 5 separate exploit attempts with drops of the remote shell. No active connections back out but that’s crazy and shows the sheer volume of the number of scans taking place out there in the wild!

Not necessarily. Just because every Exchange server is poked doesn’t mean every server is vulnerable. It’s likely that some configurations don’t have the attack vector enabled (even if unpatched), while others do. Without specifics (likely forthcoming) we can only speculate.

Kudos for the clarification without going so far down the rabbit hole of “Unknown Knowns”, and “Known Unknowns,” and “Things that we know we don’t know we know,” until we’re either staring at the Zen God of War, or Donald Rumsfeld. 🙂

Clarity is always so helpful. Thank you.

That’s exactly my complaint. There is absolutely no *list* anywhere from anyone as to how the 30,000 number was developed, let alone the “hundreds of thousands globally” claim that is being floated around with zero evidence.

I call bullcrap.

Now they’re saying the zero-days were in place for the last ten years. In that case, while it may seem likely that any number of groups could have found and used those vulnerabilities over that period of time, the more likely scenario is that only a few – possibly even only one, HAFNIUM – knew of the flaws and were actively exploiting them. This makes it highly unlikely that every organization in the world with an Exchange server was actually compromised.

It’s also unlikely that in the month between Microsoft’s detection and issuing the patch that enough groups would have latched onto the vulnerabilities and developed an effective compromise enabling them to hit “hundreds of thousands” of systems.

This isn’t a “worm” which automatically wanders around and infects every system it sees. An automated attack could approximate that capability, but it seems unlikely that these zero-days were spread around long enough and exploited long enough and indiscriminately enough to justify the hype.

Specifically, this also includes China. If HAFNIUM is in fact a Chinese actor (and the attribution of these attacks to it is considered weak by some infosec researchers), and if HAFNIUM was the initial developer of the compromise, we then have to consider whether one Chinese actor was capable of executing all of the alleged compromises world-wide.

We then have to consider why a Chinese actor – especially one that is supposed to be state-sponsored – would have conducted such a scatter-shot campaign which would inevitably be detected and result in negative geopolitical consequences.

Moon of Alabama blog brings up this precise point in this post: Is China Hacking Random Servers To Put Itself Into A Bad Light? – https://www.moonofalabama.org/2021/03/is-china-hacking-random-servers-to-put-itself-into-a-bad-light.html

I suspect that the number of actual breaches don’t amount to anywhere near the 30,000 number, let alone the “hundreds of thousands” being bandied about. I further suspect that this incident is being exploited by both the US software industry and infosec industry, and especially the US government, to further an anti-China geopolitical agenda.

In particular, Microsoft would appear to be in a tough place. Four serious zero-day bugs in one of their flagship server products is being used to compromise allegedly “hundreds of thousands” of organizations world-wide. Concentrating on “China” is one way to divert attention from Microsoft’s massive security failure.

As far as the infosec community goes, this sort of thing raises the question: How in the hell are any of you still employed?

See this comment:

https://krebsonsecurity.com/2021/03/a-basic-timeline-of-the-exchange-mass-hack/#comment-529328

I agree. I don’t buy any of it.

I’ve looked through all the CVE’s and every article, and security podcast I know and NOWHERE are there any details about A) what to look for, B) exactly what it does, c) how to protect the server / LAN.

If there is shell planted on a system – I will be able to see it, or every port scanner tool on the planet is now irrelevant.

If there is malware on the LAN – via SNORT I should be able to see it or sniffing packets in/out of network is now irrelevant.

There should be SOME way SysAdmin’s can know if they have been compromised, but this info is nowhere to be found. We are supposed to just believe and be afraid.

So, I follow the money – who stands to benefit the mo$t from this? You know exactly who – M$.

They don’t make any money of the exchange 2010, 2013, etc. servers. They make TONS OF $$ on O365, which just so happens to be unaffected.

Right.

Ok, I wish there was an ‘edit’ option on this forum :-/

https://proxylogon.com/ explains the hack – only place I’ve seen a logical explanation.

Issue is OWA (which I figured…what other than IIS) and the bad traffic is undetectable unless you have a layer 7 filtering firewall (possibly) because it’s over an encrypted channel (443).

Web shell malware is software deployed by a hacker, usually on a victim’s web server. It can be used to execute arbitrary system commands, which are commonly sent over HTTP or HTTPS.

So they this is exploiting IIS via OWA over 443 so as to be undetected.

What exactly means “webshell”?

A classic webshell like C99?

Or a back-connect “Webshell” that does somehow

connects to outside C&C’s.

µ$ leaves us standing in the rain

by not giving precise information to the public.

This is a poor job done.

https://www.fireeye.com/blog/threat-research/2013/08/breaking-down-the-china-chopper-web-shell-part-i.html

And yet they talk about splitting up Facebook etc. when the real danger to our Society is the Microsoft Monopoly.

…and need I mention that this hack is actually GOOD news for Microsoft. Customers will be queuing to get into the 365 Cloud for lack of a secure onsite alternative (naturally this will all be slipped under the CFO’ pen as “optimisations”, “cost reductions”, “ROI” and a series of other fancy words which serve to hide one simple fact: no IT manager wants to be responsible for Microsoft’ fuck ups. So throw it into the Cloud and shake your coats. Microsoft says thank you.

Some wisdom from the grey beards: place your Exchange servers always behind Unix MTAs. This is a long established practice which regularly saves your day.

How exactly does placing it behind a UNIX MTA prevent the exploit that used a system which allows phones and mobile clients to access email over an SSL web port?

https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/exchange/plan-and-deploy/deployment-ref/network-ports?view=exchserver-2019#network-ports-required-for-clients-and-services

I run my own postfix/dovecot mail server so all I know about Exchange is what I can dig up online. I see no mandatory web access. There are Outlook clients for Android and IOS.

I purposely don’t set up web email on my server. Just another thing to get hacked. Less is more and all that jazz. When I used a hosted service I was hacked via Roundcube. Like I said I don’t do web email but that doesn’t stop the hosting service from providing it.

I haven’t looked up the CVEs but to my recollection the security issues with postfix and dovecot have been in OpenSSL.

It’s a general advice meant to deal with Exchange’s problems. But you’re right about the current security issue, i.e. an Unix MTA doesn’t protect the Exchange’s client or web access. That should be done by VPN, so the Exchange server isn’t exposed directly to the Internet in any way. Exchange has a history of many problems, not just security-wise, and MS isn’t the fastest in providing patches. Unix MTAs are more robust in general and patches are issued much quicker in case of newly detected security issues (plus some other benefits).

To protect OWA use a VPN or a reverse proxy with pre-auth. The important point is to make sure that Exchange isn’t reachable directly.

Protect OWA with VPN, you might as well disable OWA and run a full email client.

How do we know that it was the Chinese government behind this? I’m not doubting it; I am just curious how such a well organized effort can leave enough fingerprints that we know who it was. In general, how is it possible to trace hacking back to a particular group or country? This would make a good article for the future. What do the experts look at? How does it all work? How sure can they be?

…here’s one example from few years ago…

…the fbi is on the hop points with nsl’s…

…so yes, we know who they are…

https://www.fireeye.com/content/dam/fireeye-www/services/pdfs/mandiant-apt1-report.pdf

Yes, I saw that report when it came out. Is it fair to assume that they have since learned not to use Chinese IP addresses linked to public records of their military? I was thinking more along the lines of the malware itself or other indicators that are less obvious. Perhaps there are no other indications of their identity, but they don’t bother to hide who they are, so it doesn’t matter.

…the malware itself has tell tale signs that usually trace to an author, like encryption methods for blocks of code they try to obfuscate…

…of course they can always buy it from someone else, but usually don’t…

…the compiler leaves hints as well – unicode, strings in ada pro, etc., identify other signs of the author…

…the inside baseball is Tools, Techniques. Procedures or TTP…

…poker players call it Tells…

Thanks. That explanation is helpful.

Thanks to “Security Vet” & “Peter.” A set of issues related to “attribution” is the under-appreciated effect it has on Cyber Insurance coverage. Many policies have either complete exclusions for “acts of state” or nations, or as in the Mondelez litigation “acts of war, declared or undeclared.”

Even where coverage exists, it is qualified and subject to almost unknown “Sub limits” buried in the deepest recesses of nearly incomprehensible language which often render the coverage almost worthless.

…even the insurance underwriters know the nation states are hacking us…

..sure, the criminals are too, but nation state action is at least as much…

..and in any case, the defenses are more or less the same…

It sounds like there are many levels of analysis from the exploits, to the motives, the effort (or lack thereof) to obfuscate, the effect it has on victims and nations… Wow! The most important part of this whole saga is that there are no repercussions for the nation-state or its hackers. I fear that we will see many more of these stories in months and years to come.

…the russians (soviets before that) and the chinese have been attacking us for at least 30 years…

…read the cuckoos egg for some historical perspective…

What if you put this in line with the access to the Exchange source code by the adversaries around the Solarwinds case?

Chris, I agree there was some access to code involved here, or perhaps an insider @ MS. When looking at some log examples I saw IPs allocated to the MSN network performing the same access to the exploited URLs as the attackers. Why would MS need to access someone’s on-prem Exchange server using this proxy method? All very curious. There’s more going on here than we know about right now.

Precisely. This is only the first example of what is to come.

Microsoft was hit hard by the Solarwinds hack and they had to undergo a massive internally cover-up operation, for the idea that the world’s biggest enterprise software company has been breached down to source code would be equivalent to the downfall of Civilisation.

I am not joking. The world runs on (outdated) Microsoft technology. And now the bad guys own the source code.

What massive cover up? Microsoft very publicly detailed that their code had been viewed during the SolarWinds attack. They were a lot more public about those details that most companies are when they get compromised.

I’m not saying Microsoft is some beacon of virtue, but you’re saying there was a massive cover up when in fact they’ve been fairly transparent about exactly how the Solarwinds attack impacted them.

Brian, it seems they call themselves DEVCORE

https://proxylogon.com/

Thanks, Andy. I fixed that early on but never hit save on the changes. Should be corrected now.

It is almost like these company IT people have never heard of an email gateway. Complex communications systems don’t need to be directly on the internet.

…outlook anywhere and OWA changed the rules…

Nice work Orange Tea. I just can’t help but wonder if Pisakey really expressed concern, or just read what she was told to read and why she didn’t mention China. Too bad for her authors that it wasn’t Russia.

The proxylogon.com domain was registered on Jan 25, not Jan 11 as noted in the article.

Thanks Brian, this year starts with a bang of highly sufiticated attacks. Has everyone here participated in an incident remediation related hacks.

Just a minor correction: it’s Jen Psaki, not Paski.

I find it strange that in public comment, Microsoft studiously ignores the key contribution of DEVCORE and Orange Tsai:

“Microsoft would like to thank our industry colleagues at Volexity and Dubex for reporting different parts of the attack chain and their collaboration in the investigation. Volexity has also published a blog post with their analysis. It is this level of proactive communication and intelligence sharing that allows the community to come together to get ahead of attacks before they spread and improve security for all.”

https://www.microsoft.com/security/blog/2021/03/02/hafnium-targeting-exchange-servers/

They credit DEVCORE in 2 of the four Exchange flaws fixed last Tuesday:

https://msrc.microsoft.com/update-guide/vulnerability/CVE-2021-26855

https://msrc.microsoft.com/update-guide/vulnerability/CVE-2021-27065

We’re moving to O365 over the next couple of months. I was somewhat against the idea because I always liked the full control you get with on-prem servers in general. However, if MS is going to have insanely horrible bugs like THIS one, cloud-based is suddenly sounding a whole lot better to me. I don’t want to be blamed for a breach of our network. I have enough things to worry about already.

Yes, I know MS would like nothing more than us paying them for 365 mail hosting, but if it’s mutually beneficial, I don’t see a problem with that.

Pardon my silly question, moving to O365 might seem fine when addressing problems of the sort, however, doesn’t this then introduce other security issues that come with adopting a Cloud solution? How much better is this as a trade-off or alternative?

This is a “pre-auth” exploit?! Why does the unified messaging server allow any pre-auth activity? Why would any server, anywhere, of any kind, allow pre-auth activity?

pre-auth means “before authentication”.

It means the exploit can be executed w/o having credentials on the system.

Usually most of a system’s guts aren’t available to users w/o logging in. (The more of a system that’s exposed, the more things that can be attacked.)

Thus you’ll often see attacks as “privilege escalation” — being logged in and being able to become a more powerful user.

I’m curious how the exploit leaked out? According to the timeline, it is impossible to do reverse engineering for the patch. Since this is a vulnerability that has existed for ten years, it is unlikely that a hacker discovered it at the same time.

At a certain point the easiest way to figure these attacks out is to leave a honeypot online and watch someone attack it.

Certainly at a certain point dozens of entities were able to see the attack and understand how it worked.

Some attackers will work hard to cover their tracks (hiding evidence of how they attacked). But it doesn’t sound like this attacker bothered. (And such efforts generally only work if there isn’t another system that collects logs in between. — WAF – Web Application Firewalls are an example, although they can be additional attack vectors.)

…i’m unburdened by any evidence – but my educated guess is that reverse engineering on other patches showed this vuln and was kept quiet since it had pre-auth access to mailbox contents…

…in any case that’s what i would do given the same info…

The update in Volexity’s article pointed out that the attack occurred on January 3, earlier than DEVCORE reported to Microsoft. This is the strange part of the timeline. I agree that honeypot is one of the most possible causes of exploit leakage, provided that DEVCORE is not the attacker nor the source of the data leakage.

Mass scanning activity on our servers (from various IPs using different user agents) began on 2/24. One of these agents was “WhatWeb/0.5.5”, a scanning tool, so global exploit began two days earlier than assumed.

1. Timelines. The first DETECTION was Jan 2, not necessarily the first attack. The vulnerability has been around since 2010 that we know of.

2. Approach. The attack was used quietly “below the radar” on selected targets. There was no mass attack until a couple of months after discovery, when stealth no longer matters. The mass attack nature of today does not invalidate the China claim.

3. According to the timeline “Jan. 29: Trend Micro publishes a blog post about “China Chopper” web shells being dropped via Exchange flaws”. Plenty of time for bad actors to investigate further or set up diagnostic honeypots.

4. Attribution. Tricky, and only accept it from credible, professionally staffed groups. Some actors emulate others to cause confusion, some have stolen code from others. To most of us, it isn’t important compared to patching and IoC searching, except to understand who is being targeted by whom. Right now we know it’s all of us, because it’s turned into a wild fire.

The attackers exploited have been in the Microsoft Exchange Server code base for more than ten years. Great work Microsoft. Asleep at the switch again, nothing new here.

…… Interesting smoke screen… Ol’ Billy was an inspiration to all of us… How does one become an expert in microbiology, while being one of the greatest programmers…. How does one own a patent to the alleged pandemic….. A dropout of Harvard, a person who has openly said the world’s population needs to be reduced 12-15% and laughed about it. How does someone like this get hacked? C’mon now people, y’all can not be that naive. Like I said before, interesting smoke screen. Food for thought, how does one proclaim to be against AI in 2015, but yet be all for AI in 2020??? Perhaps being one of the biggest investors in CRISPR might open eyes wide shut

Microsoft switched years ago from actually having professionals test their code to an Artificial intelligence based approach. It has done wonders for their stock price, but QC went out the window years ago.

Tankyou for the support

Here are the Articles for hafnium attack information:

https://www.microsoft.com/security/blog/2021/03/02/hafnium-targeting-exchange-servers/

https://www.msspalert.com/cybersecurity-news/microsoft-exchange-hafnium-attack-timeline/

https://www.splunk.com/en_us/blog/security/detecting-hafnium-exchange-server-zero-day-activity-in-sp…

https://www.stellarinfo.com/blog/recover-microsoft-exchange-server-after-hafnium-attack/