Buying a car or making any other expensive purchase can be a hassle. And when it’s necessary to finance a purchase, there’s one more hurdle. If you want merchant financing, you’ll often be required to fill out a credit application or, at the least, to provide information like a credit card or your Social Security number.

Recent hacker break-ins at a half-dozen car dealerships nationwide are a reminder of just how easily one’s personal and financial information can be jeopardized by poor security at any of of tens of thousands of organizations that have access to that data.

Earlier this month, Farmington Hills, Mich. based RouteOne LLC sent a letter to more than 20,000 dealerships around the country, warning of probable malware infections at six dealerships that use its service. Formed in 2002, RouteOne is a joint venture by GMAC (now called Ally Financial), Ford Motor Credit, Toyota Financial Services, and DaimlerChrysler Financial Services. Dealerships use RouteOne’s credit application software and Web portal to run credit checks and process financing for car buyers. The service also allows authorized users to pull credit reports from the three major credit reporting bureaus.

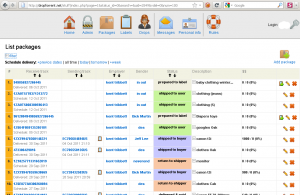

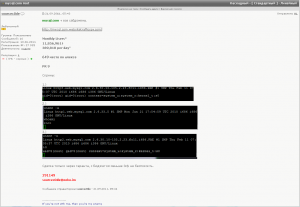

In September 2011, RouteOne issued a “security bulletin,” to its affiliates, stating in part:

A letter from RouteOne to partner dealerships.

“Over the recent past, RouteOne has received information regarding a small number of dealerships (6) that have experienced compromises in their system security environments (including misappropriation and misuse of their RouteOne log on credentials likely as a result of their dealership computers being infected with spyware). RouteOne is in contact and working with affected dealerships in an attempt to help them address their security issues.”

The bulletin states further than RouteOne “takes these matters very seriously and therefore has been in contact with the FBI and the U.S. Secret Service. Ryan Holmes, the Secret Service agent assigned to the investigation of the attacks on RouteOne’s customers, said he could not release any information on an active investigation.

Mass data collection, and the resulting potential for cybertheft, is a relatively recent problem. Ten years ago, data aggregation points like RouteOne didn’t exist. RouteOne was created to speed credit and financing processes at dealerships, which previously had to navigate to and authenticate at multiple finance vendors, lenders and credit bureaus. Today, dealerships can access all this information with a username and password at RouteOne.net, or via a RouteOne iPhone app.

Dan Doman, vice president and general counsel for RouteOne, said the company became aware of the unauthorized activity after it was notified by the affected dealers.

“It’s important to note that RouteOne has not been breached in this instance, or ever in the past,” Doman said. “What we do when we learn of these matters is we try to get it out to our dealers as quickly as possible so they can take appropriate steps to fix it.”

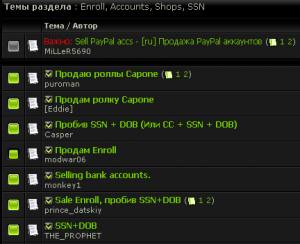

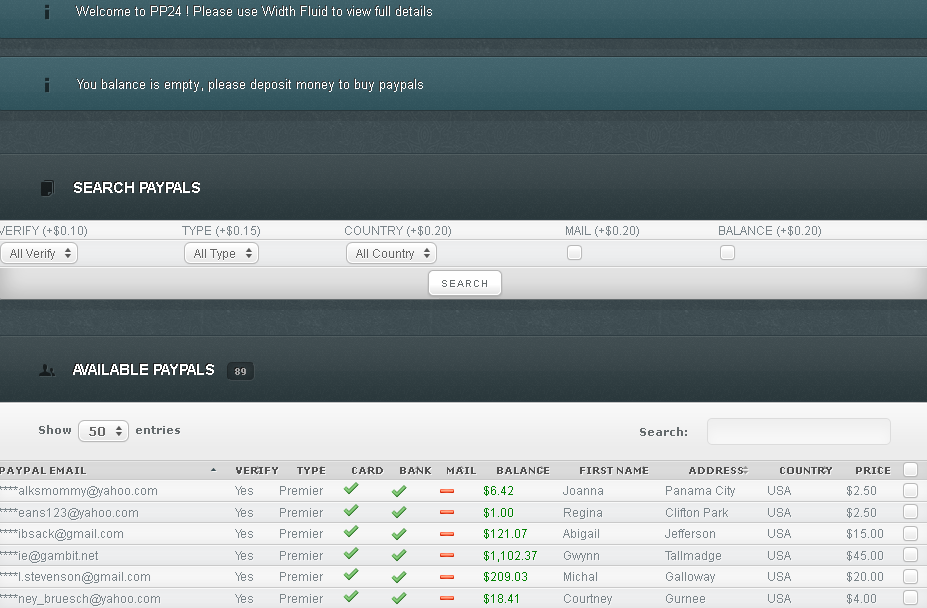

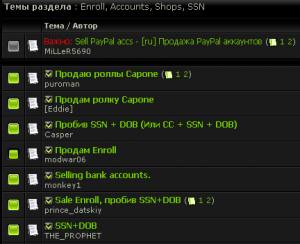

ID theft services for sale.

Technically, RouteOne is correct. It did not have a data breach: Some of the customers who use their service did. But that distinction is irrelevant to thieves who prize such access, and to consumers who find their identities hijacked and themselves saddled with unexpected debts from fraudulent new lines of credit opened in their names. The criminal underground is full of services that allow miscreants to look up Social Security numbers, dates of birth, maiden names, and other sensitive information. It’s not clear where that data comes from, but the most likely sources are compromised accounts at businesses and organizations that have easy and frequent access to consumer data.

This blog post isn’t intended to single out RouteOne; that is just a recent example of a vast problem for individuals who must share personal data. The same kind of data aggregation exists in many other businesses and tens of thousands of organizations that routinely access sensitive consumer data, including medical, dental and real estate services. Thieves can access a gold mine of consumer data just by compromising PCs at any of these places. Continue reading →