Some financial institutions are now offering so-called “cardless ATM” transactions that allow customers to withdraw cash using nothing more than their mobile phones. But as the following story illustrates, this new technology also creates an avenue for thieves to quickly and quietly convert stolen customer bank account usernames and passwords into cold hard cash. Worse still, fraudulent cardless ATM withdrawals may prove more difficult for customers to dispute because they place the victim at the scene of the crime.

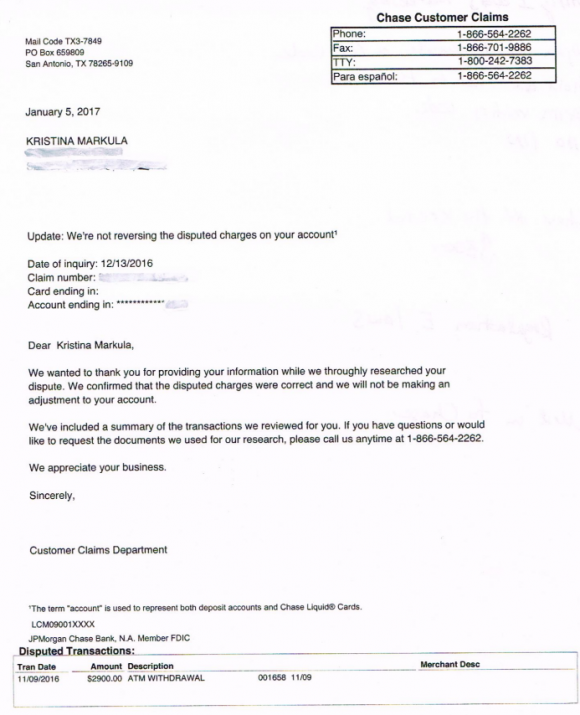

A portion of the third rejection letter that Markula received from Chase about her $2,900 fraud claim.

San Francisco resident Kristina Markula told KrebsOnSecurity that it wasn’t until shortly after a vacation in Cancun, Mexico in early November 2016 that she first learned that Chase Bank even offered cardless ATM access. Markula said that while she was still in Mexico she tried to view her bank balance using a Chase app on her smartphone, but that the app blocked her from accessing her account.

Markula said she thought at the time that Chase had blocked her from using the app because the request came from an unusual location. After all, she didn’t have an international calling or data plan and was trying to access the account via Wi-Fi at her hotel in Mexico.

Upon returning to the United States, Markula called the number on the back of her card and was told she needed to visit the nearest Chase bank branch and present two forms of identification. At a Chase branch in San Francisco, she handed the teller a California driver’s license and her passport. The branch manager told her that someone had used her Chase online banking username and password to add a new mobile phone number to her account, and then move $2,900 from her savings to her checking account.

The manager told Markula that whoever made the change then requested that a new mobile device be added to the account, and changed the contact email address for the account. Very soon after, that same new mobile device was used to withdraw $2,900 in cash from her checking account at the Chase Bank ATM in Pembroke Pines, Fla.

A handful of U.S. banks, including Chase, have deployed ATMs that are capable of dispensing cash without requiring an ATM card. In the case of Chase ATMs, the customer approaches the cash machine with a smart phone that is already associated with a Chase account. Associating an account with the mobile app merely requires the customer to supply the app with their online banking username and password.

Users then tell the Chase app how much they want to withdraw, and the app creates a unique 7-digit code that needs to be entered at the Chase ATM (instead of numeric code, some banks offering cardless ATM withdrawals will have the app display a QR code that needs to be read by a scanner on the ATM). Assuming the code checks out, the machine dispenses the requested cash and the transaction is complete. At no time is the Chase customer asked to enter his or her 4-digit ATM card PIN.

Most financial institutions will limit traditional ATM customers to withdrawing $300-$600 per transaction, but some banks have set cardless transaction limits at much higher amounts under certain circumstances. For example, at the time Markula’s fraud occurred, the limit was set at $3,000 for withdrawals during normal bank business hours and made at Chase ATMs located at Chase branches.

Markula said the bank employees helped her close the account and file a claim to dispute the withdrawal. She said the teller and the bank manager reviewed her passport and confirmed that the disputed transaction took place during the time between which her passport was stamped by U.S. and Mexican immigration authorities. However, Markula said Chase repeatedly denied her claims.

“We wanted to thank you for providing your information while we thoroughly researched your dispute,” Chase’s customer claims department wrote in the third rejection letter sent to Markula, dated January 5, 2017. “We confirmed that the disputed charges were correct and we will not be making an adjustment to your account.”

Markula said she was dumbfounded by the rejection letter because the last time she spoke with a fraud claims manager at Chase, the manager told her that the transaction had all of the hallmarks of an account takeover.

“I’m pretty frustrated at the process so far,” said Markula, who shared with this author a detailed timeline of events before and after the disputed transaction. “Not captured in this timeline are the countless phone calls to the fraud department which is routed overseas. The time it takes to reach someone and poor communication seems designed to make one want to give up.”

KrebsOnSecurity contacted Chase today about Markula’s case. Chase spokesman Mike Fusco said Markula’s rejection letter was incorrect, and that further investigation revealed she had been victimized by a group of a half-dozen fraudsters who were caught using the above-described technique to empty out Chase bank accounts.

Fusco forwarded this author a link to a Fox28 story about six men from Miami, Fla. who were arrested late last year in Columbus, Ohio in connection with what authorities there called a “multi-state crime spree” targeting Chase accounts.

“We escalated it and reviewed her issue and determined she did have fraud on her account,” Fusco said. “We’re reimbursing her and we’re really sorry. This small pilot we ran allowed a limited number of customers to access cash at Chase ATMs without a card. During the pilot we detected some fraudulent activity where a group of people were able to go online and change the customer’s information and get the one-time access code, and we immediately notified the authorities.”

Chase declined to say how many like Markula were victimized by this gang. Unfortunately, somehow Chase neglected to notify victims, as Markula’s case shows.

“It makes you wonder how many other people didn’t dispute the charges,” she said. “Thankfully, I don’t give up easily.”

Fusco said Chase had made changes to better detect these types of fraudulent transactions going forward, and that it had lowered the withdrawal limit for these types of transactions — although for security reasons Fusco declined to say what the new limit was.

Fusco also said the bank’s system should have sent out an email alert to the original email on file in the event that the email on the account is changed, but Markula said she’s confident no such email ever landed in her inbox.

Avivah Litan, a fraud analyst at Gartner Inc., says many banks see mobile authentication as the way of the future for online banking and ATM transactions. She said most banks would love to be able to move away from physical bank cards, which often need to be replaced several times a year in response to data breaches at various retailers.

“A lot of banks see cardless transactions as a great way to reduce fraud and speed up transactions, but not many are offering it yet as a feature to customers,” Litan said.

Litan said Markula’s case echoes the spike in fraud that some banks saw after Apple debuted its Apple Pay platform. Many banks chose to adopt Apple Pay without also beefing up security around how they validate new customers and new mobile devices. As a result, this allowed fraudsters to take stolen credit card numbers and expiration dates — data that previously was only good for fraudulent online transactions — tie those cards to iPhones, and use the phones to commit card fraud at brick-and-mortar stores that accepted Apple Pay.

“Identity proofing remains the weakest point in mobile banking,” Litan said. “Asking for the customer’s username and password to on-board a new mobile device isn’t enough.”

Litan said Chase should require customers who wish to conduct cardless ATM transactions to enter their PIN in addition to the one-time code. But she said even that was not enough.

Litan said Chase should have flagged the transaction as highly suspicious from the get-go, given that the fraudsters accessed her account from a new location, changed her contact email address, added a new device and withdrew just under the daily maximum — all in a very short span of time.

“ATM transactions should have much stronger fraud controls because consumers don’t have as strong protections as they do with other transactions,” Litan said. “If a customer’s card is used fraudulently at a retailer, for example, the consumer is protected by Visa and MasterCard’s zero liability rule, and they can generally expect to get their money back. But when you withdraw cash from an ATM, you’re not protected by those rules. It’s down to Regulation E and your bank’s policies.”

Under the Federal Regulation E, if a retail banking customer reports fraud, the bank must investigate the first statement of the activity plus 60 days from the date the statement was mailed by the financial institution. Unless the institution can prove the transaction wasn’t fraud, it must reimburse the consumer. However, any activity that takes place outside of the aforementioned timeframe carries unlimited liability to the consumer, as the financial institution may have been able to prevent the loss had it been reported in a timely manner.

Fusco added that consumers should beware of phishing scams, and consider asking their financial institution to secure their accounts with a special passphrase or code that needs to be supplied when authenticating with the bank over the telephone (a precaution I have long advised).

Also, if your bank offers two-step or two-factor authentication — such as the requirement to send a text-message with a one-time code to your mobile device if someone attempts to log in from an unknown device or location — please take advantage of that feature. Twofactorauth.org has a list of banks that offer this additional security feature.

Also, as the Regulation E paragraph I hope makes clear, do not count on your bank to block fraudulent transfers, and remember that ultimately you are responsible for spotting and reporting fraudulent transactions.

Litan said she won’t be surprised if this incident gives more banks pause about moving to cardless ATM transactions.

“This is the first case I’m aware of in the United States where this type of fraud has been an issue,” she said. “I’m guessing this will slow the banks down a bit in adopting the technology because they’ll see now how easy it is for criminals to take advantage of it.”

Update, Jan. 6, 9:44 a.m. ET: Looks like Chase could have learned from the experience of NatWest, a big bank in the U.K. that experienced much the same fraud five years ago after enabling a cardless “get cash” feature.

Is there info on how the fraudsters got the user’s user and pass to get into their account?

Well if they were able to change the email and phone associated with the account, that would be trivial. Request the username over email, reset the password, and get the validation code that Chase sends over email or text/phone. Changing the email and phone is also trivial if they can socially engineer the CSAs at Chase.

Here is an idea, not saying this is how it happened, but just an idea:

Mobile apps are very promiscuous. They share information with each other like crazy. When users install an App they consent to things they are not aware of, or they are, but chose to be lazy. The app ask you to allow access to your files, photos, microphone, camera, etc. etc. Then why are we be surprised certain key elements leak out? If the app is a nice an honest app like Facebook (cough, cough, insert “Yeah right” here), they will inform you what rights you are giving up. But if you install the “The Daily Yoga Routine” or “DYI for dummies” that you got from who knows where, then even more bets are off. My phone is encrypted and has all kids of authentication and security measures, but I still do not trust it to conduct financial transactions. There are just too many unknowns to me. I am not the kind of person that jumps out of the bridge, just because everybody else is doing it. That is just the way I chose to protect myself for the moment.

200% agree…

If you don’t know what you’re doing on a computerized device, you shouldn’t have or be using one. same thing goes for cars, guns, microwaves, etc. etc.

I’d agree, but there’s no getting that toothpaste back into the tube now.

Please don’t victim-blame. Provide education, not blame.

The criminal is at fault, not the victim.

Simple. I watched Live 2 RS Programming coding experts violate and breach accounts several years back. I was touting as almost bullet proof and 2 step authorization as’ insurance’. they cracked it in < 2 minutes. Some of the avenues into your box, are from an unsuspecting source and once I, they can extract all they want to

It’s like Chase’s left hand doesn’t know what it’s right hand is doing, and at times appears nefarious in it’s dealings with customers. If you hadn’t contacted them Brian, would Markula’s case have been resolved in her favor?

“Chase declined to say how many like Markula were victimized by this gang. Unfortunately, somehow Chase neglected to notify victims, as Markula’s case shows.”

The ‘somehow’, as my experience with Chase after a local ATM fraud with a card shows, is always somehow in Chase’s favor. They will try to stick the victim with it unless you can prove you weren’t there, with something like Google tracking or an instant response by yourself from a notification. How many others have been stuck with this fraud by Chase and didn’t have a Brian Kerbs to propose uncomfortable and pointed questions?

Makes one wonder who the real crooks are…

BofA had 2 factor auth before any other bank I came across. I’m they’re as flawed as every other bank but the 2 factor auth on their app was effective and would have prevented this.

Well, it seems like quite a hole in their security if they allow such changes to be made without authorization. Say I want to change the phone to a new number – sure, as long as I type a OTP that I received on the old number. Otherwise – please visit the nearest branch. Overall it looks that the only thing that keeps fraudsters from getting Chase’s customers cash is a password. That certainly should not be the case. Certainly not for such big amounts of money.

Another reason why financial criminals get away with victims’ passwords and pins is via public WiFi.

Avoid transacting using public WiFi because third parties, especially criminals might be monitoring your online activities.

The multi-state arrests report provided to the author was from December 5, 2016. The denial of fraudulent transactions in Chase’s response to Kristina Markula was dated January 5, 2017. That means Chase knew about the fraudsters a full month before declaring there were no fraudulent transactions on Kristina’s account. Then Chase conveniently claims the letter was in error once confronted by KrebsOnSecurity. Clearly Chase’s integrity is right up there with Wells Fargo. Glad I do not bank with them!

Great article Brian! And thanks for standing up for your friend. I was poised to cancel my Chase account until I read the part of the story where they conceded their error, apologized and refunded the money after you intervened.

You really have to be so so careful with security. We have been careful about security for many years in terms of locking the house, holding bag close and keeping belongs close by. But I think that cyber security in gerneral is overlooked on the whole. The amount of companies that I here about that are getting hacked, or fraudulant behaviour occurs ect. Its scarry stuff, people need to wake up and get a grip of their security.

It’s a good thing that I use a local bank and online access is protected by 2 factor authentication (can’t give more specifics what that is for my bank) and that I have alerts set for any login attempt.