The New York Times this week published a fascinating story about a young programmer in Ukraine who’d turned himself in to the local police. The Times says the man did so after one of his software tools was identified by the U.S. government as part of the arsenal used by Russian hackers suspected of hacking into the Democratic National Committee (DNC) last year. It’s a good read, as long as you can ignore that the premise of the piece is completely wrong.

The story, “In Ukraine, a Malware Expert Who Could Blow the Whistle on Russian Hacking,” details the plight of a hacker in Kiev better known as “Profexer,” who has reportedly agreed to be a witness for the FBI. From the story:

“Profexer’s posts, already accessible to only a small band of fellow hackers and cybercriminals looking for software tips, blinked out in January — just days after American intelligence agencies publicly identified a program he had written as one tool used in Russian hacking in the United States. American intelligence agencies have determined Russian hackers were behind the electronic break-in of the Democratic National Committee.”

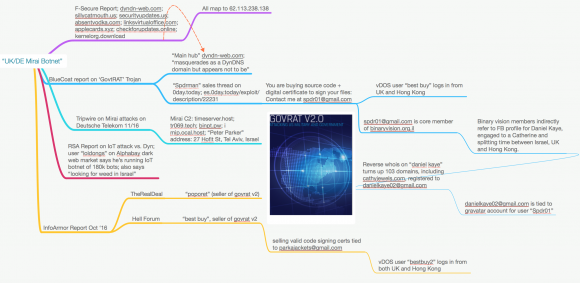

The Times’ reasoning for focusing on the travails of Mr. Profexer comes from the “GRIZZLYSTEPPE” report, a collection of technical indicators or attack “signatures” published in December 2016 by the U.S. government that companies can use to determine whether their networks may be compromised by a number of different Russian cybercrime groups.

The only trouble is nothing in the GRIZZLYSTEPPE report said which of those technical indicators were found in the DNC hack. In fact, Prefexer’s “P.A.S. Web shell” tool — a program designed to insert a digital backdoor that lets attackers control a hacked Web site remotely — was specifically not among the hacking tools found in the DNC break-in.

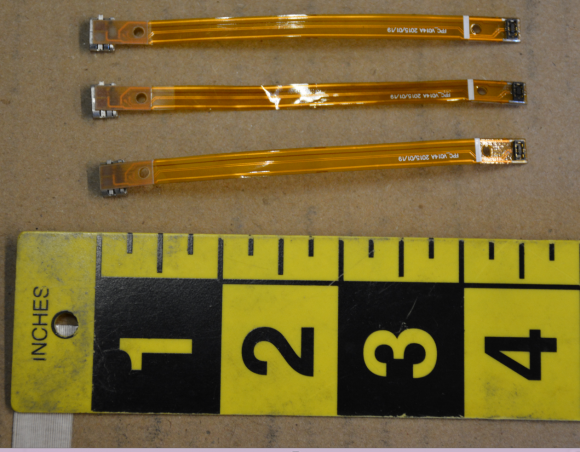

![The P.A.S. Web shell, as previously offered for free on the now-defunct site profexer[dot]name.](https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/pas30.png)

The P.A.S. Web shell, as previously offered for free on the now-defunct site profexer[dot]name.

That’s according to

Crowdstrike, the company called in to examine the DNC’s servers following the intrusion. In a statement released to KrebsOnSecurity, Crowdstrike said it

published the list of malware that it found was used in the DNC hack, and that the Web shell named in the New York Times story was not on that list.

Robert M. Lee is founder of the industrial cybersecurity firm Dragos, Inc. and an expert on the challenges associated with attribution in cybercrime. In a post on his personal blog, Lee challenged The Times on its conclusions.

“The GRIZZLYSTEPPE report has nothing to do with the DNC breach though and was a collection of technical indicators the government compiled from multiple agencies all working different Russian related threat groups,” Lee wrote.

“The threat group that compromised the DNC was Russian but not all Russian groups broke into the DNC,” he continued. “The GRIZZLYSTEPPE report was also highly criticized for its lack of accuracy and lack of a clear message and purpose. I covered it here on my blog but that was also picked up by numerous journalists and covered elsewhere [link added]. In other words, there’s no excuse for not knowing how widely criticized the GRIZZLYSTEPPE report was before citing it as good evidence in a NYT piece.”

Perhaps in response to Lee’s blog post, The Times issued a correction to the story, re-writing the above-quoted and indented paragraph to read:

“It is the first known instance of a living witness emerging from the arid mass of technical detail that has so far shaped the investigation into the election hacking and the heated debate it has stirred. The Ukrainian police declined to divulge the man’s name or other details, other than that he is living in Ukraine and has not been arrested.”

[Side note: Profexer may well have been doxed by this publication just weeks after the GRIZZLYSTEPPE report was released.] Continue reading →

As noted in

As noted in ![The P.A.S. Web shell, as previously offered for free on the now-defunct site profexer[dot]name.](https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/pas30.png)

More than two dozen of the vulnerabilities fixed in today’s Windows patch bundle address “critical” flaws that can be exploited by malware or miscreants to assume complete, remote control over a vulnerable PC with little or no help from the user.

More than two dozen of the vulnerabilities fixed in today’s Windows patch bundle address “critical” flaws that can be exploited by malware or miscreants to assume complete, remote control over a vulnerable PC with little or no help from the user. In

In