Cloud hosting provider Dataresolution.net is struggling to bring its systems back online after suffering a ransomware infestation on Christmas Eve, KrebsOnSecurity has learned. The company says its systems were hit by the Ryuk ransomware, the same malware strain that crippled printing and delivery operations for multiple major U.S. newspapers over the weekend.

San Juan Capistrano, Calif. based Data Resolution LLC serves some 30,000 businesses worldwide, offering software hosting, business continuity systems, cloud computing and data center services.

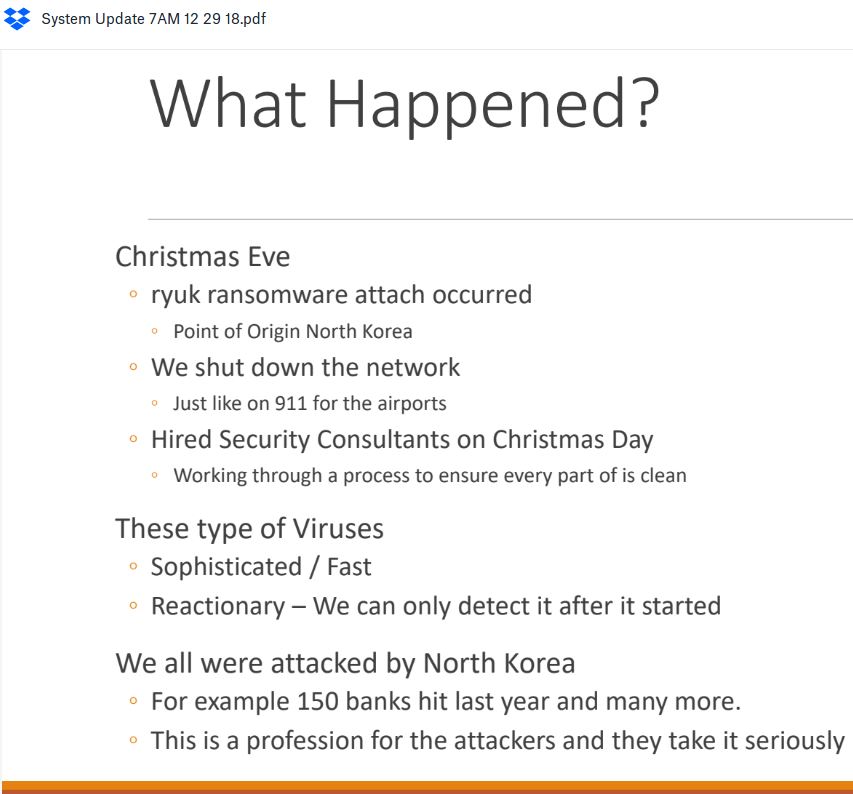

The company has not yet responded to requests for comment. But according to a status update shared by Data Resolution with affected customers on Dec. 29, 2018, the attackers broke in through a compromised login account on Christmas Eve and quickly began infecting servers with the Ryuk ransomware strain.

Part of an update on the outage shared with Data Resolution customers via Dropbox on Dec. 29, 2018.

The intrusion gave the attackers control of Data Resolution’s data center domain, briefly locking the company out of its own systems. The update sent to customers states that Data Resolution shut down its network to halt the spread of the infection and to work through the process of cleaning and restoring infected systems.

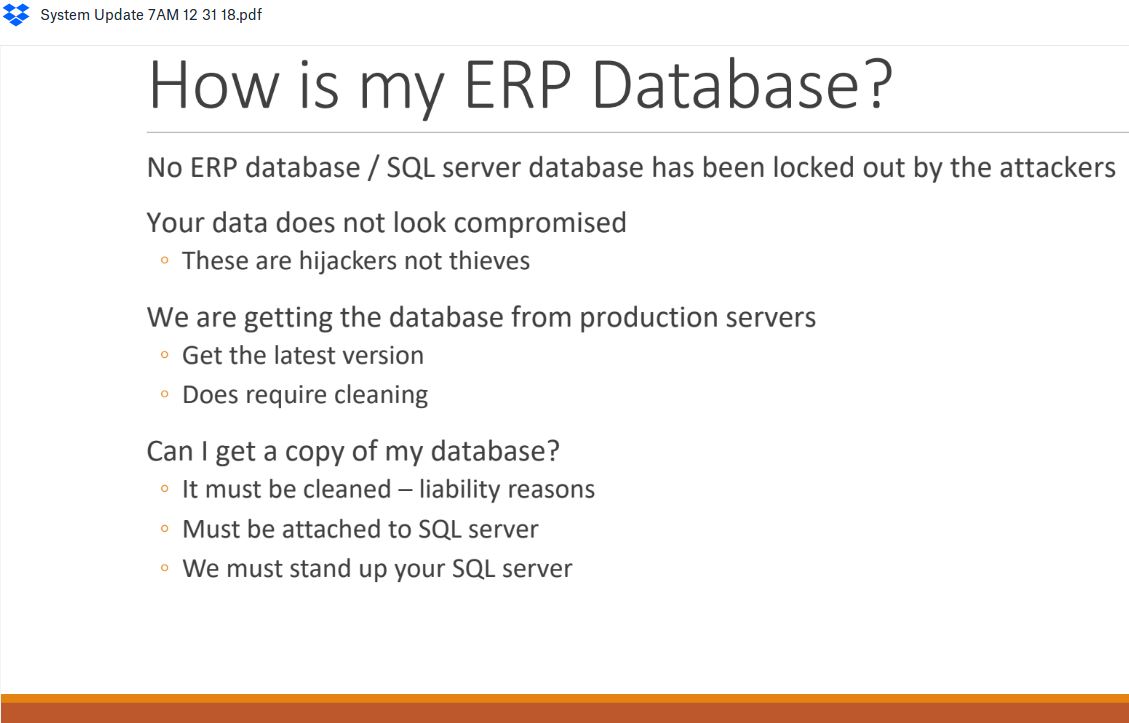

Data Resolution is assuring customers that there is no indication any data was stolen, and that the purpose of the attack was to extract payment from the company in exchange for a digital key that could be used to quickly unlock access to servers seized by the ransomware.

A snippet of an update that Data Resolution shared with affected customers on Dec. 31, 2018.

The Ryuk ransomware strain was first detailed in an August 2018 report by security firm CheckPoint, which says the malware may be tied to a sophisticated North Korean hacking team known as the Lazarus Group.

Ryuk reportedly was the same malware that infected the Los Angeles Times‘ Olympic printing plant over the weekend, an attack that led to the disruption of newspaper printing and delivery services for a number of publications that rely on the plant — including the Los Angeles Times and the San Diego Union Tribune.

A status update shared by Data Resolution with affected customers earlier today indicates the cloud hosting provider is still working to restore email access and multiple databases for clients. The update also said Data Resolution is in the process of restoring service for companies relying on it to host installations of Dynamics GP, a popular software package that many organizations use for accounting and payroll services. Continue reading

This past year featured some

This past year featured some

The software giant

The software giant

At least nine of the bugs in the Microsoft patches address flaws the company deems “critical,” meaning they can be exploited by malware or ne’er-do-wells to install malicious software with little or no help from users, save for perhaps browsing to a hacked or booby-trapped site.

At least nine of the bugs in the Microsoft patches address flaws the company deems “critical,” meaning they can be exploited by malware or ne’er-do-wells to install malicious software with little or no help from users, save for perhaps browsing to a hacked or booby-trapped site.