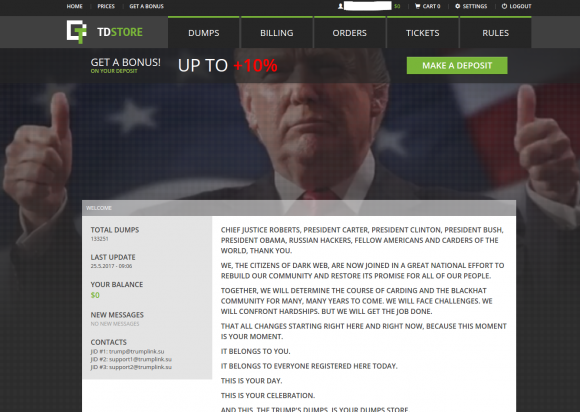

It’s not uncommon for crooks who peddle stolen credit cards to seize on iconic American figures of wealth and power in the digital advertisements for their shops that run incessantly on various cybercrime forums. Exhibit A: McDumpals, a hugely popular carding site that borrows the Ronald McDonald character from McDonald’s and caters to bulk buyers. Exhibit B: Uncle Sam’s dumps shop, which wants YOU! to buy American. Today, we’ll look at an up-and-coming stolen credit card shop called Trump’s-Dumps, which invokes the 45th president’s likeness and promises to make credit card fraud great again.

One reason thieves who sell stolen credit cards like to use popular American figures in their ads may be that a majority of their clients are people in the United States. Very often we’re talking about street gang members in the U.S. who use their purchased “dumps” — the data copied from the magnetic stripes of cards swiped through hacked point-of-sale systems — to make counterfeit copies of the cards. They then use the counterfeit cards in big-box stores to buy merchandise that they can easily resell for cash, such as gift cards, Apple devices and gaming systems.

When most of your clientele are street thugs based in the United States, it helps to leverage a brand strongly associated with America because you gain instant brand recognition with your customers. Also, a great many of these card shops are run by Russians and hosted at networks based in Russia, and the abuse of trademarks closely tied to the U.S. economy is a not-so-subtle “screw you” to American consumers.

In some cases, the guys running these card shops are openly hostile to the United States. Loyal readers will recall the stolen credit card shop “Rescator” — which was the main source of cards stolen in the Target, Home Depot and Sally Beauty breaches (among others) — was tied to a Ukrainian man who authored a nationalistic, pro-Russian blog which railed against the United States and called for the collapse of the American economy.

In deconstructing the 2014 breach at Sally Beauty, I interviewed a former Sally Beauty corporate network administrator who said the customer credit cards being stolen with the help of card-stealing malware installed on Sally Beauty point-of-sale devices that phoned home to a domain called “anti-us-proxy-war[dot]com.”

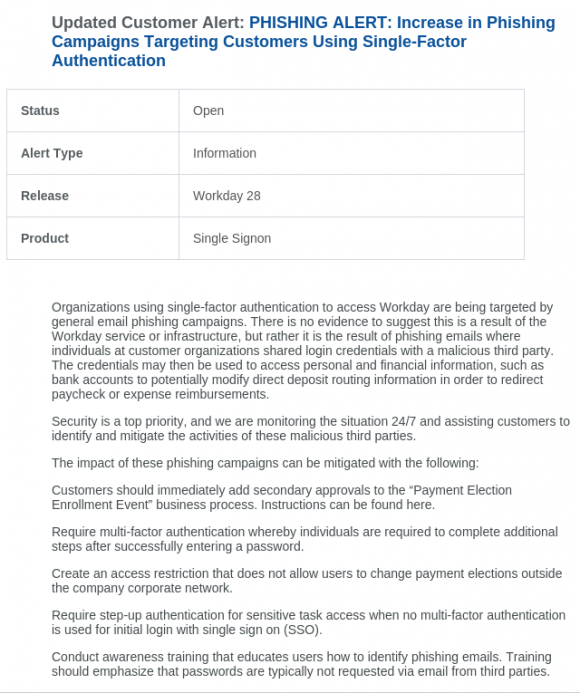

Trump’s Dumps currently advertises more than 133,000 stolen credit and debit card dumps for sale. The prices range from just under $10 worth of Bitcoin to more than $40 in Bitcoin, depending on which bank issued the card, the cardholder’s geographic location, and whether the cards are tied to premium, prepaid, business or executive accounts.

A “state of the dumps” address on Trump’s-Dumps.

In April 2017 I received an anonymous tip from a reader who said he’d figured out that just by changing a single number in the Web address when accessing his recent medical claim at MolinaHealthcare.com he could then view any and all other patient claims.

In April 2017 I received an anonymous tip from a reader who said he’d figured out that just by changing a single number in the Web address when accessing his recent medical claim at MolinaHealthcare.com he could then view any and all other patient claims.