Image: Shutterstock.

A cybersecurity firm says it has intercepted a large, unique stolen data set containing the names, addresses, email addresses, phone numbers, Social Security Numbers and dates of birth on nearly 23 million Americans. The firm’s analysis of the data suggests it corresponds to current and former customers of AT&T. The telecommunications giant stopped short of saying the data wasn’t theirs, but it maintains the records do not appear to have come from its systems and may be tied to a previous data incident at another company.

Milwaukee-based cybersecurity consultancy Hold Security said it intercepted a 1.6 gigabyte compressed file on a popular dark web file-sharing site. The largest item in the archive is a 3.6 gigabyte file called “dbfull,” and it contains 28.5 million records, including 22.8 million unique email addresses and 23 million unique SSNs. There are no passwords in the database.

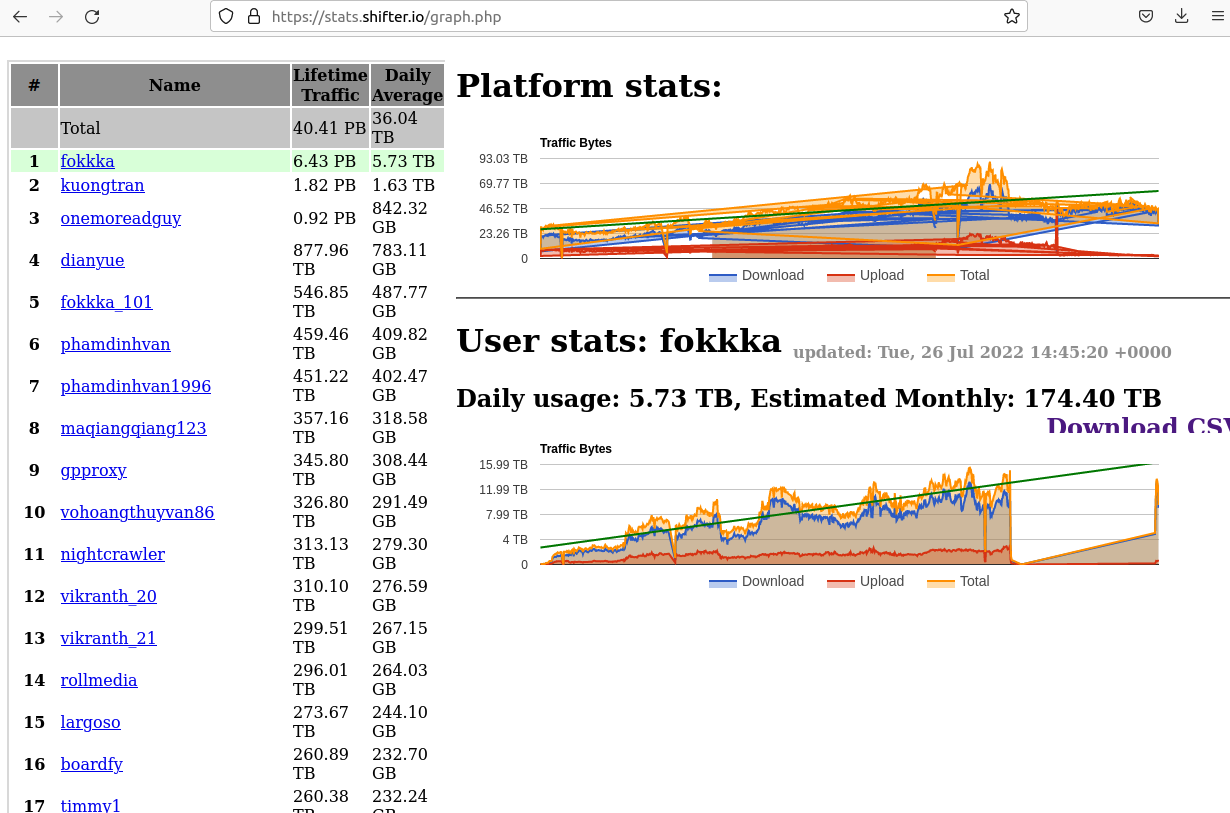

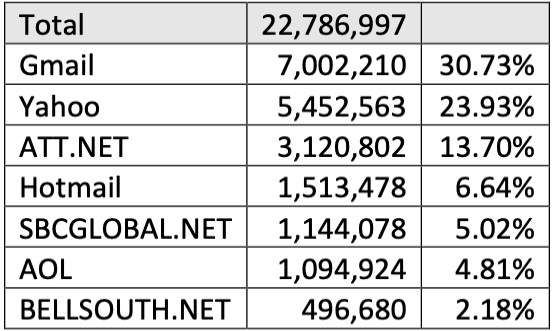

Hold Security founder Alex Holden said a number of patterns in the data suggest it relates to AT&T customers. For starters, email addresses ending in “att.net” accounted for 13.7 percent of all addresses in the database, with addresses from SBCGLobal.net and Bellsouth.net — both AT&T companies — making up another seven percent. In contrast, Gmail users made up more than 30 percent of the data set, with Yahoo addresses accounting for 24 percent. More than 10,000 entries in the database list “none@att.com” in the email field.

Hold Security found these email domains account for 87% of all domains in the data set. Nearly 21% belonged to AT&T customers.

Holden’s team also examined the number of email records that included an alias in the username portion of the email, and found 293 email addresses with plus addressing. Of those, 232 included an alias that indicated the customer had signed up at some AT&T property; 190 of the aliased email addresses were “+att@”; 42 were “+uverse@,” an oddly specific reference to an AT&T entity that included broadband Internet. In September 2016, AT&T rebranded U-verse as AT&T Internet.

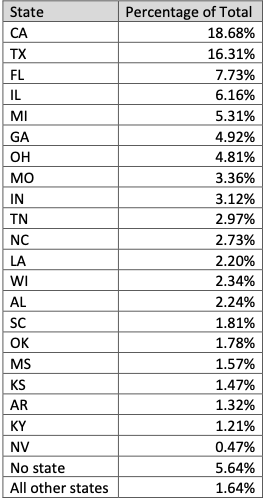

According to its website, AT&T Internet is offered in 21 states, including Alabama, Arkansas, California, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Michigan, Missouri, Nevada, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Tennessee, Texas and Wisconsin. Nearly all of the records in the database that contain a state designation corresponded to those 21 states; all other states made up just 1.64 percent of the records, Hold Security found.

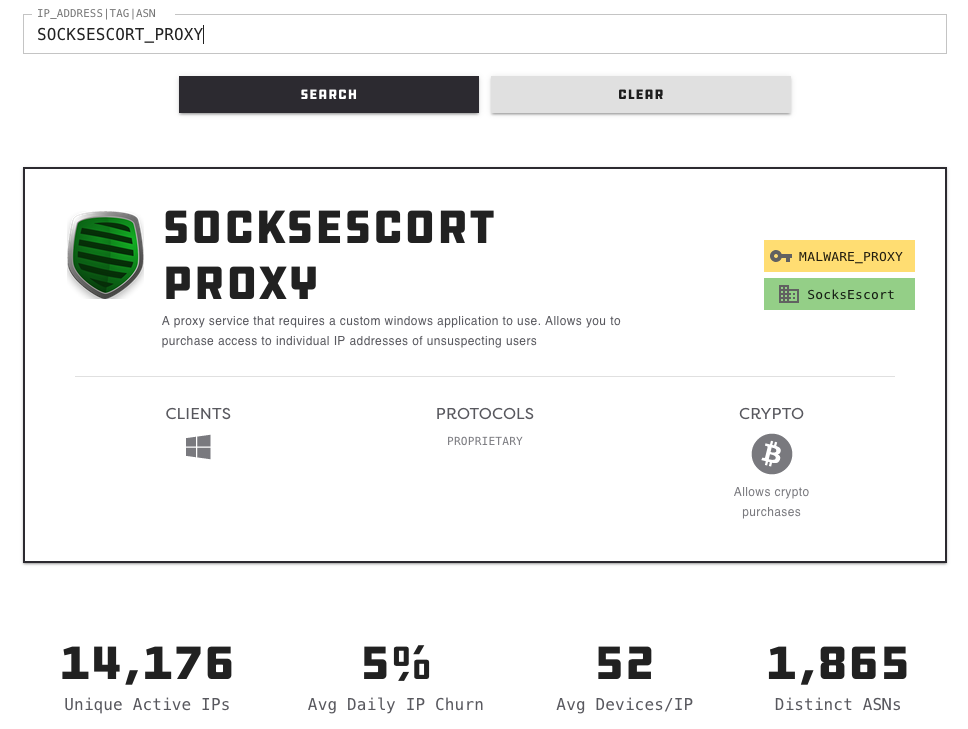

Image: Hold Security.

The vast majority of records in this database belong to consumers, but almost 13,000 of the entries are for corporate entities. Holden said 387 of those corporate names started with “ATT,” with various entries like “ATT PVT XLOW” appearing 81 times. And most of the addresses for these entities are AT&T corporate offices.

How old is this data? One clue may be in the dates of birth exposed in this database. There are very few records in this file with dates of birth after 2000.

“Based on these statistics, we see that the last significant number of subscribers born in March of 2000,” Holden told KrebsOnSecurity, noting that AT&T requires new account holders to be 18 years of age or older. “Therefore, it makes sense that the dataset was likely created close to March of 2018.”

There was also this anomaly: Holden said one of his analysts is an AT&T customer with a 13-letter last name, and that her AT&T bill has always had the same unique misspelling of her surname (they added yet another letter). He said the analyst’s name is identically misspelled in this database.

KrebsOnSecurity shared the large data set with AT&T, as well as Hold Security’s analysis of it. AT&T ultimately declined to say whether all of the people in the database are or were at some point AT&T customers. The company said the data appears to be several years old, and that “it’s not immediately possible to determine the percentage that may be customers.”

“This information does not appear to have come from our systems,” AT&T said in a written statement. “It may be tied to a previous data incident at another company. It is unfortunate that data can continue to surface over several years on the dark web. However, customers often receive notices after such incidents, and advice for ID theft is consistent and can be found online.”

The company declined to elaborate on what they meant by “a previous data incident at another company.”

But it seems likely that this database is related to one that went up for sale on a hacker forum on August 19, 2021. That auction ran with the title “AT&T Database +70M (SSN/DOB),” and was offered by ShinyHunters, a well-known threat actor with a long history of compromising websites and developer repositories to steal credentials or API keys. Continue reading