Virtually every aspect of cybercrime has been made into a service or plug-and-play product. That includes dating scams — among the oldest and most common of online swindles. Recently, I had a chance to review a package of dating scam emails, instructions, pictures, videos and love letter templates that are sold to scammers in the underground, and was struck by how commoditized this type of fraud has become.

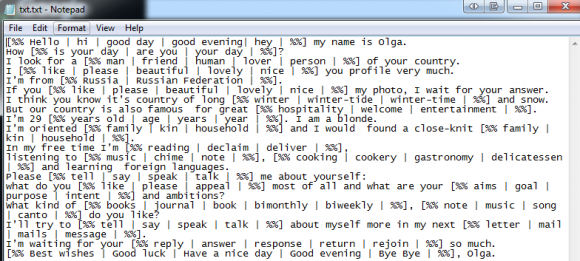

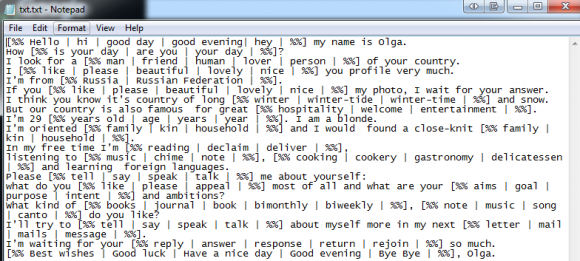

The dating scam package is assembled for and marketed to Russian-speaking hackers, with hundreds of email templates written in English and a variety of European languages. Many of the sample emails read a bit like Mad Libs or choose-your-own-adventure texts, featuring decision templates that include advice for ultimately tricking the mark into wiring money to the scammer.

The romance scam package is designed for fraudsters who prey on lonely men via dating Web sites and small spam campaigns. The vendor of the fraud package advertises a guaranteed response rate of at least 1.2 percent, and states that customers who average 30 scam letters per day can expect to earn roughly $2,000 a week. The proprietor also claims that his method is more than 20% effective within three replies and over 60% effective after eight.

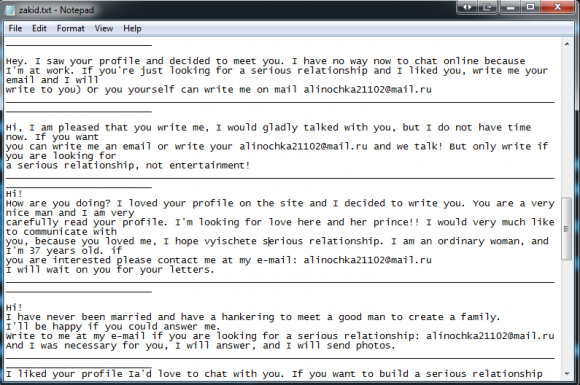

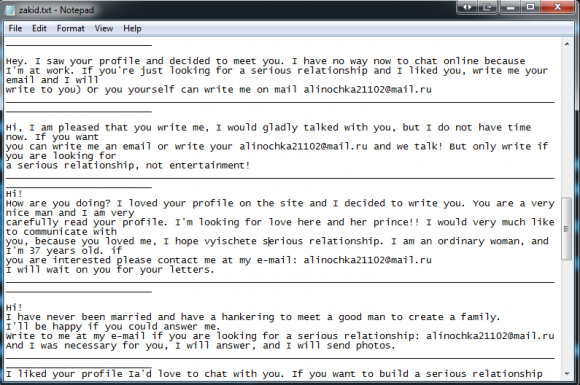

One of hundreds of sample template files in the dating scam package.

The dating scam package advises customers to stick to a tried-and-true approach. For instance, scammers are urged to include an email from the mother of the girl in the first 10 emails between the scammer and a target. The scammer often pretends to be a young woman in an isolated or desolate region of Russia who is desperate for a new life, and the email from the girl’s supposed mother is intended to add legitimacy to the scheme.

Then there are dozens of pre-fabricated excuses for not talking on the phone, an activity reserved for the final stretch of the scam when the fraudster typically pretends to be stranded at the airport or somewhere else en route to the target’s home town.

“Working with dozens of possible outcomes, they carefully lay out every possible response, including dealing with broke guys who fell in love online,” said Alex Holden, the security expert who intercepted the romance scam package. “If the mark doesn’t have money, the package contains advice for getting him credit, telling the customer to restate his love and discuss credit options.”

A sample letter with multiple-choice options for creating unique love letter greetings.

Interestingly, although Russia is considered by many to be among the most hostile countries toward homosexuals, the makers of this dating scam package also include advice and templates for targeting gay men.

Also included in the dating scam tutorial is a list of email addresses and pseudonyms favored by anti-scammer vigilantes who try to waste the scammers’ time and otherwise prevent them from conning real victims. In addition, the package bundles several photos and videos of attractive Russian women, some of whom are holding up blank signs onto which the scammer can later Photoshop whatever message he wants.

Holden said that an enterprising fraudster with the right programming skills or the funds to hire a coder could easily automate the scam using bots that are programmed to respond to emails from the targets with content-specific replies.

CALL CENTERS TO CLOSE THE DEAL

The romance scam package urges customers to send at least a dozen emails to establish a rapport and relationship before even mentioning the subject of traveling to meet the target. It is in this critical, final part of the scam that the fraudster is encouraged to take advantage of criminal call centers that staff women who can be hired to play the part of the damsel in distress.

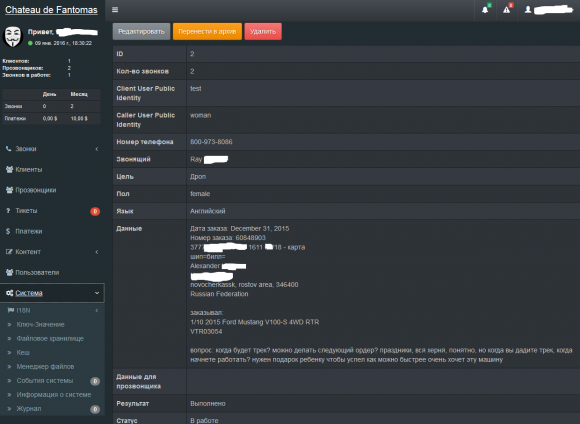

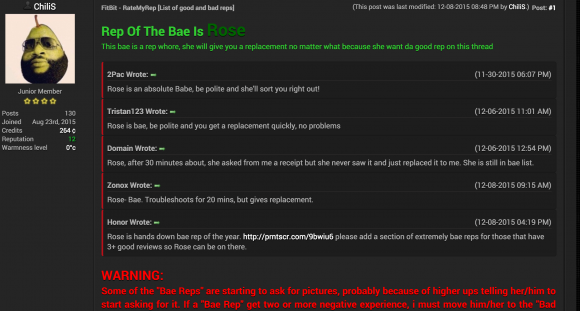

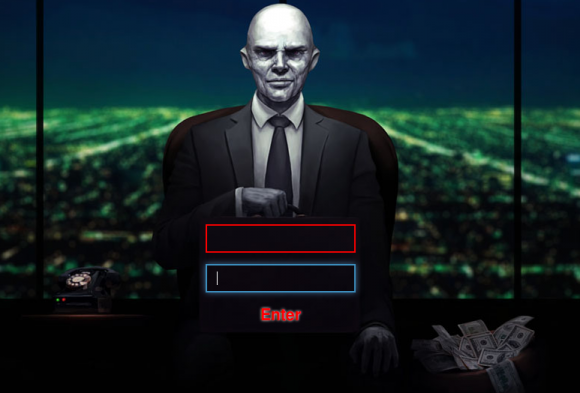

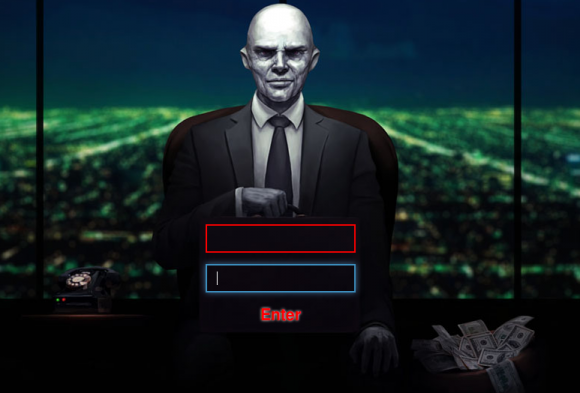

The login page for a criminal call center.

“When you get down to the final stage, there has to be a crisis, some compelling reason why the target should you send the money,” said Holden, founder of Hold Security [full disclosure: Yours Truly is an uncompensated adviser to Holden’s company]. “Usually this is something like the girl is stranded at the airport or needs money to get a travel visa. There has to be some kind of distress situation for this person to be duped into wiring money, which can be anywhere between $200 and $2,000 on average.” Continue reading →

At issue is a cyber insurance policy issued to Houston-based Ameriforge Group Inc. (doing business as “AFGlobal Corp.“) by Federal Insurance Co., a division of insurance giant Chubb Group. AFGlobal maintains that the policy it held provided coverage for both computer fraud and funds transfer fraud, but that the insurer nevertheless denied a claim filed in May 2014 after scammers impersonating AFGlobal’s CEO convinced the company’s accountant to wire $480,000 to a bank in China.

At issue is a cyber insurance policy issued to Houston-based Ameriforge Group Inc. (doing business as “AFGlobal Corp.“) by Federal Insurance Co., a division of insurance giant Chubb Group. AFGlobal maintains that the policy it held provided coverage for both computer fraud and funds transfer fraud, but that the insurer nevertheless denied a claim filed in May 2014 after scammers impersonating AFGlobal’s CEO convinced the company’s accountant to wire $480,000 to a bank in China. In

In  Toni Casala found this out the hard way. Casala’s firm — Children in Film — works as an advocate for young actors and their families. The company’s entire operations run off of application hosting services at a managed cloud solutions firm in California, from QuickBooks to Microsoft Office and Outlook. Employees use Citrix to connect to the cloud, and the hosting firm’s application maps the cloud drive as a local disk on the user’s hard drive.

Toni Casala found this out the hard way. Casala’s firm — Children in Film — works as an advocate for young actors and their families. The company’s entire operations run off of application hosting services at a managed cloud solutions firm in California, from QuickBooks to Microsoft Office and Outlook. Employees use Citrix to connect to the cloud, and the hosting firm’s application maps the cloud drive as a local disk on the user’s hard drive. Six of the nine patches Microsoft is pushing out today address flaws the software giant considers “critical,” meaning the vulnerabilities could be exploited by malware or miscreants to break into vulnerable computers remotely without any help from users. The critical updates tackle problems with

Six of the nine patches Microsoft is pushing out today address flaws the software giant considers “critical,” meaning the vulnerabilities could be exploited by malware or miscreants to break into vulnerable computers remotely without any help from users. The critical updates tackle problems with