A bill moving through the U.S. Senate that would grant the government greater power to shutter Web sites that host copyright-infringing content is under fire from security researchers, who say the legislation raises “serious technical and security concerns.” Meanwhile, hacktivists protested by attacking the Web site of the industry group that most actively supports the proposal.

Earlier this month, the Senate Judiciary Committee passed the Preventing Real Online Threats to Economic Creativity and Theft of Intellectual Property Act (PDF), a bill offered by committee chairman, Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.), that would let the Justice Department obtain court orders requiring U.S. Internet service providers to filter customer access to domains found by courts to point to sites that are hosting infringing content. The bill envisions that ISPs would do this by filtering DNS requests for targeted domains. DNS, short for “domain name system,” transforms computer-friendly IP addresses (such as 94.228.133.163) into words that are easier for humans to remember. For example, typing “krebsonsecurity.com” into a browser brings you to 94.228.133.163, and vice versa.

But the idea of blocking piracy by asking ISPs to filter DNS requests has touched a nerve with several prominent security experts, who say it would be “minimally effective and would present technical challenges that could frustrate important security initiatives.” The comments came in a whitepaper sent to Senate leaders this month by DNS experts Steve Crocker, David Dagon, Dan Kaminsky, Danny McPherson and Paul Vixie. For a brief explanation of why these individuals are worth hearing from on this subject, see the “About the Authors” section at the end of their paper.

The Protect IP Act “would promote the development of techniques and software that circumvent use of the DNS,” the experts wrote. “These actions would threaten the DNS’s ability to provide universal naming, a primary source of the Internet’s value as a single, unified, global communications network.”

For now, the legislation is stalled, although Wired.com’s David Kravets notes that this is largely due to political — not technical — reasons: “Sen. Ron Wyden (D-Oregon) placed a hold on the measure, saying last week the bill “represents a threat to our economic future and to our international objectives.” The measure, however, was hailed by the content industry.”

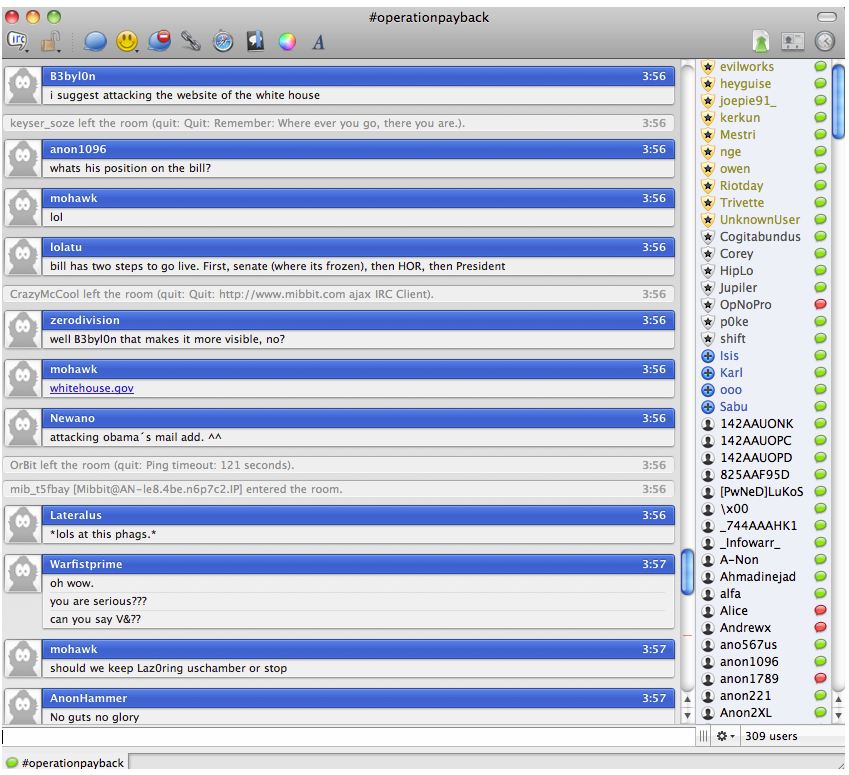

The bill’s current status in legislative limbo on the Senate floor wasn’t enough for unknown hackers who busied themselves over the long Memorial Day holiday weekend plotting ways to attack and disable Web sites belonging to supporters of the measure. The online property of one high-profile target — the U.S. Chamber of Commerce — was unreachable for most of the weekend. The site appears to be back up today. I asked the Chamber for comment on the outage, but have not received a response. The action appears to have been the work of Anonymous, the hacktivist group that called on followers last week to attack the Chamber’s site for its support of the bill.

KrebsOnSecurity will bring you further developments on this controversial legislation as they occur. Stay tuned.

So let me get this straight. This well-bribed tool of the studios wants every company, university, and college in the US to modify their DNS servers every time Eric “My People” Holder decides to seize another domain?

Under penalty of law?

Are our employers going to get paid for our time doing this?

@Kevin

I don’t claim to know how the minds of our lawmakers work, but I’ll guess that they think there’s only one central DNS server for the whole internet, so that all they have to do is wipe out the domain resolution on that one central server and voila – no more website.

It’s interesting that people are already planning alternate DNS services that would simply add onto whatever primary DNS you have – your ISP’s, your company’s, your organization’s, etc. Then, if you have this secondary DNS installed, if the domain name doesn’t resolve in the primary DNS, lookup proceeds to the secondary DNS. In principle, one could daisy chain multiple alternate DNS services.

But I don’t think the drafters of this law even understand how DNS works today, let alone what it could evolve into. *sigh*

Debby Does Dirty:

http://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=daisy+chain

Sorry, I took a little liberty with the normal meaning of “daisy-chain”:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daisy_chain_(information_technology)

“Some hardware can be attached to a computing system in a daisy chain configuration by connecting each component to another similar component, rather than directly to the computing system that uses the component.”

I didn’t think it was that much of a stretch to see how you could daisy-chain DNS services.

Somehow this bill seems to be in violation of the First admendment, or very near, near enough that even in these extremely partisan times, conservatives and liberals alike should agree that this is a dangerous bill, with wide ranging possibilities for civil rights issues. At best, it will be struck down if passed, at worst, parts of it will be stuck down.

The only thing that will prevent things like this is to pass a law that defines campaign contributions as the bribery that they are, and a felony offense.

It would be much cheaper for Congress to fix the problems identified in the Knujon Registrars report:

http://www.knujon.com/registrars/

But then Congress may not be able to comprehend such information. Most elected politicians are lawyers, so they see the world through a distorted viewpoint.

If Congress looked like America (teachers, doctors, blue collar, homeless, farmers, etc.) then perhaps their solutions would make more sense to Main Street.

I haven’t read the law proposal, but from Brian article I gather the intention is to make mandatory for american ISPs to intercept traffic over UDP/53 (DNS traffic), see if it’s a request concerning a blacklisted domain/site and if so, block it/send it to the bit bucket. This is of course stupid and will develop exactly as Steve Crocker, David Dagon, Dan Kaminsky, Danny McPherson and Paul Vixie said it will, by pushing alternative naming systems and fragmenting the Internet naming space.

This is the equivalent of going after phone companies for publishing phone books listing escort services. And what would this mean for the root DNS servers that the rest of the world uses? Would they have to comply as well?

And I’m guessing that the hackivists chose a method of DDoS that doesn’t utilize the DNS system. 😉

Currently ISPs have lots of authority to block traffic for any one reason, and give some other explanation for it when we call tech support.

Pricing of connections to the Internet are low for many services, because their support is sometimes low. Being mandated to do more might cost them X, in which they can jack up prices 10X, and tell customers that the increased pricing is to meet Congressional mandates.

How is this supposed to work?

1. Someone alleges some site is doing piracy, unable to get them to cease and desist via diplomacy.

2. Hire lawyers for court battle.

3. Lawyers get $ oodles.

4. Court battle, rules some site is doing piracy.

5. Justice dept maintains list of those sites, does not shut them down, by notifying the ONE ISP and ONE REGISTRAR that manages each problem site. Instead Justice dept informs millions of ISPs all over the world that they have to block access to those sites.

6. Each ISP implements blocking of the sites as ordered by the Justice dept, or calls their lawyers for court injunction fight Justice dept order, because the cost of implementation is a severe interference with their ability to do business.

7. Customers try to access the blocked sites, flood customer support of ISPs with questions why the connection is failing.

8. Other nations take the USA to a World Court of Justice for Unfair Trade practices.

Is there any risk of running out of DNS#s like phone#s in some cities, social security #s (because various strings of #s can’t be used because they are sexist or mark of Satan?).

I can see it now. Some DNS # is blocked because of bad stuff by the owner, so that owner goes to ISP to get another # which is not blocked yet, then no one has that DNS#, until some innocent new customer opens new account and gets it.

Like when a search is done on a street address … years ago, before you moved in, some drug dealer was arrested there, so now your record is forever linked to that felon.

There’s actually no such thing as a “DNS number (#)” as you put it that can run out or anything liek this.

What is being talked about here are DNS Servers. This has the function of matching an IP address (eg 94.228.133.163) to a domain name (eg. krebsonsecurity.com).

So when you type the URL krebsonsecurity.com your browser makes a query to a DNS Server which sends back 94.228.133.163. The IP is the “address” of the server that Brian’s blog is hosted on if you like.

So let’s say for arguments sake that Brian decide to give up blogging and become a practicing Yogi (hey, anythings possible!) and he sold the domain of this blog to someone else – in this case the person would likely have a new server and thus IP. So it’s really nothing like a physical house address.

“Is there any risk of running out of DNS#s like phone#s in some cities, social security #s (because various strings of #s can’t be used because they are sexist or mark of Satan?).”

While Neej is correct, “There’s actually no such thing as a “DNS number (#)” as you put it that can run out or anything liek this”, I gave you a thumbs up for the idea.

Even though the number portion of a DNS entry is an IP address, and it’s linked to the name of the domain (or, the hostname for the IP address), so technically there are no “DNS#s” as such, you’re absolutely right about the potential blacklisting of future domain names and harassing of their new owners.

And the way it would work is this. Government orders domain example.com banned. Registration for example.com lapses. Somebody else buys example.com and builds a website, but no one can access it by name because the government ban order is still in place for that domain name.

Sweet. And do you think anyone will put language in this bill to rescind the ban when the domain registration expires? That in itself is a knarly question, and no doubt would have to include processes to vet the new registrant for the domain name. And if they put all that in the bill, will there be a diligent bureaucracy in place to make sure that it gets done? What a hassle for the innocent new owner who just wants to name his website example.com.

Oops – before anybody trips me up on this – banning domain names would only work to begin with if DNS worked the way our lawmakers think it does, and it doesn’t.

But if they could do what they want to do, what I’ve described above would be only one of many unintended consequences.

Much graver unintended consequences, particularly for this group, would be the interference with DNS security proposals in the works. Way to go government – hamstringing efforts to make the internet more secure by making Man In the Middle attacks harder, all to protect copyright. (Just one example.)

“5. Justice dept maintains list of those sites, does not shut them down, by notifying the ONE ISP and ONE REGISTRAR that manages each problem site. Instead Justice dept informs millions of ISPs all over the world that they have to block access to those sites.”

I know Australian politicians are IT illiterate, and we are major sucks when it comes to United States copyright law, but I doubt that we would buy into blocking DNS because America told us to.

Even if we do, other countries will blatantly ignore America’s demands, who aren’t such sucks.

‘5. Justice dept maintains list of those sites, does not shut them down, by notifying the ONE ISP and ONE REGISTRAR that manages each problem site. Instead Justice dept informs millions of ISPs all over the world that they have to block access to those sites.’

How exactly is American Law supposed to have any slight affect on any other country in the world. Think something through before you post it.

I thought that was part of his point?

DNS filtering is easy to bypass .. just choose another DNS provider or edit your HOSTS file with manual entries. It doesn’t take much know-how to get round this type of filtering.

[PS, I think your target audience probably understand DNS quite well without having it explained 🙂 ]

Misty Morning…..appreciation in advance if you refrain from posting pron links…..this is an information on security and not a place for porn spam. The site name speaks clear…Urban.

It’s not like anyone is running a filesharing site on a shared IP address. The users would simply use the IP addresses to access them. They wouldn’t need DNS at all.

OK….the Federal Government will assume watch over servers and take action. Action along the lines of the can spam act. The same Government and attorney general that can’t control spending or our birders. By the time the red tape is unrolled and the defendant lawyers appeal, the bad guys will have found a work-around for their wares.

Brian, thanks for including the link to the white paper itself. It is a controversial issue, and, sadly, one that many Americans will never know exists because it has nothing to do with a kitty, celebrity, or the housing market bubble. So Congress will not get a lot of constituent input (not that they would listen to it) about this matter. I can’t claim to know enough about it to have a firm opinion yet, but does it make sense when I say that putting anything related to the Internet in the government’s control makes my skin crawl?

I may not be using the correct terminology, but where I work, we have been treating our IP whatever address like it is a street address.

Several end users have our IP address in software on PCs at home, or laptops, or whatever (we do NOT have a web site at present). Then there is turn over, some of it hostile, and Management asks how we block those people from access. Well we can disable their accounts, but when they were managers etc. they knew the access stuff on many people accounts, so we need to tell everyone to change passwords, but some access is not through a password system.

One thing we end up doing is getting a replacement IP “electronic street address” from our ISP, then notifying all authorized connectees what it is.

For security by obscurity reasons, I cannot divulge some details.

Something similar going on in Europe.

http://www.theregister.co.uk/2011/05/31/eu_data_law_clarke/

I hope I am not being off-topic here.

In the USA, each state has cyber security laws. The feds pass a much weaker law, which trumps all the states good laws.

In EU, each nation has privacy laws. EU passes weaker law, which trumps the individual nations protections.

EU law may choose between security, freedom and privacy, while member states were able to achieve all three. EU will be providing a ‘right to be forgotten’ whether people want it or not, and giving companies the right to store incorrect info on people, who either want correct info, or none at all. In other words, weakening EU protections to be consistent with USA law.

I don’t believe that federal laws automatically “trump” state laws in the U.S., but I know nothing about EU laws.

In the U.S., it’s my understanding that federal laws are minimums — a state law can be *stricter* than a federal law.

For example, say one state has no breach disclosure law and another state requires customer notification if electronic customer information is lost regardless of encryption. If a federal law is passed requiring notification when UNencrypted customer data is lost, then companies operating in the first state will now be required to comply to the new law, and companies in the second state will STILL have to comply with their older law.

I agree it is not automatic, but it is frequent.

There is a constant drumbeat of business complaints to Congress that the multiplicity of different state laws is a disruption to interstate commerce, that the nation (those businesses) needs a common set of rules, so Congress does a compromise, explicitly superseding the often stronger state legislation.

A business could comply with the strictest of all the states, for maximum consumer protection, but compliance is expensive, so it is much cheaper to lobby Congress, than to provide quality protection.

I remember the NO CALL LIST.

Indiana had a good system. I was using it.

Along came the federal law, which was both weaker than Indiana, and trumped the state laws.

The volume of unwanted phone calls increased, because now we getting phone spam permitted by the federal law, but prohibited under the former state law.

State law had said “If you do not already have a business relationship with the customer, do not call them.” Federal law allowed all sorts of exceptions, and the language was such to allow lots of wiggle room.

If DO NOT CALL is ever amended I would like a rule like this:

If you call someone with a recorded message promoting some product, service, upgrade, or whatever, and the customer does not accept your offer, then DO NOT CALL AGAIN with the identical offer for at least six months.

(I am getting, what sounds like phishing, or incompetent banking offer, maybe once a week. I now hang up every time. I have already spoken to my bank about it. Sorry, cannot stop it.)

There’s a reason you keep getting multiple calls for the same product – multiple dialers.

Read this comment section :

http://www.dailykos.com/comments/548274/20582757#c67?mode=alone;showrate=1#c67

click the top of the list comment – where it says “expert info here”

The scammers ignore all laws.

CAN-SPAM is another well-known example. California used to have a much stronger law prohibiting spam, but the federal law superseded it.

Brian,

Your readers may be interested in reading a statement ICANN’s Security & Stability Advisory Committee published last Saturday on DNS Blocking.

The statement attempts to turn the dialog regarding DNS filtering back to first principles, and in particular, the principle “First, do no harm”.

Quoting from the statement,

“Regardless of the mechanism used, organizations that implement blocking should apply these principles:

“1. The organization imposes a policy on a network and its users over which it exercises administrative control (i.e., it is the administrator of a policy domain).

“2. The organization determines that the policy is beneficial to its objectives and/or the interests of its users.

“3. The organization implements the policy using a technique that is least disruptive to its network operations and users, unless laws or regulations specify certain techniques.

“4. The organization makes a concerted effort to do no harm to networks or users outside its policy domain as a consequence of implementing the policy.

“When these principles are not applied, blocking using the DNS can cause significantly more collateral damage or unintended consequences with no remedy available to affected parties.”

These principles of course have broader application than Protect IP. Hopefully, those who are eager to turn DNS filtering into Maslow’s hammer may re-think this dubious tactic.

See http://www.icann.org/en/committees/security/sac050.pdf