Media attention to crimes involving ATM skimmers may make consumers more likely to identify compromised cash machines, which involve cleverly disguised theft devices that sometimes appear off-color or out-of-place. Yet, many of today’s skimmer scams can swipe your card details and personal identification number while leaving the ATM itself completely untouched, making them far more difficult to spot.

The most common of these off-ATM skimmers can be found near cash machines that are located in the antechamber of a bank or building lobby, where access is controlled by a key card lock that is activated when the customer swipes his or her ATM card. In these scams, the thieves remove the card swipe device attached to the outside door, add a skimmer, and then reattach the device to the door. The attackers then place a hidden camera just above or beside the ATM, so that the camera is angled to record unsuspecting customers entering their PINs.

The crooks usually return later in the evening to remove the theft devices. Armed with skimmed card data and victim PINs, skimmer thieves are able to encode the information onto counterfeit cards and withdraw money from compromised accounts at ATMs across the country.

On July 24, 2009, California police officers responded to a report that a customer had uncovered a camera hidden behind a mirror that was stuck to the wall above an ATM at a bank in Sherman Oaks, Calif. There were two ATMs in the lobby where the camera was found, and officers discovered that the thieves had placed an “Out of Order” sign on the ATM that did not have the camera pointed at its PIN pad. The sign was a simple ruse designed to trick all customers into using the cash machine that was compromised.

Bank security cameras at the scene of the crime show the fake mirror installed over the ATM on the right.

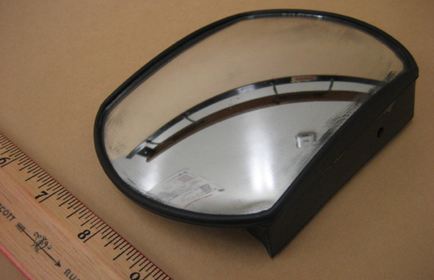

Here’s a front view of the hidden camera, which probably would appear to most ATM users as nothing more than a parabolic mirror designed to give customers a view of anyone standing behind them.

Behind the glass, however, was a battery-operated hidden camera. A tiny hole was cut out of the bottom of the mirror housing to enable the camera to record PIN entries.

Below are several images showing the key card door lock that was compromised in this attack. The top left image shows the device as it would appear attached to the door securing access to the ATM lobby. The other two pictures show the skimmer device with the electronic components added by the thieves.