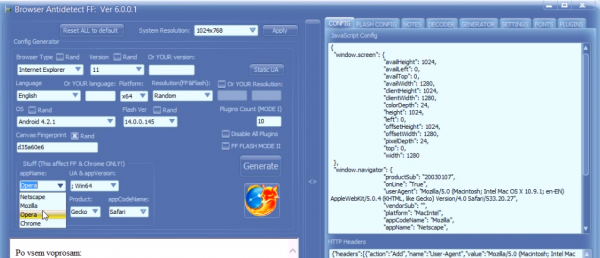

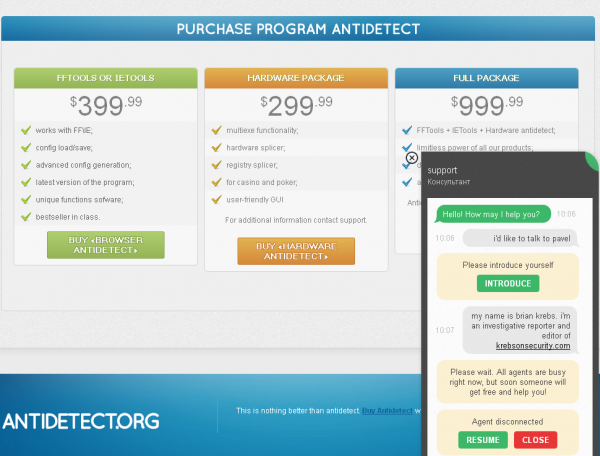

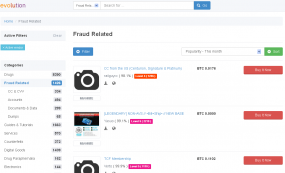

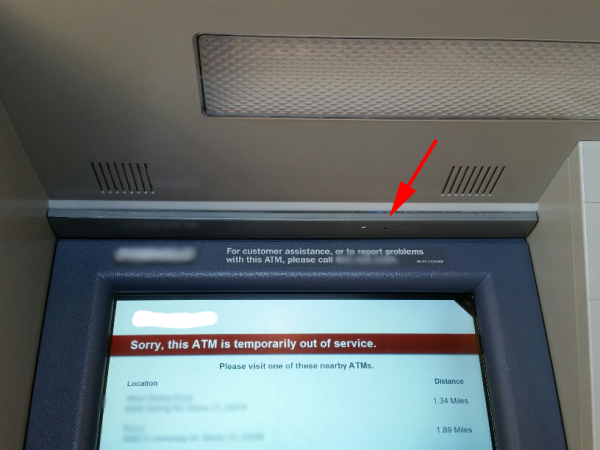

Earlier this month I wrote about Antidetect, a commercial tool designed to help thieves evade fraud detection schemes employed by many e-commerce companies. That piece walked readers through a sales video for Antidetect showing the software being used to buy products online with stolen credit cards. Today, we’ll take a closer look at clues to a possible real-life identity of this tool’s creator.

The author of Antidetect uses the nickname “Byte Catcher,” and advertises on several crime forums that he can be reached at the ICQ address 737084, and at the jabber instant messaging handles “byte.catcher@xmpp.ru” and “byte.catcher@0nl1ne.at”. His software is for sale at antidetect[dot]net and antidetect[dot]org.

Searching on that ICQ number turns up a post on a Russian forum from 2006, wherein a fifth-year computer science student posting under the name “pavelvladimirovich” says he is looking for a job and that he can be reached at the following contact points:

ICQ: 737084

Skype name: pavelvladimirovich1

email: gpvx@yandex.ru

According to a reverse WHOIS lookup ordered from Domaintools.com, that email address is the same one used to register the aforementioned antidetect[dot]org, as well as antifraud[dot]biz and hwidspoofer[dot]com (HWID is short for hardware identification, a common method that software makers use to ensure a given program license can only be used on one computer).

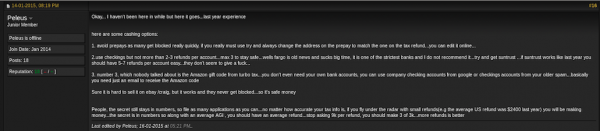

These were quite recent registrations (mid-2014), but that gpvx@yandex.ru email also was used to register domains in 2007, including allfreelance[dot]org and a domain called casinohackers[dot]com. Interestingly, one of the main uses that Byte Catcher advertises for his Antidetect software is to help beat fraud detection mechanisms used by online casinos. As we can see from this page at archive.org, a subsection of casinohackers.com was at one time dedicated to advertising Antidetect Patch — a version that comes with its own virtual machine.

That ICQ number is tied to a user named “collisionsoftware” at the Russian cybercrime forum antichat[dot]ru, in which the seller is advertising software that routes the user’s Internet connection through hacked PCs. He directs interested buyers to the web site cn[dot]viamk[dot]com, which is no longer online. But an archived version of that page at archive.org shows the same “collision” name and the words “freelance team.” The contact form on this site also lists the above-referenced ICQ number and email gpvx@yandex.ru, and even includes a résumé of the site’s owner.

Another domain connected to that antichat profile is cnsoft[dot]ru, the now defunct domain for Collision Software, which bills itself as a firm that can be hired to write software. The homepage lists the same ICQ number (737084).

The ICQ.com profile page for that number includes links to accounts on Russian fraud forums that are all named “Mysterious Killer.” In one of those accounts, on the fraud forum exploit[dot]in, Mysterious Killer lists the same Jabber and ICQ addresses, and offers a variety of services, including a tool to mass-check PayPal account credentials, as well as a full instructional course on click-fraud.

Both antifraud[dot]biz and allfreelance[dot]org were originally registered by an individual in Kaliningrad, Russia named Pavel V. Golub. Note that this name matches the initials in the email address gpvx@yandex.ru. KrebsOnSecurity has yet to receive a response to inquiries sent to that email and to the above-referenced Skype profile. Update, 1:05 p.m.: Pavel replied to my email, denying that he produced the video selling his software. “My software was cracked few years ago and then it as spreaded, selled by other people,” he wrote. Meanwhile, someone has started deleting photos and other items linked in this story.

Original story:

A little searching turns up this profile on Russian social networking giant Odnoklassniki.ru for one Pavel Golub, a 29-year-old male from Koenig, Russia. Written in Russian as “Кениг,” this is Russian slang for Kaliningrad and refers to the city’s previous German name.

One of Pavel’s five friends on Odnoklassniki is 27-year-old Vera Golub, also of Kaliningrad. A search of “Vera Golub, Kaliningrad” on vkontakte.com — Russia’s version of Facebook — reveals a vk.com group in Kaliningrad about artificial fingernails that has two contacts: Vera Ivanova (referred to as “master” in this group), and Pavel Vladimirovich (listed as “husband”). Continue reading