Millions of U.S. government employees and contractors have been issued a secure smart ID card that enables physical access to buildings and controlled spaces, and provides access to government computer networks and systems at the cardholder’s appropriate security level. But many government employees aren’t issued an approved card reader device that lets them use these cards at home or remotely, and so turn to low-cost readers they find online. What could go wrong? Here’s one example.

A sample Common Access Card (CAC). Image: Cac.mil.

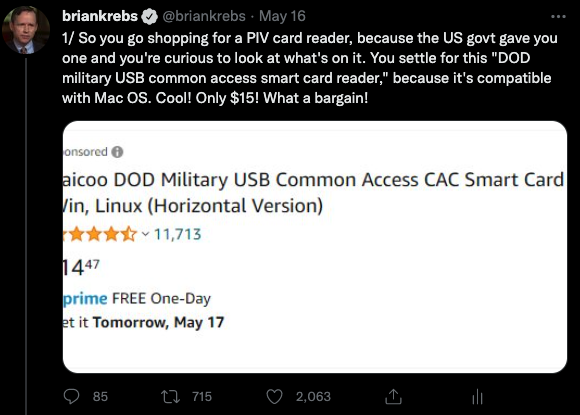

KrebsOnSecurity recently heard from a reader — we’ll call him “Mark” because he wasn’t authorized to speak to the press — who works in IT for a major government defense contractor and was issued a Personal Identity Verification (PIV) government smart card designed for civilian employees. Not having a smart card reader at home and lacking any obvious guidance from his co-workers on how to get one, Mark opted to purchase a $15 reader from Amazon that said it was made to handle U.S. government smart cards.

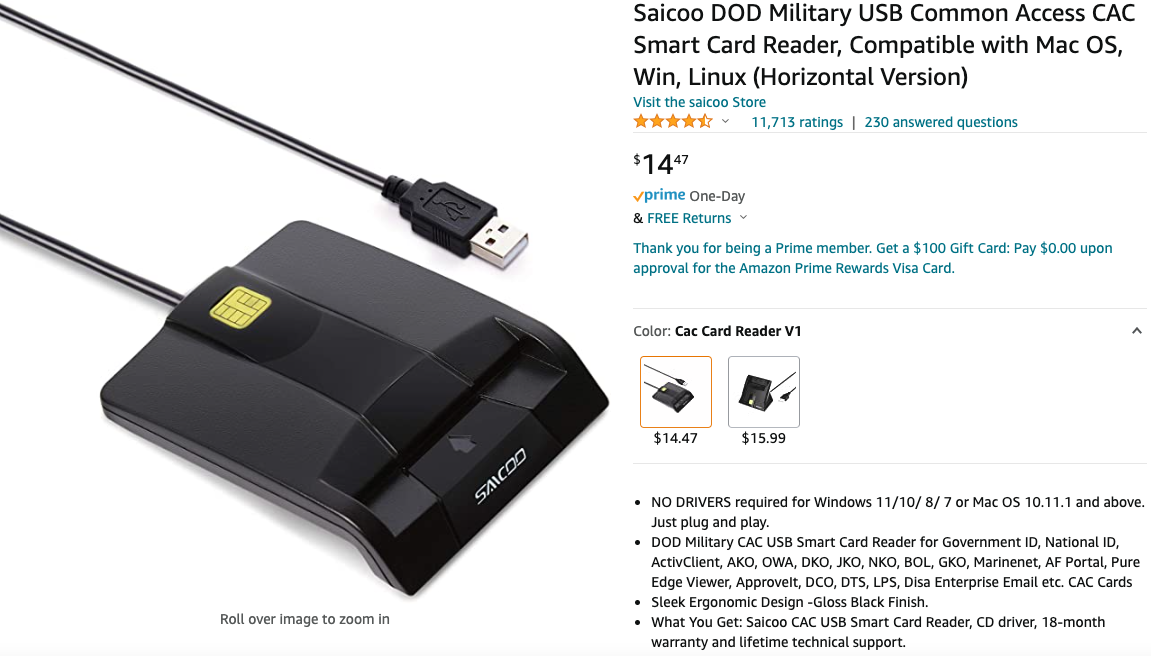

The USB-based device Mark settled on is the first result that currently comes up one when searches on Amazon.com for “PIV card reader.” The card reader Mark bought was sold by a company called Saicoo, whose sponsored Amazon listing advertises a “DOD Military USB Common Access Card (CAC) Reader” and has more than 11,700 mostly positive ratings.

The Common Access Card (CAC) is the standard identification for active duty uniformed service personnel, selected reserve, DoD civilian employees, and eligible contractor personnel. It is the principal card used to enable physical access to buildings and controlled spaces, and provides access to DoD computer networks and systems.

Mark said when he received the reader and plugged it into his Windows 10 PC, the operating system complained that the device’s hardware drivers weren’t functioning properly. Windows suggested consulting the vendor’s website for newer drivers.

The Saicoo smart card reader that Mark purchased. Image: Amazon.com

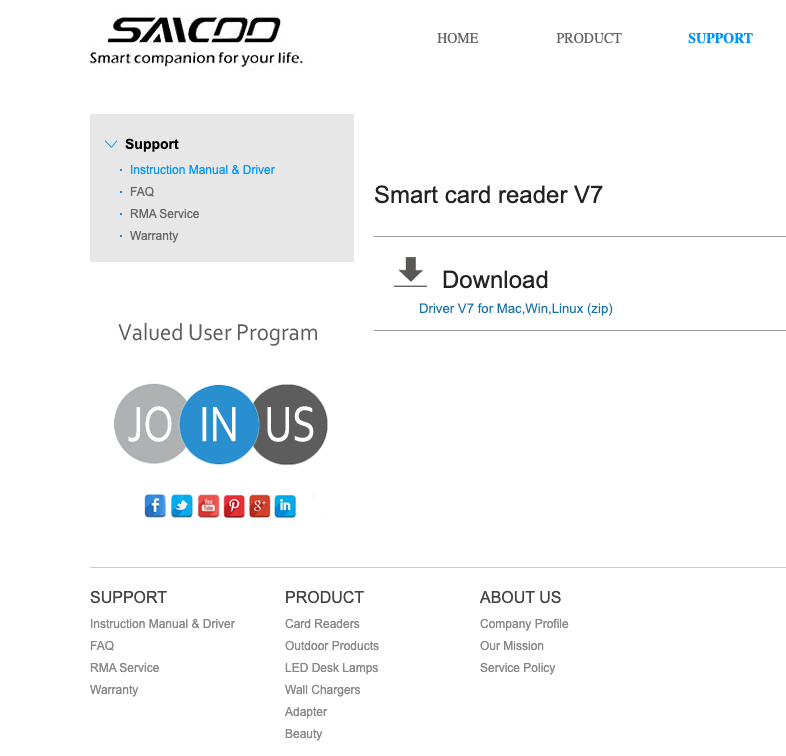

So Mark went to the website mentioned on Saicoo’s packaging and found a ZIP file containing drivers for Linux, Mac OS and Windows:

Image: Saicoo

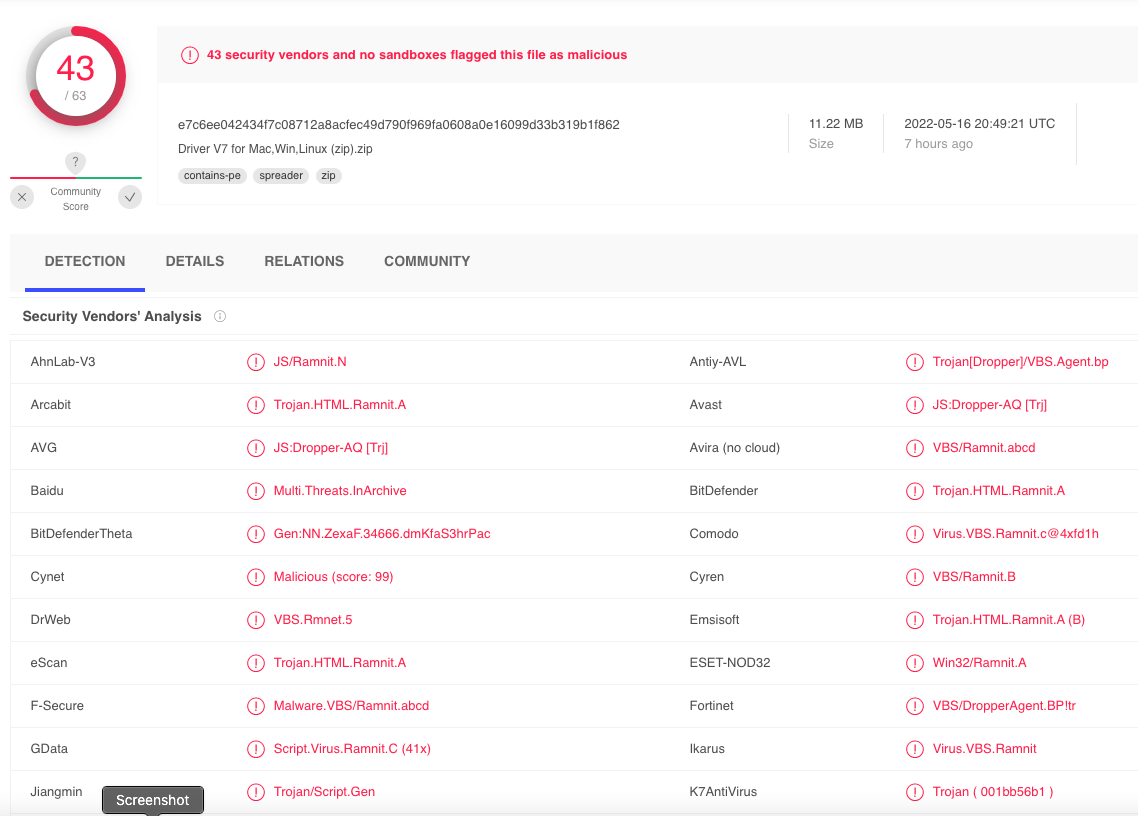

Out of an abundance of caution, Mark submitted Saicoo’s drivers file to Virustotal.com, which simultaneously scans any shared files with more than five dozen antivirus and security products. Virustotal reported that some 43 different security tools detected the Saicoo drivers as malicious. The consensus seems to be that the ZIP file currently harbors a malware threat known as Ramnit, a fairly common but dangerous trojan horse that spreads by appending itself to other files.

Ramnit is a well-known and older threat — first surfacing more than a decade ago — but it has evolved over the years and is still employed in more sophisticated data exfiltration attacks. Amazon said in a written statement that it was investigating the reports.

“Seems like a potentially significant national security risk, considering that many end users might have elevated clearance levels who are using PIV cards for secure access,” Mark said.

Mark said he contacted Saicoo about their website serving up malware, and received a response saying the company’s newest hardware did not require any additional drivers. He said Saicoo did not address his concern that the driver package on its website was bundled with malware.

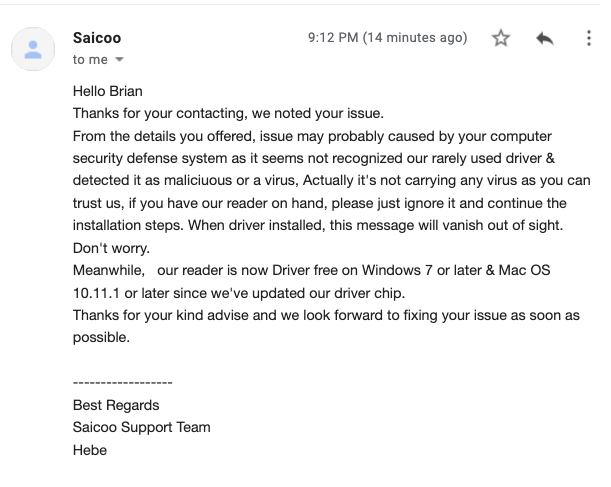

In response to KrebsOnSecurity’s request for comment, Saicoo sent a somewhat less reassuring reply.

“From the details you offered, issue may probably caused by your computer security defense system as it seems not recognized our rarely used driver & detected it as malicious or a virus,” Saicoo’s support team wrote in an email.

“Actually, it’s not carrying any virus as you can trust us, if you have our reader on hand, please just ignore it and continue the installation steps,” the message continued. “When driver installed, this message will vanish out of sight. Don’t worry.”

Saicoo’s response to KrebsOnSecurity.

The trouble with Saicoo’s apparently infected drivers may be little more than a case of a technology company having their site hacked and responding poorly. Will Dormann, a vulnerability analyst at CERT/CC, wrote on Twitter that the executable files (.exe) in the Saicoo drivers ZIP file were not altered by the Ramnit malware — only the included HTML files.

Dormann said it’s bad enough that searching for device drivers online is one of the riskiest activities one can undertake online.

“Doing a web search for drivers is a VERY dangerous (in terms of legit/malicious hit ratio) search to perform, based on results of any time I’ve tried to do it,” Dormann added. “Combine that with the apparent due diligence of the vendor outlined here, and well, it ain’t a pretty picture.”

But by all accounts, the potential attack surface here is enormous, as many federal employees clearly will purchase these readers from a myriad of online vendors when the need arises. Saicoo’s product listings, for example, are replete with comments from customers who self-state that they work at a federal agency (and several who reported problems installing drivers).

A thread about Mark’s experience on Twitter generated a strong response from some of my followers, many of whom apparently work for the U.S. government in some capacity and have government-issued CAC or PIV cards.

Two things emerged clearly from that conversation. The first was general confusion about whether the U.S. government has any sort of list of approved vendors. It does. The General Services Administration (GSA), the agency which handles procurement for federal civilian agencies, maintains a list of approved card reader vendors at idmanagement.gov (Saicoo is not on that list). [Thanks to @MetaBiometrics and @shugenja for the link!]

The other theme that ran through the Twitter discussion was the reality that many people find buying off-the-shelf readers more expedient than going through the GSA’s official procurement process, whether it’s because they were never issued one or the reader they were using simply no longer worked or was lost and they needed another one quickly.

“Almost every officer and NCO [non-commissioned officer] I know in the Reserve Component has a CAC reader they bought because they had to get to their DOD email at home and they’ve never been issued a laptop or a CAC reader,” said David Dixon, an Army veteran and author who lives in Northern Virginia. “When your boss tells you to check your email at home and you’re in the National Guard and you live 2 hours from the nearest [non-classified military network installation], what do you think is going to happen?”

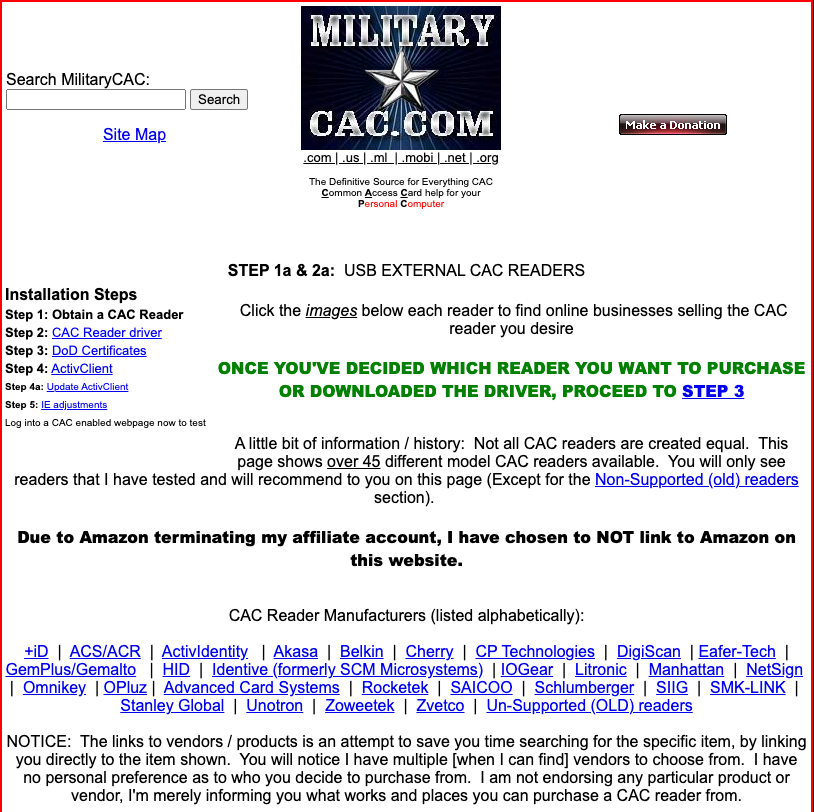

Interestingly, anyone asking on Twitter about how to navigate purchasing the right smart card reader and getting it all to work properly is invariably steered toward militarycac.com. The website is maintained by Michael Danberry, a decorated and retired Army veteran who launched the site in 2008 (its text and link-heavy design very much takes one back to that era of the Internet and webpages in general). His site has even been officially recommended by the Army (PDF). Mark shared emails showing Saicoo itself recommends militarycac.com.

Image: Militarycac.com.

“The Army Reserve started using CAC logon in May 2006,” Danberry wrote on his “About” page. “I [once again] became the ‘Go to guy’ for my Army Reserve Center and Minnesota. I thought Why stop there? I could use my website and knowledge of CAC and share it with you.”

Danberry did not respond to requests for an interview — no doubt because he’s busy doing tech support for the federal government. The friendly message on Danberry’s voicemail instructs support-needing callers to leave detailed information about the issue they’re having with CAC/PIV card readers.

Dixon said Danberry has “done more to keep the Army running and connected than all the G6s [Army Chief Information Officers] put together.”

In many ways, Mr. Danberry is the equivalent of that little known software developer whose tiny open-sourced code project ends up becoming widely adopted and eventually folded into the fabric of the Internet. I wonder if he ever imagined 15 years ago that his website would one day become “critical infrastructure” for Uncle Sam?

This is the tip of the iceberg. When I was at USCIS, the SolarWinds machine was slowing our network down so much that we had to disconnect it. The Russians were looking at everything, especially congressional email. It’s a wonder that the Russians don’t cause the US to nuke itself.

If you worry about your cac reader, tremble in fear when you realize your router was made in China!

By an unknown brand that specifies it’s for US government use in broken English?

Quoting the article:

“In many ways, Mr. Danberry is the equivalent of that little known software developer whose tiny open-sourced code project ends up becoming widely adopted and eventually folded into the fabric of the Internet. I wonder if he ever imagined 15 years ago that his website would one day become “critical infrastructure” for Uncle Sam?”

A graphic interpretation of this can be seen here:

https://imgs.xkcd.com/comics/dependency.png

To me, buying equipment that is in any way involved with security is a risky deal. The organization should have provided the user with either a qualified list of equipment/providers OR the actual equipment, along with said list. It should be possible for the end-user to procure another unit for home use. Especially with the work at home scenario from the past two years.

HA! The image is spot on. Its the absolute truth with that site too.

I should have posted this link instead:

https://xkcd.com/2347/

It’s more than a picture.

Amazon is full of Chinese garbage so this story doesn’t surprise me in the least.

PIV is always rape

Militarycac.com really is In many ways, critical infrastructure. “In many ways, Mr. Danberry is the equivalent of that little known software developer whose tiny open-sourced code project ends up becoming widely adopted and eventually folded into the fabric of the Internet. I wonder if he ever imagined 15 years ago that his website would one day become “critical infrastructure” for Uncle Sam?” – honest to god, I don’t know anyone in the reserves who does NOT use his site in any branch of service. Speaking from personal experience, Army National Guard, Army Reserve, Coast Guard, and Navy.

Active Duty, too!!

I went onto Amazon and searched for PIV Reader and asked the question if it was approved for US government use. I had five people reply back within 24 hours stating that it was even though both readers I viewed are not approved by the GSA. Also, the people that replied stated I work for (insert name here) agency which made it that more crazy. People just don’t get phishing.

Has anyone else actually looked at the actual malware involved in this? The stuff won’t even run, there’s no realistic infection vector.

When you download the zip off the company’s website (e7c6ee042434f7c08712a8acfec49d790f969fa0608a0e16099d33b319b1f862), it extracts into a whole folder with a legitimate installer file and supporting documentation. The installer exes are all clean. The infected part is the html help files for the Android application. When you view the source code of those html files, you’ll see a VBScript at the end of each file which, if executed, would drop Ramnit, a 10 year old heavily-signatured trojan.

The problem is there are no circumstances under which this VBScript would be executed. It’s commented out. So even if the user went to install the Android app, encountered a problem, went to open the documentation, the malware still won’t install even if the user opens the infected HTML file in their web browser. Nevermind the fact this is a silly infection vector even if the code weren’t commented out; if the attacker were serious about spreading their trojan they could have just replaced Setup.exe or Autorun.exe with the trojan.

In any case, this is hardly a sophisticated nation-state level attack against people with government CAC cards.

It probably exploited some idiotic vulnerability in IE6, and those files were probably originally rolled up on someone’s computer in China running a pirated copy of WinXP so it merrily propagated itself into those files at some point, and no one since has bothered to ask what the weird comments at the end of the code are for (or they’re using a WYSIWYG editor and don’t even see them, thus they remain as the files are copied/reused as templates/etc.

Good that you looked at it before jumping off, but that kind of sidesteps the point you’re begging a question toward – just how easily could it have been a legitimate effort given the clumsiness and apparent lack of protocol or common sense by the end-user, in this case a privileged secrets custodian duly employed by national security? No doubt this wasn’t the hack of the century and wasn’t going to be, but just how unprepared and hamfisted is the larger operational security if this is a single recent public example that non-SCI public even come to know about. It’s a black box from the outside, from the inside this is a single glimpse and it’s obviously not pretty.

Indeed. I guess that is why the “C” stands for compartmentalized. These are personal computers. No end user would even be allowed to install anything, let alone drivers. You can’t fix stupid users. Best you can do is limit their access to the “privileged secrets”. Which is not on any network that would be accessible from the internet by personal computers.

My Saicoo reader worked without needing additional drivers. WIndows used driver “Microsoft Usbccid Smartcard Reader (WUDF)” v. 10.0.22000.653. Out of curiosity, why did you link to PACS readers for the supposedly approved list of CAC readers? PACS is for door access, not for reading the PIV cert on your CAC.