Last week, KrebsOnSecurity detailed how BackConnect Inc. — a company that defends victims against large-scale distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks — admitted to hijacking hundreds of Internet addresses from a European Internet service provider in order to glean information about attackers who were targeting BackConnect. According to an exhaustive analysis of historic Internet records, BackConnect appears to have a history of such “hacking back” activity.

On Sept. 8, 2016, KrebsOnSecurity exposed the inner workings of vDOS, a DDoS-for-hire or “booter” service whose tens of thousands of paying customers used the service to launch attacks against hundreds of thousands of targets over the service’s four-year history in business.

Within hours of that story running, the two alleged owners — 18-year-old Israeli men identified in the original report — were arrested in Israel in connection with an FBI investigation into the shady business, which earned well north of $600,000 for the two men.

In my follow-up report on their arrests, I noted that vDOS itself had gone offline, and that automated Twitter feeds which report on large-scale changes to the global Internet routing tables observed that vDOS’s provider — a Bulgarian host named Verdina[dot]net — had been briefly relieved of control over 255 Internet addresses (including those assigned to vDOS) as the direct result of an unusual counterattack by BackConnect.

Asked about the reason for the counterattack, BackConnect CEO Bryant Townsend confirmed to this author that it had executed what’s known as a “BGP hijack.” In short, the company had fraudulently “announced” to the rest of the world’s Internet service providers (ISPs) that it was the rightful owner of the range of those 255 Internet addresses at Verdina occupied by vDOS.

In a post on NANOG Sept. 13, BackConnect’s Townsend said his company took the extreme measure after coming under a sustained DDoS attack thought to have been launched by a botnet controlled by vDOS. Townsend explained that the hijack allowed his firm to “collect intelligence on the actors behind the botnet as well as identify the attack servers used by the booter service.”

Short for Border Gateway Protocol, BGP is a mechanism by which ISPs of the world share information about which providers are responsible for routing Internet traffic to specific addresses. However, like most components built into the modern Internet, BGP was never designed with security in mind, which leaves it vulnerable to exploitation by rogue actors.

BackConnect’s BGP hijack of Verdina caused quite an uproar among many Internet technologists who discuss such matters at the mailing list of the North American Network Operators Group (NANOG).

BGP hijacks are hardly unprecedented, but when they are non-consensual they are either done accidentally or are the work of cyber criminals such as spammers looking to hijack address space for use in blasting out junk email. If BackConnect’s hijacking of Verdina was an example of a DDoS mitigation firm “hacking back,” what would discourage others from doing the same, they wondered?

“Once we let providers cross the line from legal to illegal actions, we’re no better than the crooks, and the Internet will descend into lawless chaos,” wrote Mel Beckman, owner of Beckman Software Engineering and a computer networking consultant in the Los Angeles area. “BackConnect’s illicit action undoubtedly injured innocent parties, so it’s not self defense, any more than shooting wildly into a crowd to stop an attacker would be self defense.”

A HISTORY OF HIJACKS

Townsend’s explanation seemed to produce more questions than answers among the NANOG crowd (read the entire “Defensive BGP Hijacking” thread here if you dare). I grew more curious to learn whether this was a pattern for BackConnect when I started looking deeper into the history of two young men who co-founded BackConnect (more on them in a bit).

To get a better picture of BackConnect’s history, I turned to BGP hijacking expert Doug Madory, director of Internet analysis at Dyn, a cloud-based Internet performance management company. Madory pulled historic BGP records for BackConnect, and sure enough a strange pattern began to emerge.

Madory was careful to caution up front that not all BGP hijacks are malicious. Indeed, my DDoS protection provider — a company called Prolexic Communications (now owned by Akamai Technologies) — practically invented the use of BGP hijacks as a DDoS mitigation method, he said.

In such a scenario, an organization under heavy DDoS attack might approach Prolexic and ask for assistance. With the customer’s permission, Prolexic would use BGP to announce to the rest of the world’s ISPs that it was now the rightful owner of the Internet addresses under attack. This would allow Prolexic to “scrub” the customer’s incoming Web traffic to drop data packets designed to knock the customer offline — and forward the legitimate traffic on to the customer’s site.

Given that BackConnect is also a DDoS mitigation company, I asked Madory how one could reasonably tell the difference between a BGP hijack that BackConnect had launched to protect a client versus one that might have been launched for other purposes — such as surreptitiously collecting intelligence on DDoS-based botnets and their owners?

Madory explained that in evaluating whether a BGP hijack is malicious or consensual, he looks at four qualities: The duration of the hijack; whether it was announced globally or just to the target ISP’s local peers; whether the hijacker took steps to obfuscate which ISP was doing the hijacking; and whether the hijacker and hijacked agreed upon the action.

For starters, malicious BGP attacks designed to gather information about an attacking host are likely to be very brief — often lasting just a few minutes. The brevity of such hijacks makes them somewhat ineffective at mitigating large-scale DDoS attacks, which often last for hours at a time. For example, the BGP hijack that BackConnect launched against Verdina lasted a fraction of an hour, and according to the company’s CEO was launched only after the DDoS attack subsided.

Second, if the party conducting the hijack is doing so for information gathering purposes, that party may attempt to limit the number ISPs that receive the new routing instructions. This might help an uninvited BGP hijacker achieve the end result of intercepting traffic to and from the target network without informing all of the world’s ISPs simultaneously.

“If a sizable portion of the Internet’s routers do not carry a route to a DDoS mitigation provider, then they won’t be sending DDoS traffic destined for the corresponding address space to the provider’s traffic scrubbing centers, thus limiting the efficacy of any mitigation,” Madory wrote in his own blog post about our joint investigation.

Thirdly, a BGP hijacker who is trying not to draw attention to himself can “forge” the BGP records so that it appears that the hijack was performed by another party. Madory said this forgery process often fools less experienced investigators, but that ultimately it is impossible to hide the true origin of forged BGP records.

Finally, in BGP hijacks that are consensual for DDoS mitigation purposes, the host under attack stops “announcing” to the world’s ISPs that it is the rightful owner of an address block under siege at about the same time the DDoS mitigation provider begins claiming it. When we see BGP hijacks in which both parties are claiming in the BGP records to be authoritative for a given swath of Internet addresses, Madory said, it’s less likely that the BGP hijack is consensual.

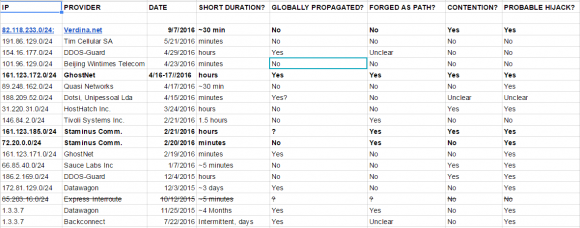

Madory and KrebsOnSecurity spent several days reviewing historic records of BGP hijacks attributed to BackConnect over the past year, and at least three besides the admitted hijack against Verdina strongly suggest that the company has engaged in this type of intel-gathering activity previously. The strongest indicator of a malicious and non-consensual BGP hijack, Madory said, were the ones that included forged BGP records.

Working together, Madory and KrebsOnSecurity identified at least 17 incidents during that time frame that were possible BGP hijacks conducted by BackConnect. Of those, five included forged BGP records. One was an hours-long hijack against Ghostnet[dot]de, a hosting provider in Germany.

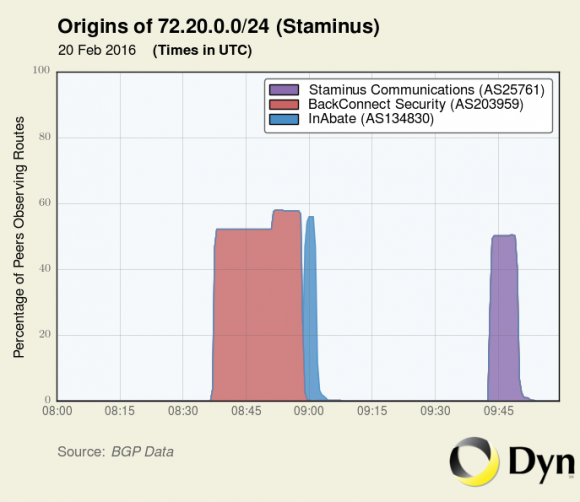

Two other BGP hijacks from BackConnect that included spoofed records were against Staminus Communications, a competing DDoS mitigation provider and a firm that employed BackConnect CEO Townsend for three years as senior vice president of business development until his departure from Staminus in December 2015.

“This hijack wasn’t conducted by Staminus. It was BackConnect posing as Staminus,” Dyn’s Madory concluded.

Two weeks after BackConnect hijacked the Staminus routes, Staminus was massively hacked. Unknown attackers, operating under the banner “Fuck ‘Em All,” reset all of the configurations on the company’s Internet routers, and then posted online Staminus’s customer credentials, support tickets, credit card numbers and other sensitive data. The intruders also posted to Pastebin a taunting note ridiculing the company’s security practices.

BackConnect’s apparent hijack of address space owned by Staminus Communications on Feb. 20, 2016. Image: Dyn.

POINTING FINGERS

I asked Townsend to comment on the BGP hijacks identified by KrebsOnSecurity and Dyn as having spoofed source information. Townsend replied that he could not provide any insight as to why these incidents occurred, noting that he and the company’s chief technology officer — 24-year-old Marshal Webb — only had access and visibility into the network after the company BackConnect Inc. was created on April 27, 2016.

According to Townsend, the current BackConnect Inc. is wholly separate from BackConnect Security LLC, which is a company started in 2014 by two young men: Webb and a 19-year-old security professional named Tucker Preston. In April 2016, Preston was voted out of the company by Webb and Townsend and forced to sell his share of the company, which was subsequently renamed BackConnect Inc.

“Before that, the original owner of BackConnect Security LLC was the only one that had the ability to access servers and perform any type of networking commands,” he explained. “We had never noticed these occurred until this last Saturday and the previous owner never communicated anything regarding these hijacks. Wish I could provide more insight, but Marshal and I do not know the reasons behind the previous owners decision to hijack those ranges or what he was trying to accomplish.”

In a phone interview, Preston told KrebsOnSecurity that Townsend had little to no understanding about the technical side of the business, and was merely “a sales guy” for BackConnect. He claims that Webb absolutely had and still has the ability to manipulate BackConnect’s BGP records and announcements.

Townsend countered that Preston was the only network engineer at the company.

“We had to self-learn how to do anything network related once the new company was founded and Tucker removed,” he said. “Marshal and myself didn’t even know how to use BGP until we were forced to learn it in order to bring on new clients. To clarify further, Marshal did not have a networking background and had only been working on our web panel and DDoS mitigation rules.”

L33T, LULZ, W00W00 AND CHIPPY

Preston said he first met Webb in 2013 after the latter admitted to launching DDoS attacks against one of Preston’s customers at the time. Webb had been painted with a somewhat sketchy recent history at the time — being fingered as a low-skilled hacker who went by the nicknames “m_nerva” and “Chippy1337.”

Webb, whose Facebook alias is “lulznet,” was publicly accused in 2011 by the hacker group LulzSec of snitching on the activities of the group to the FBI, claiming that information he shared with law enforcement led to the arrest of a teen hacker in England associated with LulzSec. Webb has publicly denied being an informant for the FBI, but did not respond to requests for comment on this story.

LulzSec members claimed that Webb was behind the hacking of the Web site for the video game “Deus Ex.” As KrebsOnSecurity noted in a story about the Deus Ex hack, the intruder defaced the gaming site with the message “Owned by Chippy1337.”

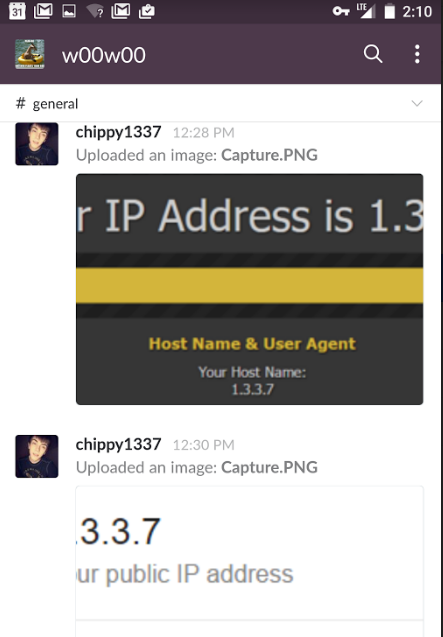

I was introduced to Webb at the Defcon hacking convention in Las Vegas in 2014. Since then, I have come to know him a bit more as a participant of w00w00, an invite-only Slack chat channel populated mainly by information security professionals who work in the DDoS mitigation business. Webb chose the handle Chippy1337 for his account in that Slack channel.

At the time, Webb was trying to convince me to take another look at Voxility, a hosting provider that I’ve previously noted has a rather checkered history and one that BackConnect appears to rely upon exclusively for its own hosting.

In our examination of BGP hijacks attributed to BackConnect, Dyn and KrebsOnSecurity identified an unusual incident in late July 2016 in which BackConnect could be seen hijacking an address range previously announced by Datawagon, a hosting provider with a rather dodgy reputation for hosting spammers and DDoS-for-hire sites.

That address range previously announced by Datawagon included the Internet address 1.3.3.7, which is hacker “leet speak” for the word “leet,” or “elite.” Interestingly, on the w00w00 DDoS discussion Slack channel I observed Webb (Chippy1337) offering other participants in the channel vanity addresses and virtual private connections (VPNs) ending in 1.3.3.7. In the screen shot below, Webb can be seen posting a screen shot demonstrating his access to the 1.3.3.7 address while logged into it on his mobile phone.

Webb, logged into the w00w00 DDoS discussion channel using his nickname “chippy1337,” demonstrating that his mobile phone connection was being routed through the Internet address 1.3.3.7, which BackConnect BGP hijacked in July 2016.

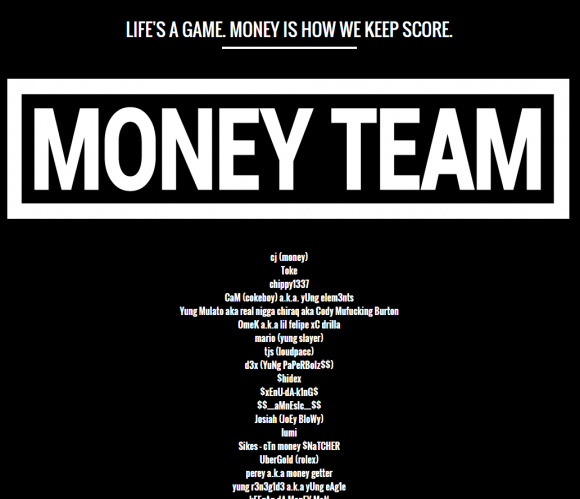

THE MONEY TEAM

The Web address 1.3.3.7 currently does not respond to browser requests, but it previously routed to a page listing the core members of a hacker group calling itself the Money Team. Other sites also previously tied to that Internet address include numerous DDoS-for-hire services, such as nazistresser[dot]biz, exostress[dot]in, scriptkiddie[dot]eu, packeting[dot]eu, leet[dot]hu, booter[dot]in, vivostresser[dot]com, shockingbooter[dot]com and xboot[dot]info, among others.

The Money Team comprised a group of online gaming enthusiasts of the massively popular game Counterstrike, and the group’s members specialized in selling cheats and hacks for the game, as well as various booter services that could be used to knock rival gamers offline.

Datawagon’s founder is an 18-year-old American named CJ Sculti whose 15-minutes of fame came last year in a cybersquatting dispute after he registered the domain dominos.pizza. A cached version of the Money Team’s home page saved by Archive.org lists CJ at the top of the member list, with “chippy1337” as the third member from the top.

Asked why he chose to start a DDoS mitigation company with a kid who was into DDoS attacks, Preston said he got to know Webb over several years before teaming up with him to form BackConnect LLC.

“We were friends long before we ever started the company together,” Preston said. “I thought Marshal had turned over a new leaf and had moved away from all that black hat stuff. He seem to stay true to that until we split and he started getting involved with the Datawagon guys. I guess his lulz mentality came back in a really stupid way.”

Townsend said Webb was never an FBI informant, and was never arrested for involvement with LulzSec.

“Only a search warrant was executed at his residence,” Townsend said. “Chippy is not a unique handle to Marshal and it has been used by many people. Just because he uses that handle today doesn’t mean any past chippy actions are his doing. Marshal did not even go by Chippy when LulzSec was in the news. These claims are completely fabricated.”

As for the apparent Datawagon hijack, Townsend said Datawagon gave BackConnect permission to announce the company’s Internet address space but later decided not to become a customer.

“They were going to be a client and they gave us permission to announce that IP range via an LOA [letter of authorization]. They did not become a client and we removed the announcement. Also note that the date of the screen shot you present of Marshal talking about the 1.3.3.7. is not even the same as when we announced Datawagons IPs.”

SOMETHING SMELLS BAD

When vDOS was hacked, its entire user database was leaked to this author. Among the more active users of vDOS in 2016 was a user who went by the username “pp412” and who registered in February 2016 using the email address mn@gnu.so.

The information about who originally registered the gnu.so domain has long been hidden behind WHOIS privacy records. But for several months in 2015 and 2016 the registration records show it was registered to a Tucker Preston LLC. Preston denies that he ever registered the gnu.so domain, and claims that he never conducted any booter attacks via vDOS. However, Preston also was on the w00w00 Slack channel along with Webb, and registered there using the email address tucker@gnu.so.

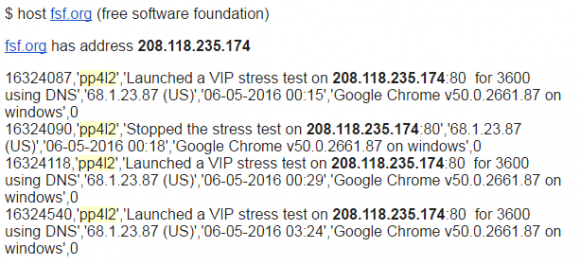

But whoever owned that pp412 account at vDOS was active in attacking a large number of targets, including multiple assaults on networks belonging to the Free Software Foundation (FSF).

Logs from the hacked vDOS attack database show the user pp4l2 attacked the Free Software Foundation in May 2016.

Lisa Marie Maginnis, until very recently a senior system administrator at the FSF, said the foundation began evaluating DDoS mitigation providers in the months leading up to its LibrePlanet2016 conference in the third week of March. The organization had never suffered any real DDoS attacks to speak of previously, but NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden was slated to speak at the conference, and the FSF was concerned that someone might launch a DDoS attack to disrupt the streaming of Snowden’s keynote.

“We were worried this might bring us some extra unwanted attention,” she said.

Maginnis said the FSF had looked at BackConnect and other providers, but that it ultimately decided it didn’t have time to do the testing and evaluation required to properly vet a provider prior to the conference. So the organization tabled that decision. As it happened, the Snowden keynote was a success, and the FSF’s fears of a massive DDoS never materialized.

But all that changed in the weeks following the conference.

“The first attack we got started off kind of small, and it came around 3:30 on a Friday morning,” Maginnis recalled. “The next Friday at about the same time we were hit again, and then the next and the next.”

The DDoS attacks grew bigger with each passing week, she said, peaking at more than 200 Gbps — more than enough to knock large hosting providers offline, let alone individual sites like the FSF’s. When the FSF’s Internet provider succeeded in blacklisting the addresses doing the attacking, the attackers switched targets and began going after larger-scale ISPs further upstream.

“That’s when our ISP told us we had to do something because the attacks were really starting to impact the ISP’s other customers,” Maginnis said. “Routing all of our traffic through another company wasn’t exactly an ideal situation for the FSF, but the other choice was we would just be disconnected and there would be no more FSF online.”

In August, the FSF announced that it had signed up with BackConnect to be protected from DDoS attacks, in part because the foundation only uses free software to perform its work, and BackConnect advertises “open source DDoS protection and security,” and it agreed to provide the service without charge.

The FSF declined to comment for this story. Maginnis said she can’t be sure whether the foundation will continue to work with BackConnect. But she said the timing of the attacks is suspicious.

“The whole thing just smells bad,” she said. “It does feel like there could be a connection between the DDoS and BackConnect’s timing to approach clients. On the other hand, I don’t think we received a single attack until Tucker [Preston] left BackConnect.”

DDoS attacks are rapidly growing in size, sophistication and disruptive impact, presenting a clear and present threat to online commerce and free speech alike. Since reporting about the hack of vDOS and the arrest of its proprietors nearly two weeks ago, KrebsOnSecurity.com has been under near-constant DDoS attack. One assault this past Sunday morning maxed out at more than 210 Gbps — the largest assault on this site to date.

Addressing the root causes that contribute to these attacks is a complex challenge that requires cooperation, courage and ingenuity from a broad array of constituencies — including ISPs, hosting providers, policy and hardware makers, and even end users.

In the meantime, some worry that as the disruption and chaos caused by DDoS attacks continues to worsen, network owners and providers may be increasingly tempted to take matters into their own hands and strike back at their assailants.

But this is almost never a good idea, said Rich Kulawiec, an anti-spam activist who is active on the NANOG mailing list.

“It’s tempting (and even trendy these days in portions of the security world which advocate striking back at putative attackers, never mind that attack attribution is almost entirely an unsolved problem in computing),” Kulawiec wrote. “It’s emotionally satisfying. It’s sometimes momentarily effective. But all it really does [is] open up still more attack vectors and accelerate the spiral to the bottom.”

KrebsOnSecurity would like to thank Dyn and Doug Madory for their assistance in researching the technical side of this story. For a deep dive into the BGP activity attributed to BackConnect, check out Madory’s post, BackConnect’s Suspicious Hijacks.

Tucker Preston is a very shady individual

Not nearly as shady as Marshal Webb though, the likely “mastermind” behind the illegal activities. The email address (mn@gnu.so) seems to implicate him (m_nerva) more than Tucker.

Nearly every person associated with anything related to DDoS seems to be a shady individual. DDoS attracts a wretched hive of scum and villainy.

Very interesting. You touched on the fact that BGP was easily manipulated, but didn’t follow through with the status of BGP going forward. Is there an effort to authenticate BGP broadcasts? More information would be appreciated!

disclaimer: I’m not involved in NANOG… Nor have I read many of the BGP RFCs, but some of them are probably relevant.

Here are a list of RFCs based on BGP: the Border Gateway Protocol Advanced Internet Routing Resources [0]:

[1] RFC 6039 Issues with Existing Cryptographic Protection Methods for Routing Protocols

[2] RFC 5123 Considerations in Validating the Path in BGP

[3] RFC 5065 Autonomous System Confederations for BGP

[4] RFC 5004 Avoid BGP Best Path Transitions from One External to Another

[5] RFC 4808 Key Change Strategies for TCP-MD5

[6] RFC 4698 IRIS: An Address Registry (areg) Type for the Internet Registry Information Service

Further reading:

[7] RFC 4272 BGP Security Vulnerabilities Analysis

[0] http://www.bgp4.as/rfc

[1] http://www.rfc-archive.org/getrfc.php?rfc=6039&tag=Issues-with-Existing-Cryptographic-Protection-Methods-for-Routing-Protocols

[2] http://www.rfc-archive.org/getrfc.php?rfc=5123&tag=Considerations-in-Validating-the-Path-in-BGP

[3] http://www.rfc-archive.org/getrfc.php?rfc=5065&tag=Autonomous-System-Confederations-for-BGP

[4] http://www.rfc-archive.org/getrfc.php?rfc=5004&tag=Avoid-BGP-Best-Path-Transitions-from-One-External-to-Another

[5] http://www.rfc-archive.org/getrfc.php?rfc=4808&tag=Key-Change-Strategies-for-TCP-MD5

[6] http://www.rfc-archive.org/getrfc.php?rfc=4698&tag=IRIS–An-Address-Registry-%28areg%29-Type-for-the-Internet-Registry-Information-Service

[7] http://www.rfc-archive.org/getrfc.php?rfc=4272&tag=BGP-Security-Vulnerabilities-Analysis

It isn’t going to change anytime soon. Good ISPs won’t allow customers to announce just any network. They first verify that the customer is actually assigned that network in the LIR/RIR, and then and only then add it to the filter of networks which a customer can announce. This works in an honest and ethical world. The Internet goes beyond this to many shady places.

There is a standard to try to protect against this. I’ve not read it, but I would assume the LIR/RIR will sign a record basically giving the assigned entity authority to announce it. This would protect against forgery. Unfortunately, no BGP routers speak this language (yet):

http://packetpushers.net/bgpsec-signatures-performance/

Yes, RPKI, but adoption is doing pretty much as well as DNSSEC, and for similar reasons.

Seems like a cautionary tale along the lines of “The enemy of my enemy may not be my enemy yet not be a friend either, and should probably never be considered as fully a friend or completely trustworthy.”

As always, great reporting Brian.

Unfortunately, as with most of these kinds of stories, the important take-aways, both for policy makers and for the public at large, kind-of get lost in the shuffle.

One of these is that the smallest unit of IPv4 address space that can, in practice, be hijacked is a so-called /24 block of consecutive addresses. Such a block consists of exactly 256 consecutive addresses. Thankfully, it is still somewhat rare that any such block of addresses is inhabited entirely and exclusively by bad actors. The implication is that BGP hijacking of the type you’ve described WILL, in general, result in some collateral damage to innocents, and perhaps even a lot of that.

Also, of course, on the other side of the ledger, strong DDoS attacks quite frequently impact many of the nearby neighbors of the actual intended victim, in many cases taking down entire ISPs.

As at least a couple of people noted in the NANOG mailing list thread you provided a pointer to, self-regulation in the Internet industry simply has not worked. It has not worked to stop hijacks, it hasn’t worked to stop DDoS attacks, and it hasn’t worked to stop spamming, hacking, etc. So one naturally is forced to wonder “Where are the grownups?”

I suspect that the Tier 1 backbones, if they elected to work together, could rapidly stomp out all of these problems. So the question then becomes “Why don’t they?” It may be for fear of being dragged into some sort of hypothetical future anti-trust litigation, but more probably it is just simple economics. They’ve probably done the calculations and concluded that they’ll make more money by just allowing all of this nonsense to continue. Certainly, the more DDoS attacks that occur, the more everyone needs additional bandwidth to try to defend against those, and this ever-increasing need for bandwidth probably suits all of the sellers of bandwidth just fine.

I don’t see any of this ending well, or even ending without government intervention, as odious as that may be. The best analogy that comes immediately to mind is that the Tier 1 backbones are, in effect, selling both guns and bullet-proof vests, and then kicking back and sipping champaign in their luxury condos in Vail while the Interent for the rest of us slides inexorably into chaos.

I have never got any joy from tier 1 operators, that is for sure – no cooperation at all. It’s like they see no responsibility about what comes across their backbone at all.

I agree. Where are the grownups? How have we let something as critical as the Internet remain so unregulated that 20 year olds with shady (at best) histories can gain sufficient access to get away with launching a BGP hijack? Why don’t the Tier 1 backbones, or ICANN, or some other authority step in and control this?

Agreed.

Having done a bit of research on the the subject of ICANN many months ago, it’s not a principle of ICANN to secure the Internet in such a way. Specifically, lookup the policy of the Internet Society, part of ICANN: “…Internet… sustain an open and universally accessible…”, for badness also.

As far as I’m concerned the Internet Society and ICANN is another part of the nefarious operation of the Internet.

I suggest creating a petition, or sign this one from many months ago:

https://www.change.org/p/icann-internet-corporation-for-assigned-names-and-numbers-tell-the-worldwide-internet-maintainers-to-disconnect-select-networks-in-china-from-the-internet-internet-2-0

Just taking the name of his product, backconnect, is a popular name for reverse-proxy systems found in botnets. Hes most likely an individual who plays both sides, as we commonly see in the cybersecurity world.

Sorry not product, *company

I’m pretty sure mn@gnu.so is for m_nerva,

Excellent reporting Krebs! You went beyond what i expected!

I hope now the FSF gets rid of Backconnect and audits their systems.

There is something that still bothers me, so backconnect took control of vdos before the FBI supposedly arrested them, yet:

Not a single statement from the FBI.

Not a single picture or anything valuable from the media.

On hackforums some resellers and people very close to vdos just claimed they have “sold” their booters and that they’ve been told to stop.

What the hell? We’re still missing a piece of the story here i think.

I found some articles saying they’re under house arrest.

Still it seems like Backconnect knew in advance what was going on.

The israeli police didn’t and won’t dig into the whole thing.

I hope the FBI looks into the network of booters floating around vdos as only the owners have been arrested. Many of the techies and resellers are safe, just going to wait some time until they appear again with new domains, nicknames.. And of course with websites well hidden behind Cloudflare.

655Gbps DDoS against Krebs to try and silence this story, BackConnect must be quite upset with you! Impressive mitigation by Akamai though

*665Gbps, share some stats/graphs if possible!

Mr. Krebs,

I respectfully suggest that you use more clear terminology. Your misuse of the term “BGP hijack” muddies the waters and unnecessarily distracts the real issue, which is _malicious_ attacks on innocent Internet users. A consensual BGP redirect is not a BGP hijack, anymore than you consensually letting your friend drive your car is a car hijack. DoS protection services do not redirect their customers’ BGP advertisements without prior permission, and typically not without RADB documentation.

You could readily edit your story to substitute “legal BGP redirects” wherever you talk about what you confusingly call “consensual BGP hijacks”.

Here come the inevitable nits from the NANOG crowd. If there’s one thing that’s painfully clear from reading that NANOG thread is that there is no law which outlaws BGP hijacks. Hence no legal/illegal hijacks. There’s a reason the terminology is flexible.

Can someone get me an invite to w00w00.slack.com?

If you’re going to take that position, then “hijack” is the wrong word to use altogether. The term literally means “an illegal seizure” — check any dictionary. It has this meaning in the IT community as well.

It’s not a nit. I’d think that as a journalist you would consider it a matter of professionalism to communicate clearly. I know I do.

sometimes it’s up to the reader to do their homework, but it’s nitpickers like you that go off on tangents, wasting comment space except for .001% of the readers

Brian, I think Mel has a valid point to distinguish the normal operations from ‘hijacking’.

Different framing may show the problems with BGP more clearly as the difference is mainly lack of consent coupled with a procedure that effectively enables non consensual routing changes.

That said, I believe you are both correct, and to all the good actors I highly recommend limiting friendly fire.

Regards

This. It isn’t a technical nit, it is quite simply using clear terminology. When one has a contract & consent, it isn’t a hijack. All hijacks are bad, mmm’kay?

It might be noted that Tucker Preston is an unlikely, though not impossible, name, shared with a curious industrialist and automaker.

Marshal Webb, especially with one L and web with two B’s is a little on point, too, for an internet security firm. At least it’s not Marshal Dillon.

I don’t know about Bryant, but Townsend is the name of James Mason’s character in North By Northwest, who isn’t really what he seems, either, as Cary Grants find out.

It’s amazing to me just how lame some people are, to spend all their time being a dick to strangers for a few bucks, while screwing over their future selves (abet blind to it).

Sounds more like drug addict behavior than techs.

BackConnect, Marshall and Tucker are hilariously shady and tried selling DDoS services to people actively getting hit.

Out of nowhere two s-kids have an ex-Staminus ‘take over the company’ and re-incorporate it after he leaves Staminus.

What I find most interesting is Townsend talks about collecting & getting intel from the BGP hijack of vDOS, at the same time, when BackConnect first came online, they hijacked Staminus’ management network thread.

Makes us wonder what intel they collected from Bryan Townsend’s former employer when they hijacked Staminus’ own management IPs, likely the root passwords.

Golf clap for Mr. Krebs. FINALLY exposing some of his filthy peers. Or rather, scumbags in infosec. One big cesspool.

Of course Townsend had Webb destroy Staminus and a hundred other things. This crap has been going on for years and there’s a hundred more like them. Essentially fake companies as they’re nothing as a cover for all sorts of other garbage. Like selling ddos protection that you buy or get ddos’d. It’s Mafia type extortion. Only the medium as changed.

Welcome back to the web.

‘Twitter feeds which report on large-scale changes to the global Internet routing tables ‘ Do you have a link ?

I’m not intending this as a troll. The reason I left NANOG in the first place is the prevalent attitude of osmosis and head in the sand when it comes to this very issue. Back in 98-2001 I was working for Pacific Bell Internet at the time and we were already monitoring ddos attacks in the 100’s of mbit which was a lot at that time. The primary recipients were, of course, IRC servers.

I remember attending SANS in 2000 where the Trinoo DDOS network was first revealed and I subsequently had a private chat with Stephen Northcutt of SANS regarding the issue of DDOS. Several of us, those involved with both NANOG and SANS, agreed that the problem would only get worse over the years. Here you go ladies and gentlemen of NANOG and Tier1 providers. Your neckbeard arrogance, wonton cluelessness, and “that’s not my problem” attitude has brought us to this. I know how to solve this ‘lack of action’ attitude. We need more military style leadership that is willing to make the tough decision and take action. Something that NANOG has repeatedly shown that its unwilling or incapable of doing.

Briefly digging into Webb and Preston yielded lots of shady activity. A winding tale of counterstrike server hosting, DDoS attacks and “mitigation”, and accusations all along the way. I’d post it all here but it’s not exactly hidden. And Townsend being a former employee of Staminus AND founder & CEO of BackConnect!!! You throw in the BGP hijack and the subsequent hack of Staminus and it all starts feeling very Mr Robot. Trying to wear the grey hat can make a mess of your opsec.