The COVID-19 epidemic has brought a wave of email phishing attacks that try to trick work-at-home employees into giving away credentials needed to remotely access their employers’ networks. But one increasingly brazen group of crooks is taking your standard phishing attack to the next level, marketing a voice phishing service that uses a combination of one-on-one phone calls and custom phishing sites to steal VPN credentials from employees.

According to interviews with several sources, this hybrid phishing gang has a remarkably high success rate, and operates primarily through paid requests or “bounties,” where customers seeking access to specific companies or accounts can hire them to target employees working remotely at home.

And over the past six months, the criminals responsible have created dozens if not hundreds of phishing pages targeting some of the world’s biggest corporations. For now at least, they appear to be focusing primarily on companies in the financial, telecommunications and social media industries.

“For a number of reasons, this kind of attack is really effective,” said Allison Nixon, chief research officer at New York-based cyber investigations firm Unit 221B. “Because of the Coronavirus, we have all these major corporations that previously had entire warehouses full of people who are now working remotely. As a result the attack surface has just exploded.”

TARGET: NEW HIRES

A typical engagement begins with a series of phone calls to employees working remotely at a targeted organization. The phishers will explain that they’re calling from the employer’s IT department to help troubleshoot issues with the company’s virtual private networking (VPN) technology.

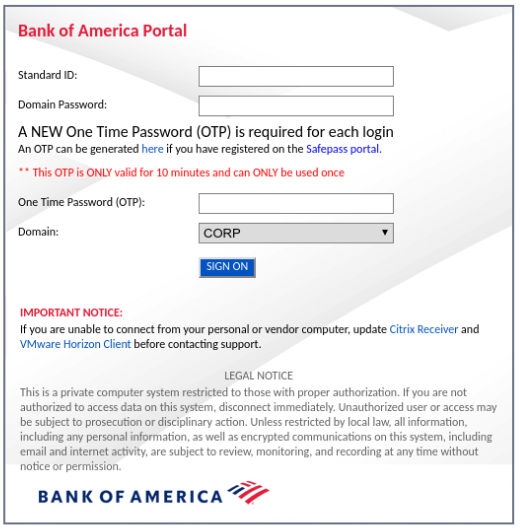

The employee phishing page bofaticket[.]com. Image: urlscan.io

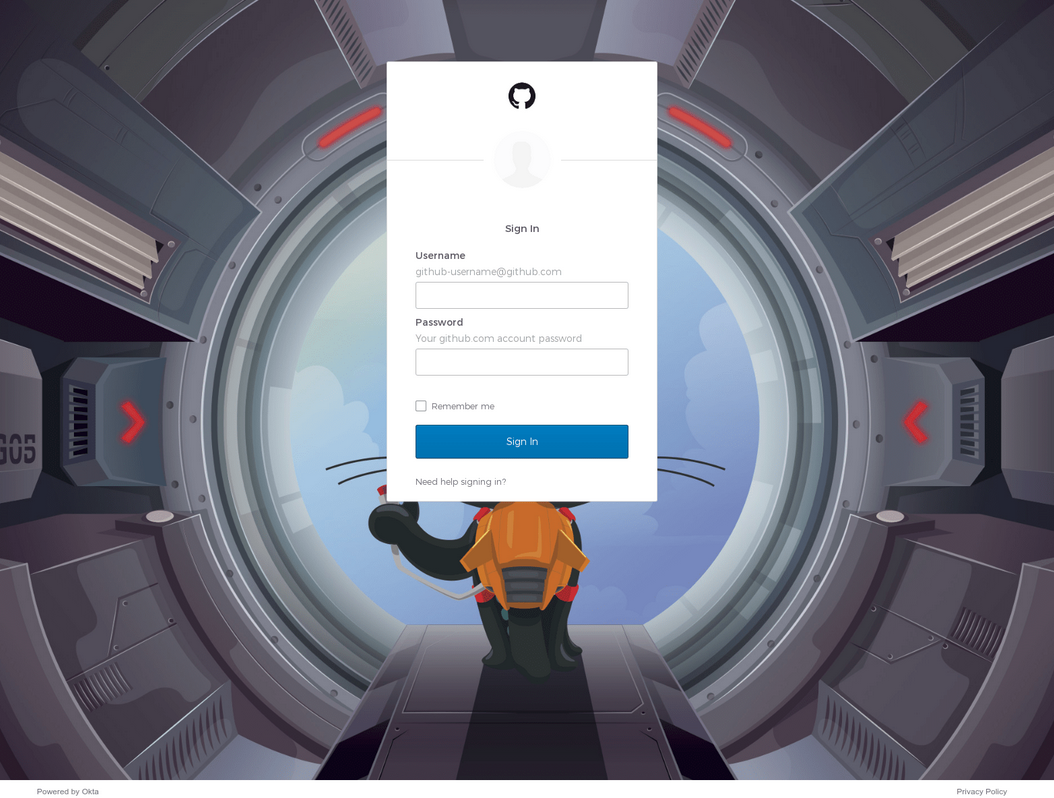

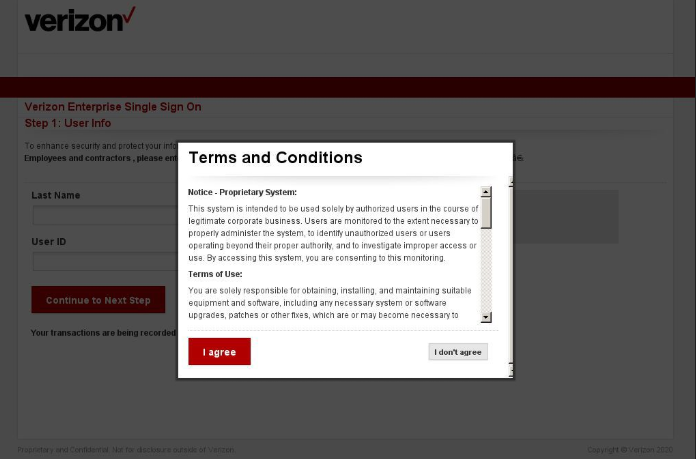

The goal is to convince the target either to divulge their credentials over the phone or to input them manually at a website set up by the attackers that mimics the organization’s corporate email or VPN portal.

Zack Allen is director of threat intelligence for ZeroFOX, a Baltimore-based company that helps customers detect and respond to risks found on social media and other digital channels. Allen has been working with Nixon and several dozen other researchers from various security firms to monitor the activities of this prolific phishing gang in a bid to disrupt their operations.

Allen said the attackers tend to focus on phishing new hires at targeted companies, and will often pose as new employees themselves working in the company’s IT division. To make that claim more believable, the phishers will create LinkedIn profiles and seek to connect those profiles with other employees from that same organization to support the illusion that the phony profile actually belongs to someone inside the targeted firm.

“They’ll say ‘Hey, I’m new to the company, but you can check me out on LinkedIn’ or Microsoft Teams or Slack, or whatever platform the company uses for internal communications,” Allen said. “There tends to be a lot of pretext in these conversations around the communications and work-from-home applications that companies are using. But eventually, they tell the employee they have to fix their VPN and can they please log into this website.”

SPEAR VISHING

The domains used for these pages often invoke the company’s name, followed or preceded by hyphenated terms such as “vpn,” “ticket,” “employee,” or “portal.” The phishing sites also may include working links to the organization’s other internal online resources to make the scheme seem more believable if a target starts hovering over links on the page.

Allen said a typical voice phishing or “vishing” attack by this group involves at least two perpetrators: One who is social engineering the target over the phone, and another co-conspirator who takes any credentials entered at the phishing page and quickly uses them to log in to the target company’s VPN platform in real-time.

Time is of the essence in these attacks because many companies that rely on VPNs for remote employee access also require employees to supply some type of multi-factor authentication in addition to a username and password — such as a one-time numeric code generated by a mobile app or text message. And in many cases, those codes are only good for a short duration — often measured in seconds or minutes.

But these vishers can easily sidestep that layer of protection, because their phishing pages simply request the one-time code as well.

Allen said it matters little to the attackers if the first few social engineering attempts fail. Most targeted employees are working from home or can be reached on a mobile device. If at first the attackers don’t succeed, they simply try again with a different employee.

And with each passing attempt, the phishers can glean important details from employees about the target’s operations, such as company-specific lingo used to describe its various online assets, or its corporate hierarchy.

Thus, each unsuccessful attempt actually teaches the fraudsters how to refine their social engineering approach with the next mark within the targeted organization, Nixon said.

“These guys are calling companies over and over, trying to learn how the corporation works from the inside,” she said.

NOW YOU SEE IT, NOW YOU DON’T

All of the security researchers interviewed for this story said the phishing gang is pseudonymously registering their domains at just a handful of domain registrars that accept bitcoin, and that the crooks typically create just one domain per registrar account.

“They’ll do this because that way if one domain gets burned or taken down, they won’t lose the rest of their domains,” Allen said.

More importantly, the attackers are careful to do nothing with the phishing domain until they are ready to initiate a vishing call to a potential victim. And when the attack or call is complete, they disable the website tied to the domain.

This is key because many domain registrars will only respond to external requests to take down a phishing website if the site is live at the time of the abuse complaint. This requirement can stymie efforts by companies like ZeroFOX that focus on identifying newly-registered phishing domains before they can be used for fraud.

“They’ll only boot up the website and have it respond at the time of the attack,” Allen said. “And it’s super frustrating because if you file an abuse ticket with the registrar and say, ‘Please take this domain away because we’re 100 percent confident this site is going to be used for badness,’ they won’t do that if they don’t see an active attack going on. They’ll respond that according to their policies, the domain has to be a live phishing site for them to take it down. And these bad actors know that, and they’re exploiting that policy very effectively.”

A phishing page (github-ticket[.]com) aimed at siphoning credentials for a target organization’s access to the software development platform Github. Image: urlscan.io

SCHOOL OF HACKS

Both Nixon and Allen said the object of these phishing attacks seems to be to gain access to as many internal company tools as possible, and to use those tools to seize control over digital assets that can quickly be turned into cash. Primarily, that includes any social media and email accounts, as well as associated financial instruments such as bank accounts and any cryptocurrencies.

Nixon said she and others in her research group believe the people behind these sophisticated vishing campaigns hail from a community of young men who have spent years learning how to social engineer employees at mobile phone companies and social media firms into giving up access to internal company tools.

Traditionally, the goal of these attacks has been gaining control over highly-prized social media accounts, which can sometimes fetch thousands of dollars when resold in the cybercrime underground. But this activity gradually has evolved toward more direct and aggressive monetization of such access.

On July 15, a number of high-profile Twitter accounts were used to tweet out a bitcoin scam that earned more than $100,000 in a few hours. According to Twitter, that attack succeeded because the perpetrators were able to social engineer several Twitter employees over the phone into giving away access to internal Twitter tools.

Nixon said it’s not clear whether any of the people involved in the Twitter compromise are associated with this vishing gang, but she noted that the group showed no signs of slacking off after federal authorities charged several people with taking part in the Twitter hack.

“A lot of people just shut their brains off when they hear the latest big hack wasn’t done by hackers in North Korea or Russia but instead some teenagers in the United States,” Nixon said. “When people hear it’s just teenagers involved, they tend to discount it. But the kinds of people responsible for these voice phishing attacks have now been doing this for several years. And unfortunately, they’ve gotten pretty advanced, and their operational security is much better now.”

A phishing page (vzw-employee[.]com) targeting employees of Verizon. Image: DomainTools

PROPER ADULT MONEY-LAUNDERING

While it may seem amateurish or myopic for attackers who gain access to a Fortune 100 company’s internal systems to focus mainly on stealing bitcoin and social media accounts, that access — once established — can be re-used and re-sold to others in a variety of ways.

“These guys do intrusion work for hire, and will accept money for any purpose,” Nixon said. “This stuff can very quickly branch out to other purposes for hacking.”

For example, Allen said he suspects that once inside of a target company’s VPN, the attackers may try to add a new mobile device or phone number to the phished employee’s account as a way to generate additional one-time codes for future access by the phishers themselves or anyone else willing to pay for that access.

Nixon and Allen said the activities of this vishing gang have drawn the attention of U.S. federal authorities, who are growing concerned over indications that those responsible are starting to expand their operations to include criminal organizations overseas.

“What we see now is this group is really good on the intrusion part, and really weak on the cashout part,” Nixon said. “But they are learning how to maximize the gains from their activities. That’s going to require interactions with foreign gangs and learning how to do proper adult money laundering, and we’re already seeing signs that they’re growing up very quickly now.”

WHAT CAN COMPANIES DO?

Many companies now make security awareness and training an integral part of their operations. Some firms even periodically send test phishing messages to their employees to gauge their awareness levels, and then require employees who miss the mark to undergo additional training.

Such precautions, while important and potentially helpful, may do little to combat these phone-based phishing attacks that tend to target new employees. Both Allen and Nixon — as well as others interviewed for this story who asked not to be named — said the weakest link in most corporate VPN security setups these days is the method relied upon for multi-factor authentication.

A U2F device made by Yubikey, plugged into the USB port on a computer.

One multi-factor option — physical security keys — appears to be immune to these sophisticated scams. The most commonly used security keys are inexpensive USB-based devices. A security key implements a form of multi-factor authentication known as Universal 2nd Factor (U2F), which allows the user to complete the login process simply by inserting the USB device and pressing a button on the device. The key works without the need for any special software drivers.

The allure of U2F devices for multi-factor authentication is that even if an employee who has enrolled a security key for authentication tries to log in at an impostor site, the company’s systems simply refuse to request the security key if the user isn’t on their employer’s legitimate website, and the login attempt fails. Thus, the second factor cannot be phished, either over the phone or Internet.

In July 2018, Google disclosed that it had not had any of its 85,000+ employees successfully phished on their work-related accounts since early 2017, when it began requiring all employees to use physical security keys in place of one-time codes.

Probably the most popular maker of security keys is Yubico, which sells a basic U2F Yubikey for $20. It offers regular USB versions as well as those made for devices that require USB-C connections, such as Apple’s newer Mac OS systems. Yubico also sells more expensive keys designed to work with mobile devices. [Full disclosure: Yubico was recently an advertiser on this site].

Nixon said many companies will likely balk at the price tag associated with equipping each employee with a physical security key. But she said as long as most employees continue to work remotely, this is probably a wise investment given the scale and aggressiveness of these voice phishing campaigns.

“The truth is some companies are in a lot of pain right now, and they’re having to put out fires while attackers are setting new fires,” she said. “Fixing this problem is not going to be simple, easy or cheap. And there are risks involved if you somehow screw up a bunch of employees accessing the VPN. But apparently these threat actors really hate Yubikey right now.”

Super article , Thanks

I’m thinking that phone based app verification as MFA is a close second in terms of security strength compared to Yubikey type devices?

Nope, because TOTP codes (which is what the apps like Google Authenticator and similar) provide aren’t immune to the replay – the real web site doesn’t cannot tell the difference between the code typed into it directly, or being passed to it from the bad actor’s web site.

Close to Yubikey security, but done as an app on the phone, would be something like Duo push authentication. The Duo app does show details like “where” (geographic location) the user appears to be authenticating from. But, the user would have to pay attention to the prompt, and not just acknowledge it.

Additional option is for the employer is to use something like Duo (which will provide the GeoIP lookup of the remote auth request) and detect a change. But, not all VPN portals aren’t super-flexible like that, and this is a fair bit of coding, but now support folks will have to deal with the consequent issues.

RG: I don’t quite understand your comment about “replay”. Google’s authenticator rotates the code very quickly, about every 30 seconds. If you don’t put the correct code in within that time frame, you fail. Wouldn’t it be very unlikely that a user could enter the google username/password and authenticator code into the phishing site, then ALSO have the bad guy use it within that timeframe? Heck, I often have a hard time entering it into my SSO app within that time.

The attacker isn’t involved, code she wrote is doing the work for her at scale. She merely receives the authenticated session tokens from the app, which are often refreshable for a long time if not forever.

I think RG may have said “replay’ when they meant to say “MITM”.

Awesome article Brian. The physical key requirement is a tall order for large companies that you have mentioned in your article. But that cost is miniscule compared to the cost of being penetrated. Thank you!

When you think of the HUGE money the corporations are saving by giving up renting office space, and letting the employees work from home; the cost of the key is pocket change in comparison; and maybe the difference is even larger than that. You can’t exaggerate too much when it is the difference between thousands of dollars and millions or maybe even billions of dollars of infrastructure savings.

Never underestimate the power of penny wise, but pound foolish thinking in the corporate world. It is the reason that infosec departments are chronically underfunded. “How does it help the bottom line?” If it wasn’t for compliance obligations like PCI most companies would spend diddly on their cyber security.

So true this statement. A society/company/individual that does not focus on cyber security education today is a society/company/individual that chose to get vulnerable and hacked tomorrow.

Brian,

Thank you for the ongoing great work.

Logical outcome of increasing sophistication of attackers. Neither voice calling or phishing pages is new – combining the two is.

I got a Yubikey as a Wired.com promotion. They work great, and it is no hassle to use.

It also avoids using a cell phone as part of the 2FA authorization. I changed cell phones and it was a hassle and a half to get into godaddy in order to deal with a criminal that infiltrated to use some services on my account that I did not order and that they made no attempt to verify.

My only problem is that not enough places use it.

Indian Rediff makes a good point. Now if we could just change the laws to that all the costs stuck to the company, then the bean counters would wise up.

I’ve heard good things and… well, no bad ones about these keys.

My understanding of their technology is limited but what prevents an attacker who manages to get malcode on the desktop/app level (through spear-v/phishing in this case or any) from just accessing the key directly as if a legitimate request from the unknowing user?

Well, I can’t really speak as to Yubikey’s proprietary (H?)OTP system (only available on their black keys), but for U2F, the key is designed to never give out its internal secrets, for any reason, ever.

It’s also designed to only respond to authentication requests when the user performs some action (as part of the “authentication ceremony”, usually tapping a button on the U2F key). That would require an attacker to get the user to keep pressing the button every time.

Now, if an attacker could install a root cert that they control onto the victim’s machine, then a MITM attack might be possible. But at that point, they’re having to intercept the victim’s traffic in real time to impersonate the real domain.

Another real good article .

So the corporate VPNs don’t use certificates? All I know is openvpn.

Great article… but I’m still surprised to see hardware tokens being recommended as the fallback… they authenticate possession and are cumbersome and costly to manage insofar as distribution are concerned.

Behavioral analytics driven by keystroke dynamics would have stopped these hackers from gaining access to Twitter. They are frictionless for users, don’t require hardware, are easy to deploy and very cost effective. Every Twitter employee could have been protected with this for less than the cost of a cup of coffee per month for each user.

Wouldn’t keystroke dynamics be susceptible to an attacker recording the timings of the users’ key strokes on their phishing logon page and simply playing them back at the same rate on the company’s real login page?

When people start getting hired to clean up the sewer rats of the internet, posting videos of their demise, these crimes will slow down. Until then, laws don’t discourage, and punishment is a vacation if anything. Roll in the mercenaries to hunt them. I would like this job.

Yeah somehow I don’t think you’re a mercenary. #Hunch

How about you stay in school and learn to resist scammer requests.

If you’re sending bitcoin or your VPN credentials, you failed.

The real problem is too-trusting fools, less so the wolves themselves.

Fix that problem, be an actual hero.

I am not a merc (lol), but it certainly doesn’t prevent me from wanting to punish thieves. I’m retiring soon, so not contributing in that way much longer, long done with formal school. I like that you’re promoting people being smarter, but that doesn’t excuse the behavior of scum, and will not denture it. I understand your victim blaming for people that don’t lock their doors they don’t know exist (yes that is what it is) Criminals don’t steal because it’s easy, they steal because that is who they are. You may not understand it, most good people can’t comprehend it, but some people are just bad/evil and need to be removed.

Physical & hardware tokens only work if there is a lockout and the problem with that is that the legitimate user can be deliberately locked out. Social engineers use this weakness to get around these devices.

Machine Certificates FTW. We have been using these for years and if you have a cert deployed on the endpoint in order to log into the VPN, coupled with strong controls to limit access to that certificate, even a phished user won’t allow a bad actor to access the VPN.

As someone who now on a daily basis works on real users vpn problems because they don’t understand how to properly update the password when they are working from home and locking themselves out I can see this working with a very high percentage because probably some users they are calling do have real VPN issues.

It would also be helpful if the phone system stopped allowing spoofed phone numbers.

I think ppl let their guard down for US teenage hack3rs cuz they figure no1 is dumb enough to perpetrate this kinda cybercrime within the reach of US law enforcement (unlike in China and NK).

Good article. Yes, I have read up on token security. And I remember my reading of security researchers, that token based systems can be broken into.

One, never assume that the person entering your system, is a money grubbing teenager. The client may be someone important, especially to your bottom line. No client, no bottom line.

Two, why do so many people, have access to your resources, even client resources, is that wise? Is it safe? Is it necessary?

Three, remote access has been busted many times by the major players, it’s not as secure as everyone thinks,

Voice calling + phishing pages is definitely a step up in sophistication. I can definitely see it working on some stressed out remote workers who are barely hanging on to their jobs.

Thanks for the timely information Brian, and as usual informative and in-depth.

For the past some months I’ve been getting 20-30 phishing emails a month, which I can immediately tell from the subject line. ‘Account has been locked’ or ‘Account has been suspended’.

In trying to do my tiny part in this battle against criminals, what I’m doing is: I put the message in forwarding mode, copy the fake domain name part after the @, go over to whois.com which tells me the Registrar of that domain name, then forward the email to abuse@domainregistrar and cc to abuse@amazon, or abuse@paypal, etc. Yesterday, I had one message that came from the Govt. of Chile’s domain. Could not find the abuse address for them.

I’m seeing a lot of these bot-created fake domains being done at godaddy, webnic, register, name, web and even at Outlook.

While I get a canned responses from Amazon, GoDaddy and MS, there’s no word from the rest of them.

I’m wondering if anyone is doing anything with the information I’m forwarding to them?

I think it is worth noting that it is not just the initial cost of the Yubikeys that a company needs to pay – in my experience, the Yubikeys can be somewhat fragile compared to the typical 600 lb gorilla user. When the Yubikey is put on a key ring, it will get knocked around A LOT and the keys will then fail. That means the IT department needs to now deal with pissed-off remote user that can’t login, and it will require a replacement key. One solution is to buy every employee TWO Yubikeys, one they carry with them, and one they store in a more protected place. So, now you have doubled the cost for the company. And, of course, you also need to make sure the user has enrolled both Yubikeys. We have not had good luck getting non-tech savvy users to properly enroll their HW keys, which means you need to have enough IT support to handle these issues.

Webauthn lets chrome use the biometrics on the device, if that’s useful at all

My biggest threat is mainly from older users or recent hires who aren’t familiar with how the company works.

Older users are often not on the ball, so they can fall for dumb phishing tricks. On the other hand they’re less likely to receive an email from “IT Department” filled with weird grammar and spelling errors and take it seriously since they know we deal with things one on one.

New hires fall for the “IT Department” emails because they think that’s how everyone does things and haven’t yet gotten up to speed that we deal with everyone one on one because we’re small enough to make that happen. On the other hand they’re usually younger and less likely to fall for Stupid Phishing Tricks.

I highly doubt anyone’s going to be calling our folks and spoofing their way past someone on a phone call. Everyone knows everyone and knows everyone else’s voice, and we have no recent hires due to the epidemic (just rehires).

So other than your ageist bias, do you have actual evidence that demonstrates “older users are often not on the ball” more than anyone else? What defines an “older user”?

It is not “older users” that are the problem, it is simply users that won’t learn – and in my (ahem) considerable experience, those users are all ages.

“Recipients may only share TLP:AMBER information with members of their own organization, and with clients or customers who need to know the information to protect themselves or prevent further harm. Sources are at liberty to specify additional intended limits of the sharing: these must be adhered to.”

This is a huge risk to all organisations, when it comes to multifactor authentication devices I like Yubikey but there are some good alternatives too such as Nitrokey and SoloKeys both of which are open source.