Identity thieves stole tax and salary data from payroll giant ADP by registering accounts in the names of employees at more than a dozen customer firms, KrebsOnSecurity has learned. ADP says the incidents occurred because the victim companies all mistakenly published sensitive ADP account information online that made those firms easy targets for tax fraudsters.

Patterson, N.J.-based ADP provides payroll, tax and benefits administration for more than 640,000 companies. Last week, U.S. Bancorp (U.S. Bank) — the nation’s fifth-largest commercial bank — warned some of its employees that their W-2 data had been stolen thanks to a weakness in ADP’s customer portal.

Patterson, N.J.-based ADP provides payroll, tax and benefits administration for more than 640,000 companies. Last week, U.S. Bancorp (U.S. Bank) — the nation’s fifth-largest commercial bank — warned some of its employees that their W-2 data had been stolen thanks to a weakness in ADP’s customer portal.

ID thieves are interested in W-2 data because it contains much of the information needed to fraudulently request a large tax refund from the U.S. Internal Revenue Service (IRS) in someone else’s name. A reader who works at U.S. Bank shared a letter received from Jennie Carlson, the financial institution’s executive vice president of human resources.

“Since April 19, 2016, we have been actively investigating a security incident with our W-2 provider, ADP,” Carlson wrote. “During the course of that investigation we have learned that an external W-2 portal, maintained by ADP, may have been utilized by unauthorized individuals to access your W-2, which they may have used to file a fraudulent income tax return under your name.”

The letter continued:

“The incident originated because ADP offered an external online portal that has been exploited. For individuals who had never used the external portal, a registration had never been established. Criminals were able to take advantage of that situation to use confidential personal information from other sources to establish a registration in your name at ADP. Once the fraudulent registration was established, they were able to view or download your W-2.”

U.S. Bank spokesman Dana Ripley said the letter was sent to a “small population” of the bank’s more than 64,000 employees. Asked to comment on the letter from U.S. Bank, ADP confirmed that the fraud visited upon U.S. Bank also hit “a very small subset” of the ADP’s total customers this year.

ADP emphasized that the fraudsters needed to have the victim’s personal data — including name, date of birth and Social Security number — to successfully create an account in someone’s name. ADP also stressed that this personal data did not come from its systems, and that thieves appeared to already possess that data when they created the unauthorized accounts at ADP’s portal.

ADP Chief Security Officer Roland Cloutier said customers can choose to create an account at the ADP portal for each employee, or they can defer that process to a later date (but employers do have to chose one or the other, Cloutier said).

According to ADP, new users need to be in possession of two other things (in addition to the victim’s personal data) at a minimum in order to create an account: A custom, company-specific link provided by ADP, and a static code assigned to the customer by ADP.

The problem, Cloutier said, seems to stem from ADP customers that both deferred that signup process for some or all of their employees and at the same time inadvertently published online the link and the company code. As a result, for users who never registered, criminals were able to register as them with fairly basic personal info, and access W-2 data on those individuals.

U.S. Bank’s Ripley acknowledged that the bank published the link and company code to an employee resource online, but said the institution never considered that the data itself was privileged.

“We viewed the code as an identification code, not as an authentication code, and we posted it to a Web site for the convenience of our employees so they could access their W-2 information,” Ripley said. “We have discontinued that practice.”

In the meantime, ADP says it has developed systems to monitor the Web for any other customers that may inadvertently publish their signup link and code.

“We’ve now aggressively put in some security intelligence by trying to look for that code and turn off self-service registration access if we find that code” published online, Cloutier said.

ANALYSIS

ADP’s portal, like so many other authentication systems, relies entirely on static data that is available on just about every American for less than $4 in the cybercrime underground (SSN/DOB, address, etc). It’s true that companies should know better than to publish such a crucial link online along with the company’s ADP code, but then again these are pretty weak authenticators.

Cloutier said ADP does offer an additional layer of authentication — a personal identification code (PIC) — basically another static code that can be assigned to each employee. He added that ADP is trialing a service that will ask anyone requesting a new account to successfully answer a series of questions based on information that only the real account holder is supposed to know.

Cloutier declined to say who was providing the verification service, but these so-called knowledge-based authentication (KBA) or “out-of-wallet” questions generally focus on things such as previous address, loan amounts and dates and can be successfully enumerated with random guessing. In many cases, the answers can be found by consulting free online services, such as Zillow and Facebook.

The IRS found this out the hard way, and over the past year has removed two separate authentication systems that placed too much reliance on KBA and static data to authenticate taxpayers. In May 2015, the IRS took down its “Get Transcript” service after tax refund fraudsters began using it to pull W-2 data on more than 724,000 taxpayers. In those cases, the fraudsters also already had the victim’s SSN, DoB and other personal data. In March 2016, the IRS suspended its “Get IP PIN” feature for the same reason.

But somehow, KBA questions are an innovation that’s worth looking forward to at ADP.

“The IRS didn’t have a PIC code or client code,” Cloutier said when I brought up the IRS’s experience. “They didn’t have as many levels and individual authentication components that we provide our clients.”

Cloutier’s words recalled to mind a scene from the movie Office Space, in which Jennifer Aniston’s character is upbraided by her manager for wearing too few “pieces of flair” on her ‘Chotchkie’s’ uniform. His comment also made me think about one of the best scenes from the cult hit “This is Spinal Tap,” in which the character Nigel Tufnel shows off how all the knobs on his amplifier go to “level 11,” while other amps only go to the more boring and standard level 10.

It’s truly a measure of the challenges ahead in improving online authentication that so many organizations are still looking backwards to obsolete and insecure approaches. ADP’s logo includes the clever slogan, “A more human resource.” It’s hard to think of a more apt mission statement for the company. After all, it’s high time we started moving away from asking people to robotically regurgitate the same static identifiers over and over, and shift to a more human approach that focuses on dynamic elements for authentication. But alas, that’s fodder for a future post.

Update 1:59 p.m. ET: Clarified Spinal Tap reference.

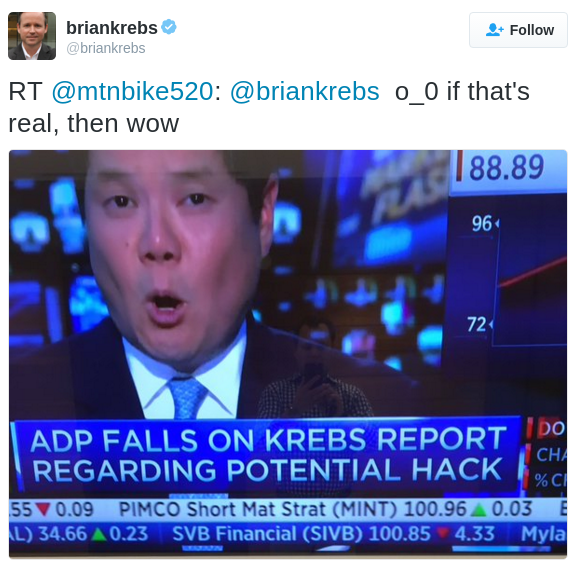

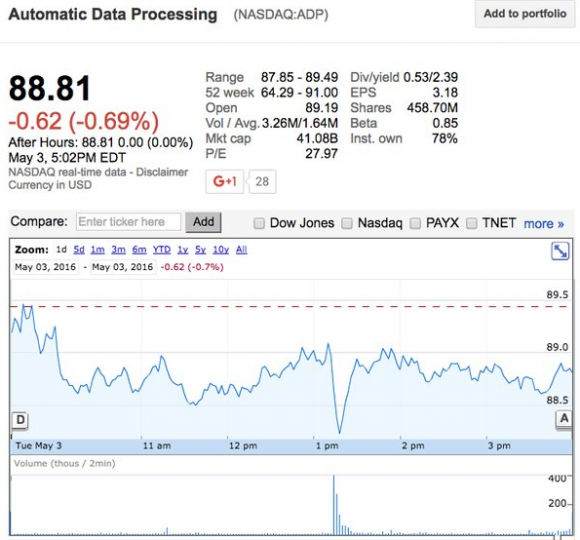

Update, 10:07 p.m. ET: It looks like ADP’s stock took a pretty big hit immediately after this story ran today.

The stock later rebounded:

Looking for clarification on some details. Did US Bank have SSO in place with ADP, or did they just direct their users with a link to the ADP public portal?

What is the risk profile for a company that has SSO in place with ADP?

Thanks.

I have no idea who tried to steal my taxes, but now I have one more possible culprit. Lucky for me/IRS, the place where they tried to direct deposit their fake return refused the deposit, and the IRS sent me a check, before I had even tried to file. At least the IRS pays better interest than my bank while they “investigate”.

I’ve been direct depositing to the same account for at least 10 years, and filing late in the year, you would think the IRS would take note of that before blindly sending a direct deposit to some thief’s account. And, whatever happened to all of the “know your customer” rules that banks are supposed to have before opening up such an account to receive the money? It seems that the accounts opened for tax anticipation loans must not need to know the customer. I can only hope some tax anticipation loan company is out the value of my fake return, and will improve their screening in the future.