At the height of his cybercriminal career, the hacker known as “Hieupc” was earning $125,000 a month running a bustling identity theft service that siphoned consumer dossiers from some of the world’s top data brokers. That is, until his greed and ambition played straight into an elaborate snare set by the U.S. Secret Service. Now, after more than seven years in prison Hieupc is back in his home country and hoping to convince other would-be cybercrooks to use their computer skills for good.

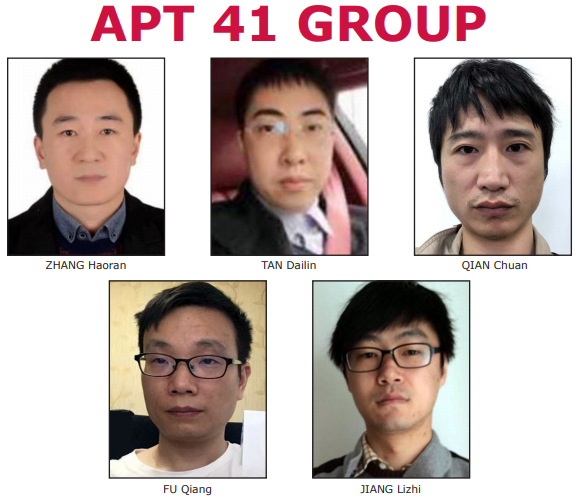

Hieu Minh Ngo, in his teens.

For several years beginning around 2010, a lone teenager in Vietnam named Hieu Minh Ngo ran one of the Internet’s most profitable and popular services for selling “fullz,” stolen identity records that included a consumer’s name, date of birth, Social Security number and email and physical address.

Ngo got his treasure trove of consumer data by hacking and social engineering his way into a string of major data brokers. By the time the Secret Service caught up with him in 2013, he’d made over $3 million selling fullz data to identity thieves and organized crime rings operating throughout the United States.

Matt O’Neill is the Secret Service agent who in February 2013 successfully executed a scheme to lure Ngo out of Vietnam and into Guam, where the young hacker was arrested and sent to the mainland U.S. to face prosecution. O’Neill now heads the agency’s Global Investigative Operations Center, which supports investigations into transnational organized criminal groups.

O’Neill said he opened the investigation into Ngo’s identity theft business after reading about it in a 2011 KrebsOnSecurity story, “How Much is Your Identity Worth?” According to O’Neill, what’s remarkable about Ngo is that to this day his name is virtually unknown among the pantheon of infamous convicted cybercriminals, the majority of whom were busted for trafficking in huge quantities of stolen credit cards.

Ngo’s businesses enabled an entire generation of cybercriminals to commit an estimated $1 billion worth of new account fraud, and to sully the credit histories of countless Americans in the process.

“I don’t know of any other cybercriminal who has caused more material financial harm to more Americans than Ngo,” O’Neill told KrebsOnSecurity. “He was selling the personal information on more than 200 million Americans and allowing anyone to buy it for pennies apiece.”

Freshly released from the U.S. prison system and deported back to Vietnam, Ngo is currently finishing up a mandatory three-week COVID-19 quarantine at a government-run facility. He contacted KrebsOnSecurity from inside this facility with the stated aim of telling his little-known story, and to warn others away from following in his footsteps.

BEGINNINGS

Ten years ago, then 19-year-old hacker Ngo was a regular on the Vietnamese-language computer hacking forums. Ngo says he came from a middle-class family that owned an electronics store, and that his parents bought him a computer when he was around 12 years old. From then on out, he was hooked.

In his late teens, he traveled to New Zealand to study English at a university there. By that time, he was already an administrator of several dark web hacker forums, and between his studies he discovered a vulnerability in the school’s network that exposed payment card data.

“I did contact the IT technician there to fix it, but nobody cared so I hacked the whole system,” Ngo recalled. “Then I used the same vulnerability to hack other websites. I was stealing lots of credit cards.”

Ngo said he decided to use the card data to buy concert and event tickets from Ticketmaster, and then sell the tickets at a New Zealand auction site called TradeMe. The university later learned of the intrusion and Ngo’s role in it, and the Auckland police got involved. Ngo’s travel visa was not renewed after his first semester ended, and in retribution he attacked the university’s site, shutting it down for at least two days.

Ngo said he started taking classes again back in Vietnam, but soon found he was spending most of his time on cybercrime forums.

“I went from hacking for fun to hacking for profits when I saw how easy it was to make money stealing customer databases,” Ngo said. “I was hanging out with some of my friends from the underground forums and we talked about planning a new criminal activity.”

“My friends said doing credit cards and bank information is very dangerous, so I started thinking about selling identities,” Ngo continued. “At first I thought well, it’s just information, maybe it’s not that bad because it’s not related to bank accounts directly. But I was wrong, and the money I started making very fast just blinded me to a lot of things.”

MICROBILT

His first big target was a consumer credit reporting company in New Jersey called MicroBilt.

“I was hacking into their platform and stealing their customer database so I could use their customer logins to access their [consumer] databases,” Ngo said. “I was in their systems for almost a year without them knowing.”

Very soon after gaining access to MicroBilt, Ngo says, he stood up Superget[.]info, a website that advertised the sale of individual consumer records. Ngo said initially his service was quite manual, requiring customers to request specific states or consumers they wanted information on, and he would conduct the lookups by hand.

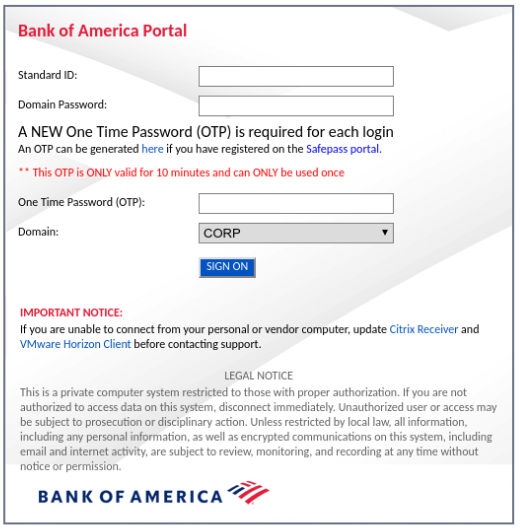

Ngo’s former identity theft service, superget[.]info

“I was trying to get more records at once, but the speed of our Internet in Vietnam then was very slow,” Ngo recalled. “I couldn’t download it because the database was so huge. So I just manually search for whoever need identities.”

But Ngo would soon work out how to use more powerful servers in the United States to automate the collection of larger amounts of consumer data from MicroBilt’s systems, and from other data brokers. As I wrote of Ngo’s service back in November 2011:

“Superget lets users search for specific individuals by name, city, and state. Each “credit” costs USD$1, and a successful hit on a Social Security number or date of birth costs 3 credits each. The more credits you buy, the cheaper the searches are per credit: Six credits cost $4.99; 35 credits cost $20.99, and $100.99 buys you 230 credits. Customers with special needs can avail themselves of the “reseller plan,” which promises 1,500 credits for $500.99, and 3,500 credits for $1000.99.

“Our Databases are updated EVERY DAY,” the site’s owner enthuses. “About 99% nearly 100% US people could be found, more than any sites on the internet now.”

Ngo’s intrusion into MicroBilt eventually was detected, and the company kicked him out of their systems. But he says he got back in using another vulnerability.

“I was hacking them and it was back and forth for months,” Ngo said. “They would discover [my accounts] and fix it, and I would discover a new vulnerability and hack them again.”

COURT (AD)VENTURES, AND EXPERIAN

This game of cat and mouse continued until Ngo found a much more reliable and stable source of consumer data: A U.S. based company called Court Ventures, which aggregated public records from court documents. Ngo wasn’t interested in the data collected by Court Ventures, but rather in its data sharing agreement with a third-party data broker called U.S. Info Search, which had access to far more sensitive consumer records.

Using forged documents and more than a few lies, Ngo was able to convince Court Ventures that he was a private investigator based in the United States.

“At first [when] I sign up they asked for some documents to verify,” Ngo said. “So I just used some skill about social engineering and went through the security check.”

Then, in March 2012, something even more remarkable happened: Court Ventures was purchased by Experian, one of the big three major consumer credit bureaus in the United States. And for nine months after the acquisition, Ngo was able to maintain his access.

“After that, the database was under control by Experian,” he said. “I was paying Experian good money, thousands of dollars a month.”

Whether anyone at Experian ever performed due diligence on the accounts grandfathered in from Court Ventures is unclear. But it wouldn’t have taken a rocket surgeon to figure out that this particular customer was up to something fishy.

For one thing, Ngo paid the monthly invoices for his customers’ data requests using wire transfers from a multitude of banks around the world, but mostly from new accounts at financial institutions in China, Malaysia and Singapore.

O’Neill said Ngo’s identity theft website generated tens of thousands of queries each month. For example, the first invoice Court Ventures sent Ngo in December 2010 was for 60,000 queries. By the time Experian acquired the company, Ngo’s service had attracted more than 1,400 regular customers, and was averaging 160,000 monthly queries.

More importantly, Ngo’s profit margins were enormous.

“His service was quite the racket,” he said. “Court Ventures charged him 14 cents per lookup, but he charged his customers about $1 for each query.”

By this time, O’Neill and his fellow Secret Service agents had served dozens of subpoenas tied to Ngo’s identity theft service, including one that granted them access to the email account he used to communicate with customers and administer his site. The agents discovered several emails from Ngo instructing an accomplice to pay Experian using wire transfers from different Asian banks. Continue reading →