The FBI confirmed this week that a relatively new ransomware group known as DarkSide is responsible for an attack that caused Colonial Pipeline to shut down 5,550 miles of pipe, stranding countless barrels of gasoline, diesel and jet fuel on the Gulf Coast. Here’s a closer look at the DarkSide cybercrime gang, as seen through their negotiations with a recent U.S. victim that earns $15 billion in annual revenue.

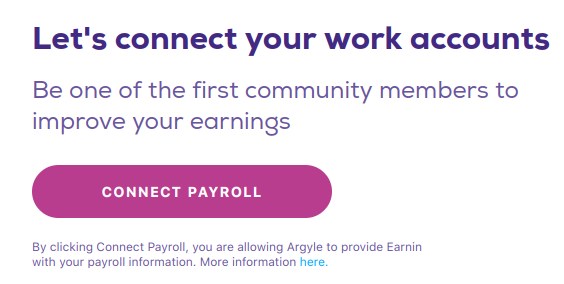

Colonial Pipeline has shut down 5,500 miles of fuel pipe in response to a ransomware incident. Image: colpipe.com

New York City-based cyber intelligence firm Flashpoint said its analysts assess with a moderate-strong degree of confidence that the attack was not intended to damage national infrastructure and was simply associated with a target which had the finances to support a large payment.

“This would be consistent with DarkSide’s earlier activities, which included several ‘big game hunting’ attacks, whereby attackers target an organization that likely possesses the financial means to pay the ransom demanded by the attackers,” Flashpoint observed.

In response to public attention to the Colonial Pipeline attack, the DarkSide group sought to play down fears about widespread infrastructure attacks going forward.

“We are apolitical, we do not participate in geopolitics, do not need to tie us with a defined government and look for other our motives [sic],” reads an update to the DarkSide Leaks blog. “Our goal is to make money, and not creating problems for society. From today we introduce moderation and check each company that our partners want to encrypt to avoid social consequences in the future.”

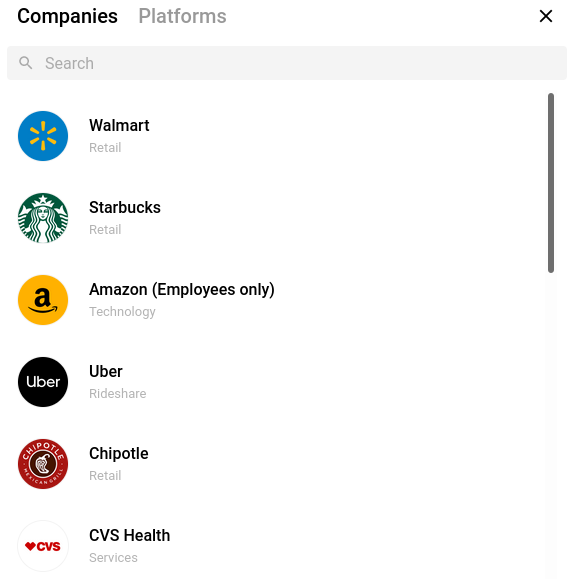

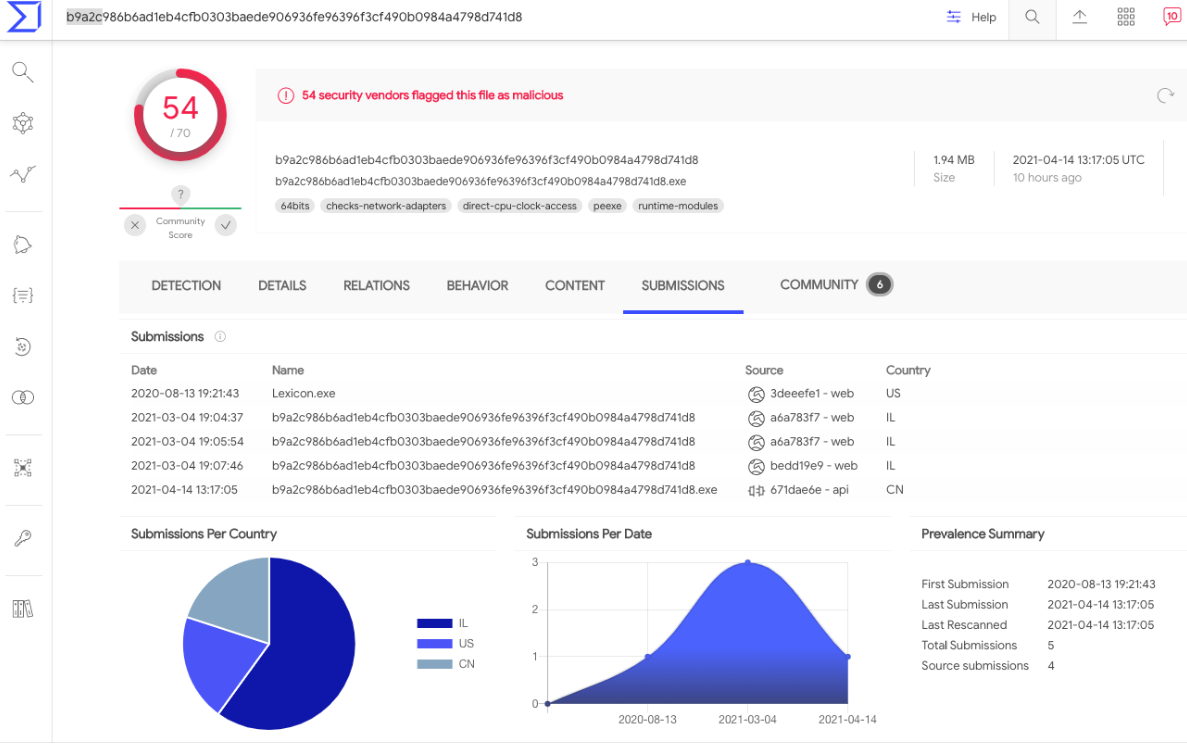

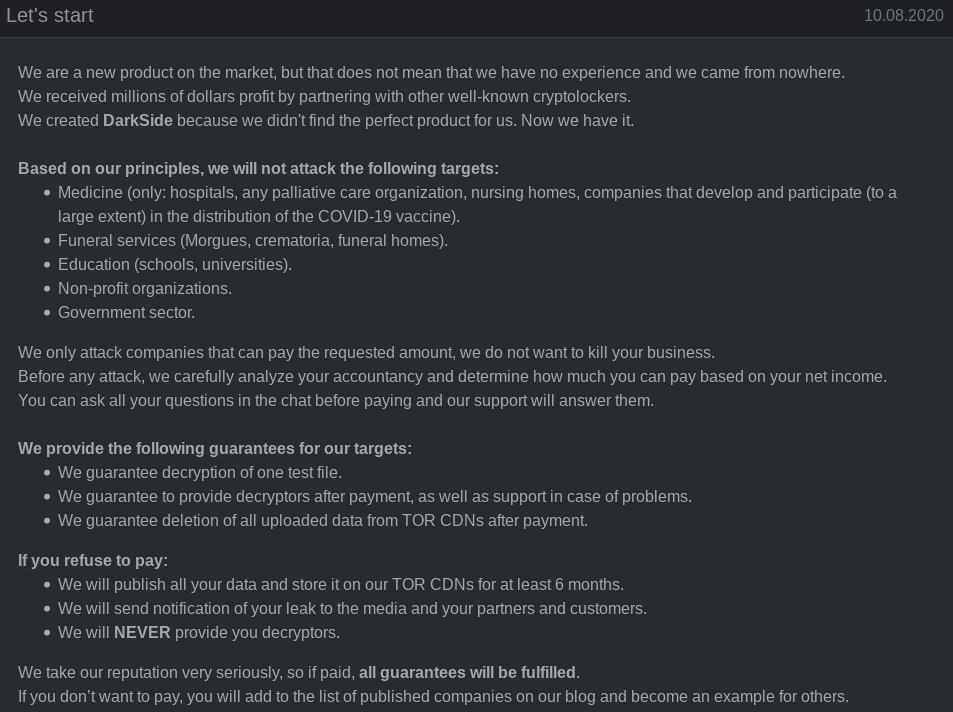

First surfacing on Russian language hacking forums in August 2020, DarkSide is a ransomware-as-a-service platform that vetted cybercriminals can use to infect companies with ransomware and carry out negotiations and payments with victims. DarkSide says it targets only big companies, and forbids affiliates from dropping ransomware on organizations in several industries, including healthcare, funeral services, education, public sector and non-profits.

Like other ransomware platforms, DarkSide adheres to the current badguy best practice of double extortion, which involves demanding separate sums for both a digital key needed to unlock any files and servers, and a separate ransom in exchange for a promise to destroy any data stolen from the victim.

At its launch, DarkSide sought to woo affiliates from competing ransomware programs by advertising a victim data leak site that gets “stable visits and media coverage,” as well as the ability to publish victim data by stages. Under the “Why choose us?” heading of the ransomware program thread, the admin answers:

An advertisement for the DarkSide ransomware group.

“High trust level of our targets. They pay us and know that they’re going to receive decryption tools. They also know that we download data. A lot of data. That’s why the percent of our victims who pay the ransom is so high and it takes so little time to negotiate.”

In late March, DarkSide introduced a “call service” innovation that was integrated into the affiliate’s management panel, which enabled the affiliates to arrange calls pressuring victims into paying ransoms directly from the management panel.

In mid-April the ransomware program announced new capability for affiliates to launch distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks against targets whenever added pressure is needed during ransom negotiations.

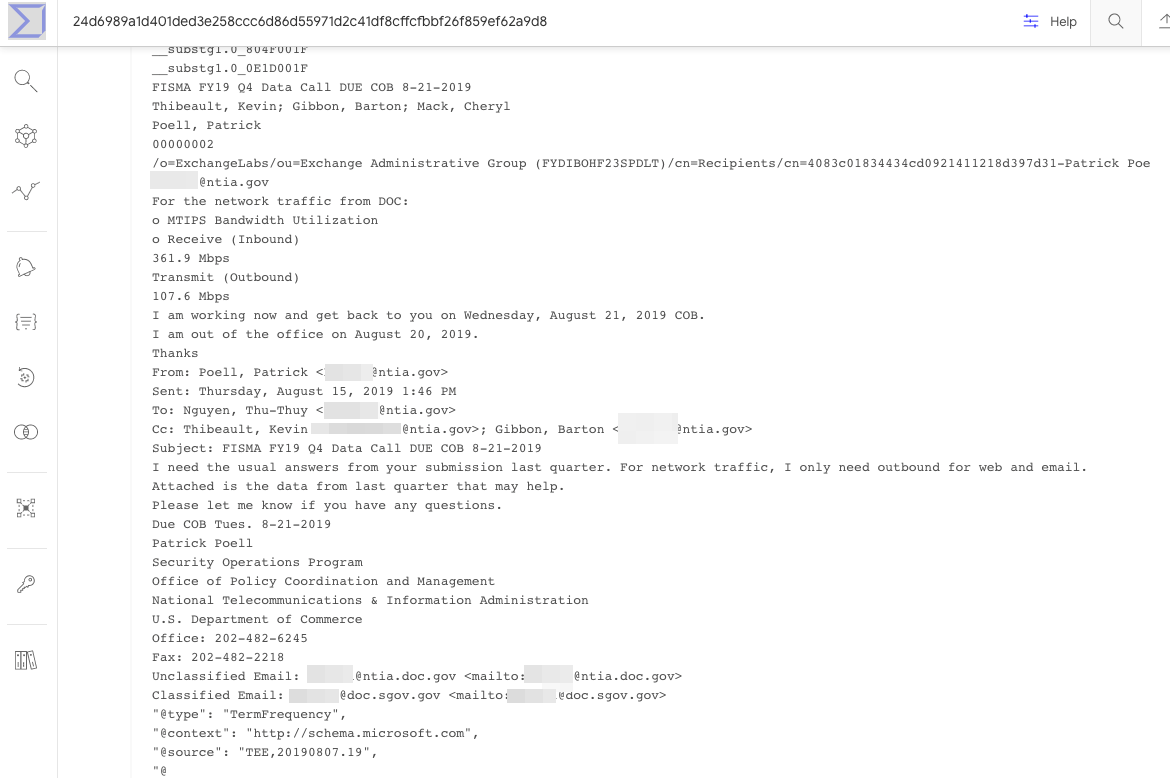

DarkSide also has advertised a willingness to sell information about upcoming victims before their stolen information is published on the DarkSide victim shaming blog, so that enterprising investment scammers can short the company’s stock in advance of the news.

“Now our team and partners encrypt many companies that are trading on NASDAQ and other stock exchanges,” DarkSide explains. “If the company refuses to pay, we are ready to provide information before the publication, so that it would be possible to earn in the reduction price of shares. Write to us in ‘Contact Us’ and we will provide you with detailed information.”

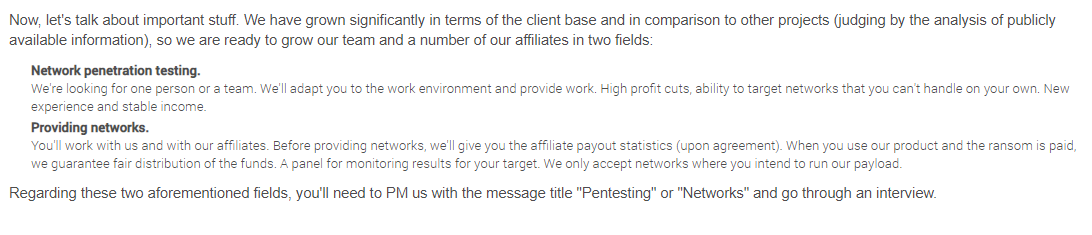

DarkSide also started recruiting new affiliates again last month — mainly seeking network penetration testers who can help turn a single compromised computer into a full-on data breach and ransomware incident.

“We have grown significantly in terms of the client base and in comparison to other projects (judging by the analysis of publicly available information), so we are ready to grow our team and a number of our affiliates in two fields,” DarkSide explained. The advertisement continued:

“Network penetration testing. We’re looking for one person or a team. We’ll adapt you to the work environment and provide work. High profit cuts, ability to target networks that you can’t handle on your own. New experience and stable income. When you use our product and the ransom is paid, we guarantee fair distribution of the funds. A panel for monitoring results for your target. We only accept networks where you intend to run our payload.”

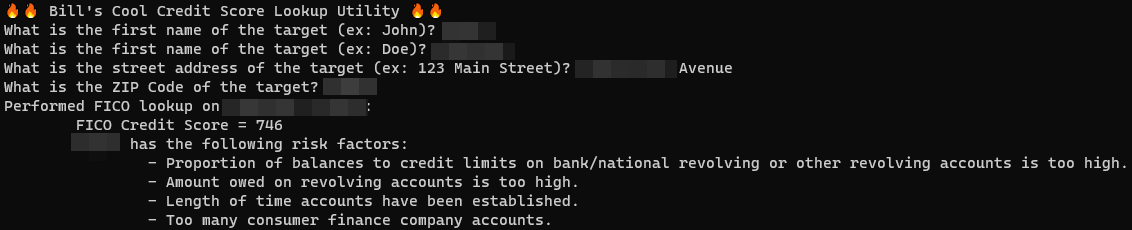

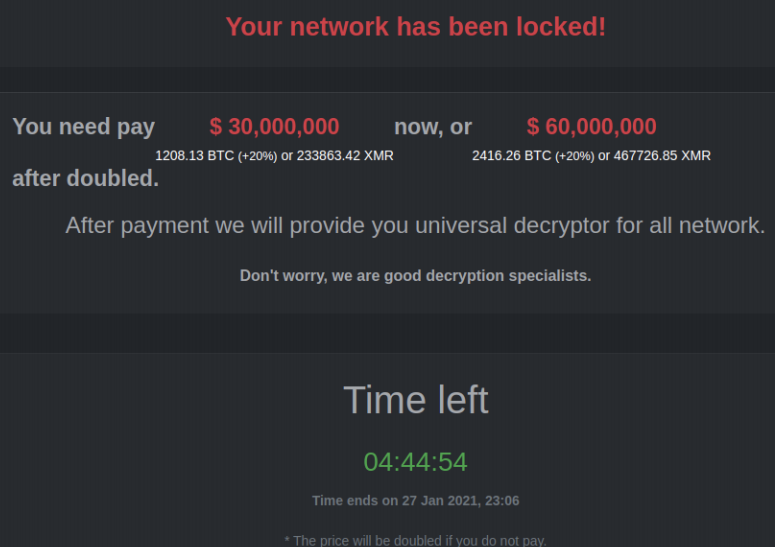

DarkSide has shown itself to be fairly ruthless with victim companies that have deep pockets, but they can be reasoned with. Cybersecurity intelligence firm Intel 471 observed a negotiation between the DarkSide crew and a $15 billion U.S. victim company that was hit with a $30 million ransom demand in January 2021, and in this incident the victim’s efforts at negotiating a lower payment ultimately reduce the ransom demand by almost two-thirds.

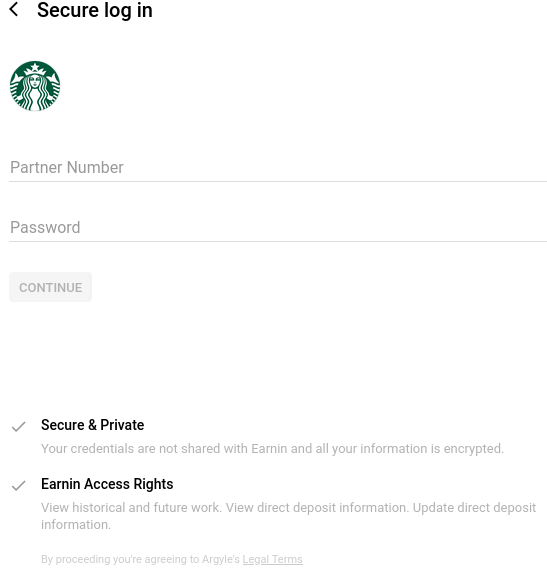

The DarkSide ransomware note.

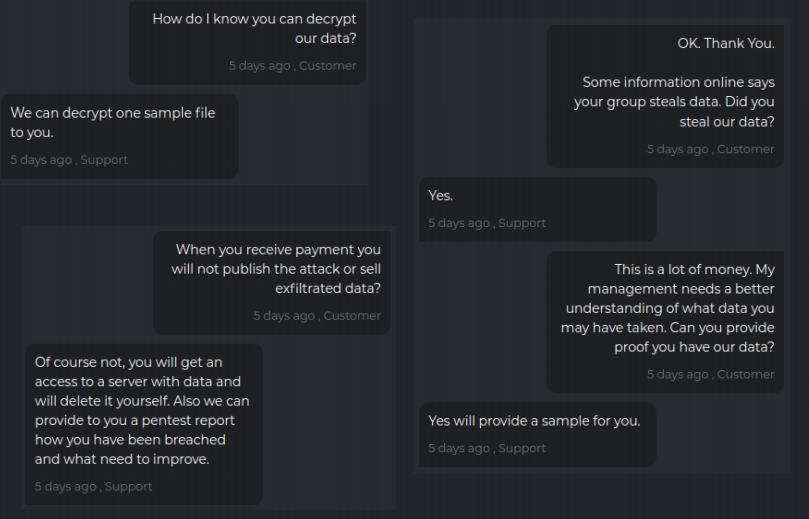

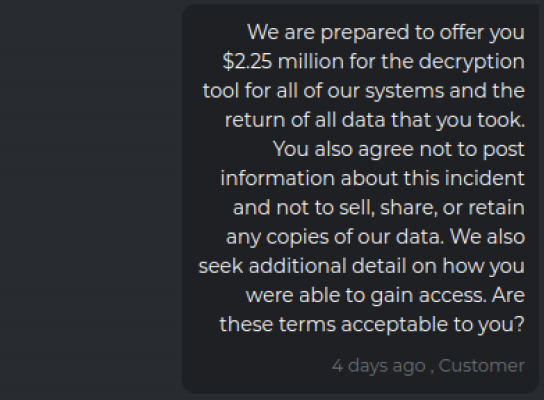

The first exchange between DarkSide and the victim involved the usual back-and-forth establishing of trust, wherein the victim asks for assurances that stolen data will be deleted after payment.

When the victim counter-offered to pay just $2.25 million, DarkSide responded with a lengthy, derisive reply, ultimately agreeing to lower the ransom demand to $28.7 million.

“The timer it [sic] ticking and in in next 8 hours your price tag will go up to $60 million,” the crooks replied. “So, you this are your options first take our generous offer and pay to us $28,750 million US or invest some monies in quantum computing to expedite a decryption process.” Continue reading