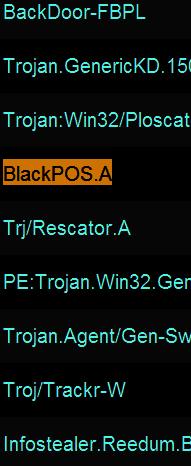

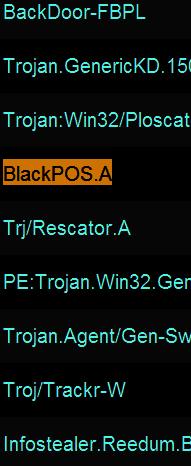

Ever since news broke that thieves stole more than 40 million debit and credit card accounts from Target using a strain of Point-Of-Sale malware known as BlackPOS, much speculation has swirled around unanswered questions, such as how this malware was introduced into the network, and what mechanisms were used to infect thousands of Target’s cash registers.

Recently, I spoke at length with Tom Arnold and Paul Guthrie, co-founders of PSC, a security firm that consults for businesses on payment security and compliance. In early 2013, these two experts worked directly on a retail data breach that involved a version of BlackPOS. They agreed to talk about their knowledge of this malware, and how the attackers worked to defeat the security of the retail client (not named in this story).

Recently, I spoke at length with Tom Arnold and Paul Guthrie, co-founders of PSC, a security firm that consults for businesses on payment security and compliance. In early 2013, these two experts worked directly on a retail data breach that involved a version of BlackPOS. They agreed to talk about their knowledge of this malware, and how the attackers worked to defeat the security of the retail client (not named in this story).

While some of this discussion may be geektacular at times (what I affectionately like to call “Geek Factor 5”), there’s something in here for everyone. Their observations about the methods and approaches used in this attack point to an adversary that is skilled, organized, patient and thorough.

So you first saw BlackPOS at a retailer in early January 2013?

Tom: Yes, it did seem like a game changer at that point because of the way it hooked into the POS system. By that I mean the fact that it hooks into the POS process, and it’s not just a general memory scraper like some people have stated.

Help me understand the distinction between a memory scraper and malware that runs completely in memory?

Tom: Well, it’s very specific. It’s what’s called an inter-process communications hook. If you look at a memory scraper — so if you were to dump the memory on your laptop right now — you would get this big old blob of information and you would have to filter through it to find what you’re looking for. But this [malware] is very specific: It’s very much designed for the POS system it’s running on, because it knows exactly where to hook and where the memory location is going to be when the data it’s looking for is flowing through it. But if you look at what it captures, it captures only the track data [information stored on the magnetic strip on the backs of cards]. So, it’s actually very, very sophisticated and that’s why I think this isn’t just a teenage hacker who put this together in his basement. I think this is a more sophisticated development effort. [HP last week published some interesting, uber-geeky details about the memory behavior of the version of BlackPOS found at Target].

Paul: It certainly hooks into a specific process, but we did not figure out if it was just good at scraping the memory of that process, or whether it actually altered the process to hook into the code somehow. That part of the code was obfuscated and not reviewed during the engagement.

What did you think of the iSight paper?

Tom: The iSight paper was good, and what it described was very similar to what we saw in the first variants of BlackPOS. But it didn’t talk about how it appeared on the network or where it came from or how a retailer might defend themselves against it.

In your prior experience with BlackPOS, has it been used against the same POS that Target uses? A source who seemed to have a clue told me that their setup was somewhat homegrown.

Tom: That I don’t know. I haven’t really looked at what Target uses. With a homegrown system, the problem is if you’re going to build a process hook, you have to have a test environment, you have to know what you’re looking at and what memory addresses to go after, and that’s not exactly something that gets published.

Paul: Target has a homegrown POS.

So you think it’s likely they were using some off-the-shelf equipment and software? Wouldn’t it be enough for the attackers in this case to have obtained a physical point of sale device that was once used at Target?

Tom: If they have one, sure, that would be different. I don’t know if they’re using a commercial product. A lot of the big retailers use commercial products and will customize those with their back end system. But at the front end and what happens at front of the house…a lot of those are just retail off-the-shelf applications. A lot of those retailers, when you have a hard disk that breaks on one of the [checkout] lanes, they’ve got an outsourced service provider of that POS that comes out there with a new hard disk and fixes it.

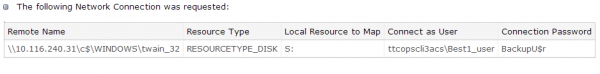

How do the bad guys break in, and how do they actually get the malware pushed out to the point-of-sale?

Tom: A lot of the POS systems use whitelisting software of some kind, such as Bit9 or SolidCore. Those two companies are the two you see most out there in the industry.

Paul: It could also come in through the point-of-sale application update process.

By whitelisting, you mean sort of the opposite approach of antivirus, right? As in, if the file or program isn’t approved by the whitelisting software, it simply won’t run on the system?

Tom: The software update processes at a point-of-sale that is running one of those [whitelisting applications] has to come through one of the software update channels and has to be reviewed for the update and approved. And when it’s approved, the whitelisting software says okay this patch is approved to come online.

It’s probably a good idea at this point to make sure we’re defining the terminology in a uniform way. When you think of point-of-sale device, are you talking about the cash register, or the card swipe terminal, or…

Tom: I’m using point-of-sale to mean the payment application that is running on the cash register. The vast majority of those devices, when you check out at the grocery store or large retailer, those are just PCs, and yes they’re mostly running Windows XP or WEPOS as their operating system. But above that, you have what I call the point-of-sale, or the point-of-sale application, and that’s the stuff that the cashier is interfacing with at the time you’re checking out. It’s a software application, running as multiple pieces of software inside the register itself. And whitelisting is put on to protect the register from any sort of unsolicited modification. A lot of the attacks before this [whitelisting became more broadly used] involved where you corrupt a sales clerk to put a USB stick in the cash register and infect the PC with some malware. But by using a whitelisting software, the USB stick will not work and the operations personnel back in the head office will get notified that something isn’t right with that register.

If they get past a whitelisting system, doesn’t that suggest that someone on the inside would have to be involved?

Tom: No, not really. You have to also consider the distribution server that distributes the point-of-sale software.

Paul: Right… three possible ways… it could come through a legitimate update channel, or the retailer was lax in their update procedures, or the attackers hacked the console of the whitelisting software and just whitelisted it themselves.

Continue reading →

More than half of the updates issued by Microsoft today earned a “critical” rating — Microsoft’s most dire. That rating is assigned to vulnerabilities that can be exploited by malware or malcontents to take complete, remote control over vulnerable systems — with no help from users.

More than half of the updates issued by Microsoft today earned a “critical” rating — Microsoft’s most dire. That rating is assigned to vulnerabilities that can be exploited by malware or malcontents to take complete, remote control over vulnerable systems — with no help from users.