Microsoft is warning Internet Explorer users about active attacks that attempt to exploit a previously unknown security flaw in every supported version of IE. The vulnerability could be used to silently install malicious software without any help from users, save for perhaps merely browsing to a hacked or malicious site.

In an alert posted on Saturday, Microsoft said it is aware of “limited, targeted attacks” against the vulnerability (CVE-2014-1776) so far.

Microsoft’s security advisory credits security firm FireEye with discovering the attack. In its own advisory, FireEye says the exploit currently is targeting IE9 through IE11 (although the weakness also is present in all earlier versions of IE going back to IE6), and that it leverages a well-known Flash exploitation technique to bypass security protections on Windows.

Microsoft has not yet issued a stopgap “Fix-It” solution for this vulnerability. For now, it is urging IE users to download and install its Enhanced Mitigation Experience Toolkit (EMET), a free tool that can help beef up security on Windows. Microsoft notes that EMET 3.0 doesn’t mitigate this attack, and that affected users should instead rely on EMET 4.1. I’ve reviewed the basics of EMET here. The latest versions of EMET are available here.

Microsoft has not yet issued a stopgap “Fix-It” solution for this vulnerability. For now, it is urging IE users to download and install its Enhanced Mitigation Experience Toolkit (EMET), a free tool that can help beef up security on Windows. Microsoft notes that EMET 3.0 doesn’t mitigate this attack, and that affected users should instead rely on EMET 4.1. I’ve reviewed the basics of EMET here. The latest versions of EMET are available here.

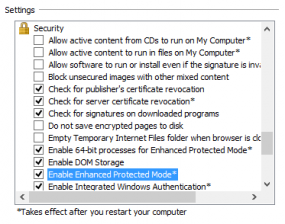

According to information shared by FireEye, the exploit also can be blocked by running Internet Explorer in “Enhanced Protected Mode” configuration and 64-bit process mode, which is available for IE10 and IE11 in the Internet Options settings as shown in the graphic above.

This is the first of many zero-day attacks and vulnerabilities that will never be fixed for Windows XP users. Microsoft last month shipped its final set of updates for XP. Unfortunately, many of the exploit mitigation techniques that EMET brings do not work in XP.