One of the oldest scams around — the fake job interview that seeks only to harvest your personal and financial data — is on the rise, the FBI warns. Here’s the story of a recent LinkedIn impersonation scam that led to more than 100 people getting duped, and one almost-victim who decided the job offer was too-good-to-be-true.

Last week, someone began posting classified notices on LinkedIn for different design consulting jobs at Geosyntec Consultants, an environmental engineering firm based in the Washington, D.C. area. Those who responded were told their application for employment was being reviewed and that they should email Troy Gwin — Geosyntec’s senior recruiter — immediately to arrange a screening interview.

Gwin contacted KrebsOnSecurity after hearing from job seekers trying to verify the ad, which urged respondents to email Gwin at a Gmail address that was not his. Gwin said LinkedIn told him roughly 100 people applied before the phony ads were removed for abusing the company’s terms of service.

“The endgame was to offer a job based on successful completion of background check which obviously requires entering personal information,” Gwin said. “Almost 100 people applied. I feel horrible about this. These people were really excited about this ‘opportunity’.”

Erica Siegel was particularly excited about the possibility of working in a creative director role she interviewed for at the fake Geosyntec. Siegel said her specialty — “consulting with start ups and small businesses to create sustainable fashion, home and accessories brands” — has been in low demand throughout the pandemic, so she’s applied to dozens of jobs and freelance gigs over the past few months.

On Monday, someone claiming to work with Gwin contacted Siegel and asked her to set up an online interview with Geosyntec. Siegel said the “recruiter” sent her a list of screening questions that all seemed relevant to the position being advertised.

Siegel said that within about an hour of submitting her answers, she received a reply saying the company’s board had unanimously approved her as a new hire, with an incredibly generous salary considering she had to do next to no work to get a job she could do from home.

Worried that her potential new dream job might be too-good-to-be-true, she sent the recruiter a list of her own questions that she had about the role and its position within the company.

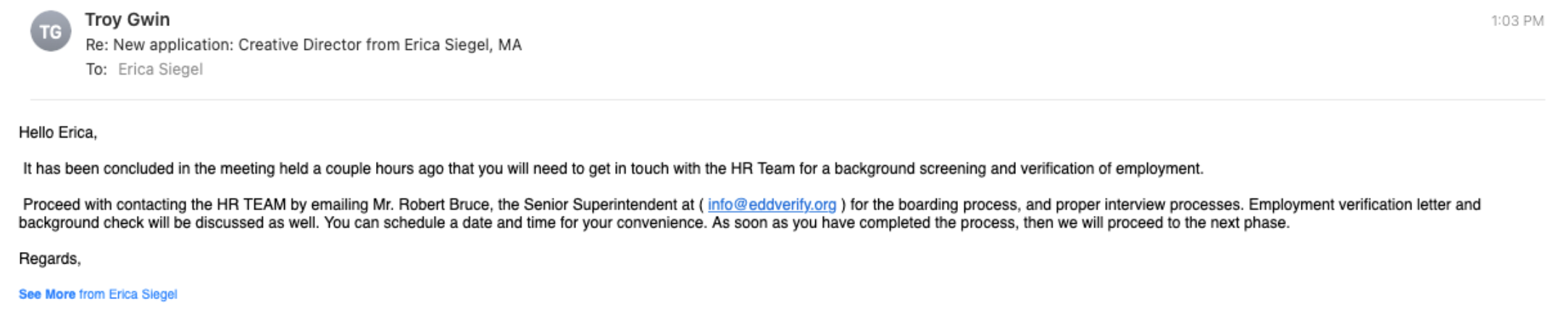

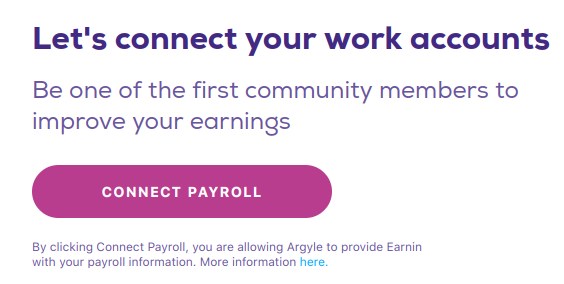

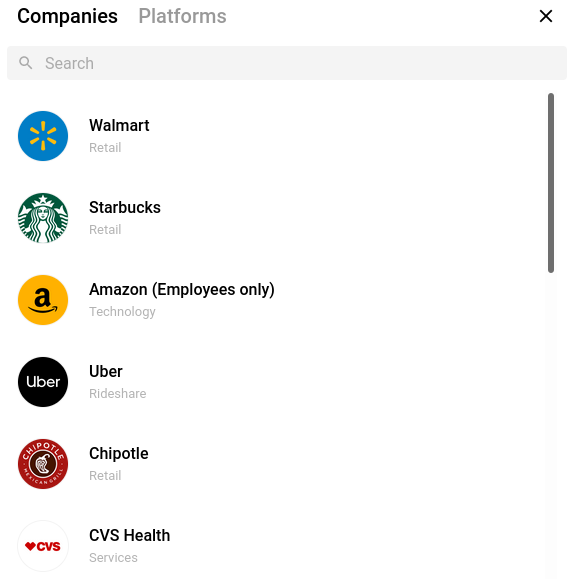

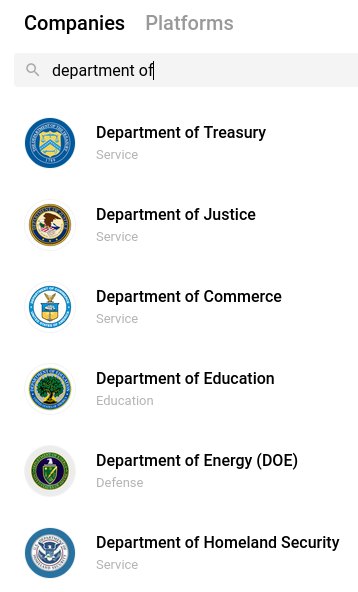

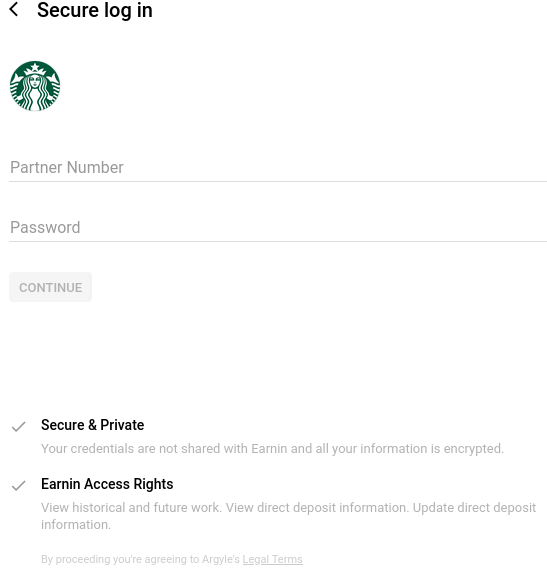

But the recruiter completely ignored Siegel’s follow-up questions, instead sending a reply that urged her to get in touch with a contact in human resources to immediately begin the process of formalizing her employment. Which of course involves handing over one’s personal (driver’s license info) and financial details for direct deposit.

Multiple things about this job offer didn’t smell right to Siegel.

“I usually have six or seven interviews before getting a job,” Siegel said. “Hardly ever in my lifetime have I seen a role that flexible, completely remote and paid the kind of money I would ask for. You never get all three of those things.”

So she called her dad, an environmental attorney who happens to know and have worked with people at the real Geosyntec Consultants. Then she got in touch with the real Troy Gwin, who confirmed her suspicions that the whole thing was a scam.

“Even after the real Troy said they’d gotten these [LinkedIn] ads shut down, this guy was still emailing me asking for my HR information,” Siegel said. “So my dad said, ‘Troll him back, and tell him you want a signing bonus via money order.’ I was like, okay, what’s the worst that could happen? I never heard from him again.” Continue reading