Some financial institutions are now offering so-called “cardless ATM” transactions that allow customers to withdraw cash using nothing more than their mobile phones. But as the following story illustrates, this new technology also creates an avenue for thieves to quickly and quietly convert stolen customer bank account usernames and passwords into cold hard cash. Worse still, fraudulent cardless ATM withdrawals may prove more difficult for customers to dispute because they place the victim at the scene of the crime.

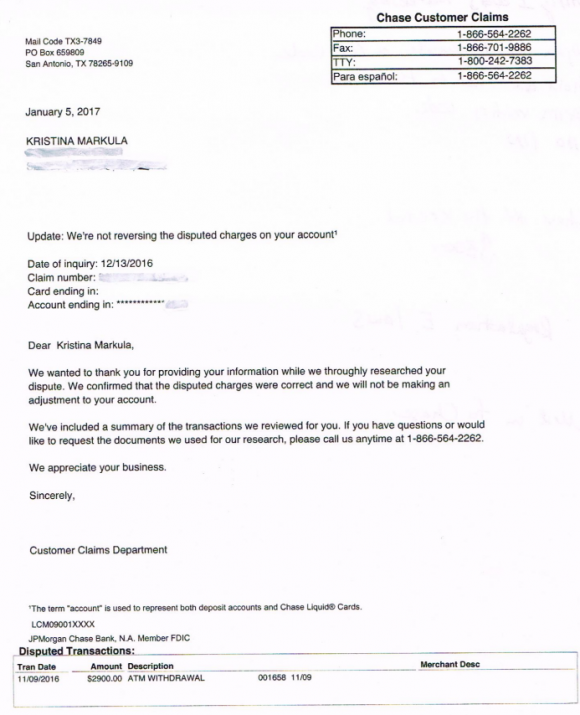

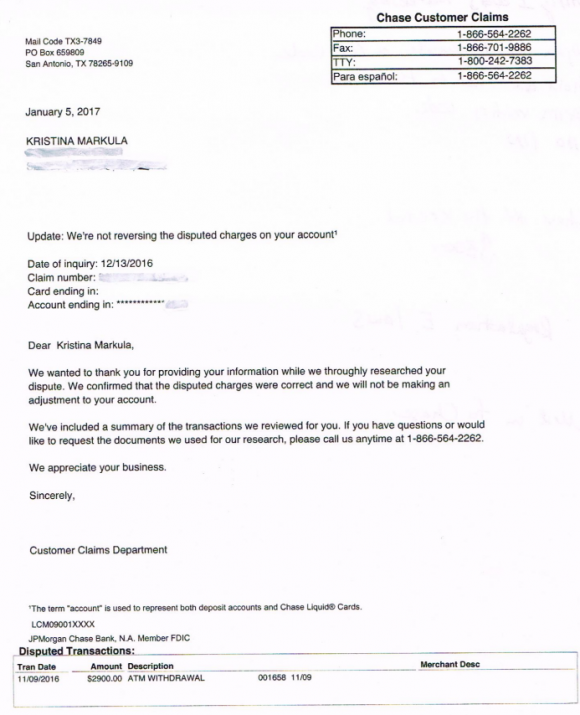

A portion of the third rejection letter that Markula received from Chase about her $2,900 fraud claim.

San Francisco resident Kristina Markula told KrebsOnSecurity that it wasn’t until shortly after a vacation in Cancun, Mexico in early November 2016 that she first learned that Chase Bank even offered cardless ATM access. Markula said that while she was still in Mexico she tried to view her bank balance using a Chase app on her smartphone, but that the app blocked her from accessing her account.

Markula said she thought at the time that Chase had blocked her from using the app because the request came from an unusual location. After all, she didn’t have an international calling or data plan and was trying to access the account via Wi-Fi at her hotel in Mexico.

Upon returning to the United States, Markula called the number on the back of her card and was told she needed to visit the nearest Chase bank branch and present two forms of identification. At a Chase branch in San Francisco, she handed the teller a California driver’s license and her passport. The branch manager told her that someone had used her Chase online banking username and password to add a new mobile phone number to her account, and then move $2,900 from her savings to her checking account.

The manager told Markula that whoever made the change then requested that a new mobile device be added to the account, and changed the contact email address for the account. Very soon after, that same new mobile device was used to withdraw $2,900 in cash from her checking account at the Chase Bank ATM in Pembroke Pines, Fla.

A handful of U.S. banks, including Chase, have deployed ATMs that are capable of dispensing cash without requiring an ATM card. In the case of Chase ATMs, the customer approaches the cash machine with a smart phone that is already associated with a Chase account. Associating an account with the mobile app merely requires the customer to supply the app with their online banking username and password.

Users then tell the Chase app how much they want to withdraw, and the app creates a unique 7-digit code that needs to be entered at the Chase ATM (instead of numeric code, some banks offering cardless ATM withdrawals will have the app display a QR code that needs to be read by a scanner on the ATM). Assuming the code checks out, the machine dispenses the requested cash and the transaction is complete. At no time is the Chase customer asked to enter his or her 4-digit ATM card PIN.

Most financial institutions will limit traditional ATM customers to withdrawing $300-$600 per transaction, but some banks have set cardless transaction limits at much higher amounts under certain circumstances. For example, at the time Markula’s fraud occurred, the limit was set at $3,000 for withdrawals during normal bank business hours and made at Chase ATMs located at Chase branches.

Markula said the bank employees helped her close the account and file a claim to dispute the withdrawal. She said the teller and the bank manager reviewed her passport and confirmed that the disputed transaction took place during the time between which her passport was stamped by U.S. and Mexican immigration authorities. However, Markula said Chase repeatedly denied her claims.

“We wanted to thank you for providing your information while we thoroughly researched your dispute,” Chase’s customer claims department wrote in the third rejection letter sent to Markula, dated January 5, 2017. “We confirmed that the disputed charges were correct and we will not be making an adjustment to your account.”

Markula said she was dumbfounded by the rejection letter because the last time she spoke with a fraud claims manager at Chase, the manager told her that the transaction had all of the hallmarks of an account takeover.

“I’m pretty frustrated at the process so far,” said Markula, who shared with this author a detailed timeline of events before and after the disputed transaction. “Not captured in this timeline are the countless phone calls to the fraud department which is routed overseas. The time it takes to reach someone and poor communication seems designed to make one want to give up.”

KrebsOnSecurity contacted Chase today about Markula’s case. Chase spokesman Mike Fusco said Markula’s rejection letter was incorrect, and that further investigation revealed she had been victimized by a group of a half-dozen fraudsters who were caught using the above-described technique to empty out Chase bank accounts.

Fusco forwarded this author a link to a Fox28 story about six men from Miami, Fla. who were arrested late last year in Columbus, Ohio in connection with what authorities there called a “multi-state crime spree” targeting Chase accounts. Continue reading →

Microsoft’s batch includes updates for Windows, Office and Microsoft Edge (Redmond’s replacement for Internet Explorer). Also interesting is that January 2017 is the last month Microsoft plans to publish individual bulletins for each patch. From now on, some of the data points currently in the individual updates will be lumped into a “Security Updates Guide” published with each Patch Tuesday.

Microsoft’s batch includes updates for Windows, Office and Microsoft Edge (Redmond’s replacement for Internet Explorer). Also interesting is that January 2017 is the last month Microsoft plans to publish individual bulletins for each patch. From now on, some of the data points currently in the individual updates will be lumped into a “Security Updates Guide” published with each Patch Tuesday.

“There are some fairly simple, immutable truths that each of us should keep in mind, truths that apply equally to political parties, organizations and corporations alike:

“There are some fairly simple, immutable truths that each of us should keep in mind, truths that apply equally to political parties, organizations and corporations alike:

But there is another reason for my reticence: Both of these stories are so politically fraught that to write about them means signing up for gobs of vitriolic hate mail from readers who assume I have some political axe to grind no matter what I publish on the matter.

But there is another reason for my reticence: Both of these stories are so politically fraught that to write about them means signing up for gobs of vitriolic hate mail from readers who assume I have some political axe to grind no matter what I publish on the matter.

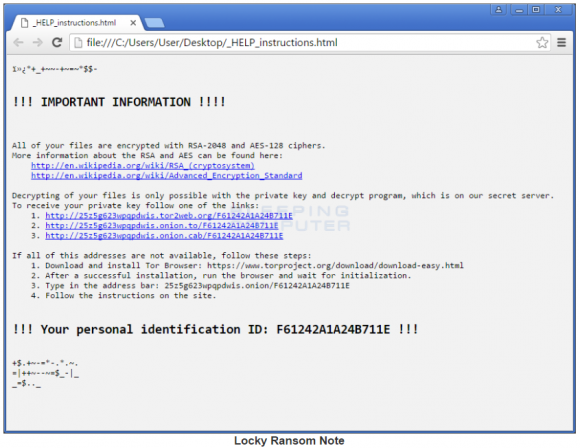

Villain: You MUST pay the ransom!

Villain: You MUST pay the ransom!