KrebsOnSecurity recently had a chance to interview members of the REACT Task Force, a team of law enforcement officers and prosecutors based in Santa Clara, Calif. that has been tracking down individuals engaged in unauthorized “SIM swaps” — a complex form of mobile phone fraud that is often used to steal large amounts of cryptocurrencies and other items of value from victims. Snippets from that fascinating conversation are recounted below, and punctuated by accounts from a recent victim who lost more than $100,000 after his mobile phone number was hijacked.

In late September 2018, the REACT Task Force spearheaded an investigation that led to the arrest of two Missouri men — both in their early 20s — who are accused of conducting SIM swaps to steal $14 million from a cryptocurrency company based in San Jose, Calif. Two months earlier, the task force was instrumental in apprehending 20-year-old Joel Ortiz, a Boston man suspected of stealing millions of dollars in cryptocoins with the help of SIM swaps.

Samy Tarazi is a sergeant with the Santa Clara County Sheriff’s office and a REACT supervisor. The force was originally created to tackle a range of cybercrimes, but Tarazi says SIM swappers are a primary target now for two reasons. First, many of the individuals targeted by SIM swappers live in or run businesses based in northern California.

More importantly, he says, the frequency of SIM swapping attacks is…well, off the hook right now.

“It’s probably REACT’s highest priority at the moment, given that SIM swapping is actively happening to someone probably even as we speak right now,” Tarazi said. “It’s also because there are a lot of victims in our immediate jurisdiction.”

As common as SIM swapping has become, Tarazi said he and other members of REACT suspect that there are only a few dozen individuals responsible for perpetrating most of these heists.

“For the amounts being stolen and the number of people being successful at taking it, the numbers are probably historic,” Tarazi said. “We’re talking about kids aged mainly between 19 and 22 being able to steal millions of dollars in cryptocurrencies. I mean, if someone gets robbed of $100,000 that’s a huge case, but we’re now dealing with someone who buys a 99 cent SIM card off eBay, plugs it into a cheap burner phone, makes a call and steals millions of dollars. That’s pretty remarkable.”

Indeed, the theft of $100,000 worth of cryptocurrency in July 2018 was the impetus for my interview with REACT. I reached out to the task force after hearing about their role in assisting SIM swapping victim Christian Ferri, who is president and CEO of San Francisco-based cryptocurrency firm BlockStar.

In early July 2018, Ferri was traveling in Europe when he discovered his T-Mobile phone no longer had service. He’d later learn that thieves had abused access to T-Mobile’s customer database to deactivate the SIM card in his phone and to activate a new one that they had in their own mobile device.

Soon after, the attackers were able to use their control over his mobile number to reset his Gmail account password. From there, the perpetrators accessed a Google Drive document that Ferri had used to record credentials to other sites, including a cryptocurrency exchange. Although that level of access could have let the crooks steal a great deal more from Ferri, they were simply after his cryptocoins, and in short order he was relieved of approximately $100,000 worth of coinage.

We’ll hear more about Ferri’s case in a moment. But first I should clarify that the REACT task force members did not discuss with me the details of Mr. Ferri’s case — even though according to Ferri a key member of the task force we’ll meet later has been actively investigating on his behalf. The remainder of this interview with REACT pivots off of Ferri’s incident mainly because the details surrounding his case help clarify some of the most confusing and murky aspects of how these crimes are perpetrated — and, more importantly, what we can do about them.

WHO’S THE TARGET?

SIM swapping attacks primarily target individuals who are visibly active in the cryptocurrency space. This includes people who run or work at cryptocurrency-focused companies; those who participate as speakers at public conferences centered around Blockchain and cryptocurrency technologies; and those who like to talk openly on social media about their crypto investments.

REACT Lieutenant John Rose said in addition to or in lieu of stealing cryptocurrency, some SIM swappers will relieve victims of highly prized social media account names (also known as “OG accounts“) — usually short usernames that can convey an aura of prestige or the illusion of an early adopter on a given social network. OG accounts typically can be resold for thousands of dollars.

Rose said even though a successful SIM swap often gives the perpetrator access to traditional bank accounts, the attackers seem to be mainly interested in stealing cryptocurrencies.

“Many SIM swap victims are understandably very scared at how much of their personal information has been exposed when these attacks occur,” Rose said. “But [the attackers] are predominantly interested in targeting cryptocurrencies for the ease with which these funds can be laundered through online exchanges, and because the transactions can’t be reversed.”

FAKE IDs AND PHONY NOTES

The “how” of these SIM swaps is often the most interesting because it’s the one aspect of this crime that’s probably the least well-understood. Ferri said when he initially contacted T-Mobile about his incident, the company told him that the perpetrator had entered a T-Mobile store and presented a fake ID in Ferri’s name.

But Ferri said once the REACT Task Force got involved in his case, it became clear that video surveillance footage from the date and time of his SIM swap showed no such evidence of anyone entering the store to present a fake ID. Rather, he said, this explanation of events was a misunderstanding at best, and more likely a cover-up at some level.

Caleb Tuttle, a detective with the Santa Clara County District Attorney’s office, said he has yet to encounter a single SIM swapping incident in which the perpetrator actually presented ID in person at a mobile phone store. That’s just too risky for the attackers, he said.

“I’ve talked to hundreds of victims, and I haven’t seen any cases where the suspect is going into a store to do this,” Tuttle said.

Tuttle said SIM swapping happens in one of three ways. The first is when the attacker bribes or blackmails a mobile store employee into assisting in the crime. The second involves current and/or former mobile store employees who knowingly abuse their access to customer data and the mobile company’s network. Finally, crooked store employees may trick unwitting associates at other stores into swapping a target’s existing SIM card with a new one.

“Most of these SIM swaps are being done over the phone, and the notes we’re seeing about the change in the [victim’s] account usually are left either by [a complicit] employee trying to cover their tracks, or because the employee who typed in that note actually believed what they were typing.” In the latter case, the employee who left a note in the customer’s account saying ID had been presented in-store was tricked by a complicit co-worker at another store who falsely claimed that a customer there had already presented ID.

DARK WEB SOFTWARE?

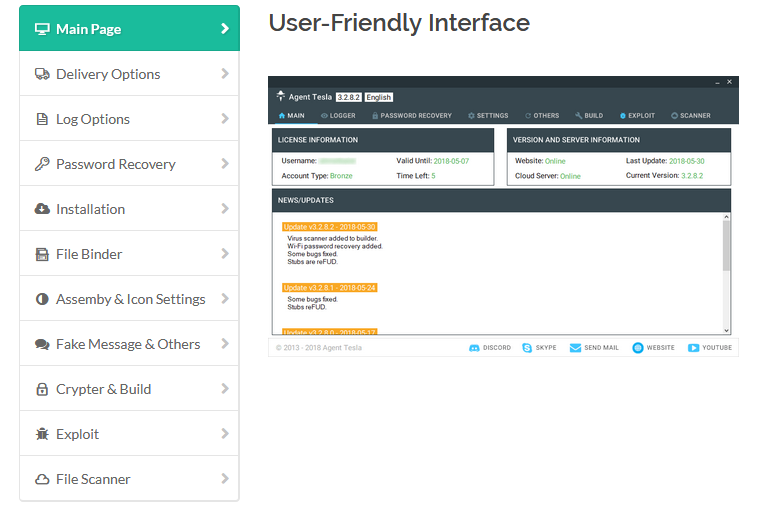

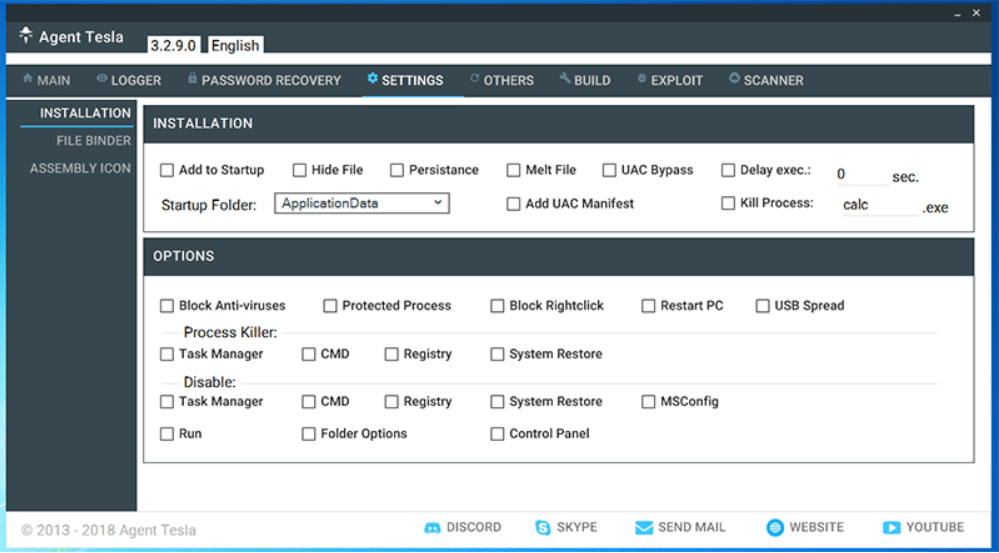

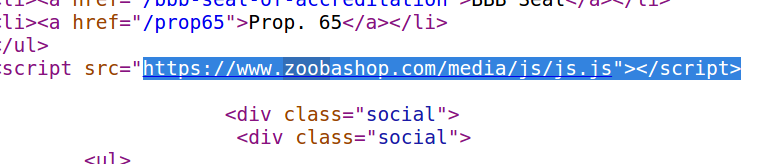

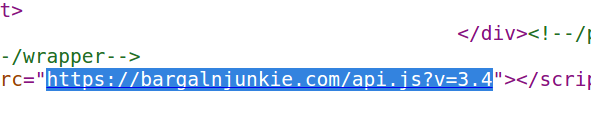

Ferri said the detectives investigating his SIM swap attack let on that the crooks responsible had at some point in the attack used “specialized software to get into T-Mobile’s customer database.”

“The investigator said there were employees of the company who had built a special software tool that they could use to connect to T-Mobile’s customer database, and that they could use this software from their home or couch to log in and see all the customer information there,” Ferri recalled. “The investigator didn’t explain exactly how it worked, but it was basically a backdoor entrance that they were reselling on the Dark Web, and it bypassed whatever security there was and let them go straight into the customer database.”

Asked directly about this mysterious product supposedly being offered on the Dark Web, the REACT task force members put our phone interview on hold for several minutes while they privately huddled to discuss the question. When they finally took me off mute, a member of the task force instead answered a different question that I’d asked much earlier in the interview.

When pressed about the software again, there was a long, uncomfortable silence. Then Detective Tuttle spoke up.

“We’re not going to talk about that,” he said curtly. “Deal with it.”

T-Mobile likewise declined to comment on the allegation that thieves had somehow built software which gave them direct access to T-Mobile customer data. However, in at least three separate instances over the past six months, T-Mobile has been forced to acknowledge incidents of unauthorized access to customer records.

In August 2018, T-Mobile published a notice saying its security team discovered and shut down unauthorized access to certain information, including customer name, billing zip code, phone number, email address, account number, account type (prepaid or postpaid) and/or date of birth. A T-Mobile spokesperson said at the time that this incident impacted roughly two percent of its subscriber base, or approximately 2.5 million customers.

In May 2018, T-Mobile fixed a bug in its Web site that let anyone view the personal account details of any customer. The bug could be exploited simply by adding the phone number of a target to the end of a Web address used by one of the company’s internal tools that was nevertheless accessible via the open Internet. The data provided by that tool reportedly also included references to account PINs used by customers as a security question when contacting T-Mobile customer support.

In April 2018, T-Mobile fixed a related bug in its public Web site that allowed anyone to pull data tied to customer accounts, including the user’s account number and the target phone’s IMSI — a unique number that ties subscribers to their specific mobile device. Continue reading →

According to the most recent statistics from the FBI‘s

According to the most recent statistics from the FBI‘s