Researchers this week published information about a newfound, serious weakness in WPA2 — the security standard that protects all modern Wi-Fi networks. What follows is a short rundown on what exactly is at stake here, who’s most at-risk from this vulnerability, and what organizations and individuals can do about it.

Short for Wi-Fi Protected Access II, WPA2 is the security protocol used by most wireless networks today. Researchers have discovered and published a flaw in WPA2 that allows anyone to break this security model and steal data flowing between your wireless device and the targeted Wi-Fi network, such as passwords, chat messages and photos.

“The attack works against all modern protected Wi-Fi networks,” the researchers wrote of their exploit dubbed “KRACK,” short for “Key Reinstallation AttaCK.”

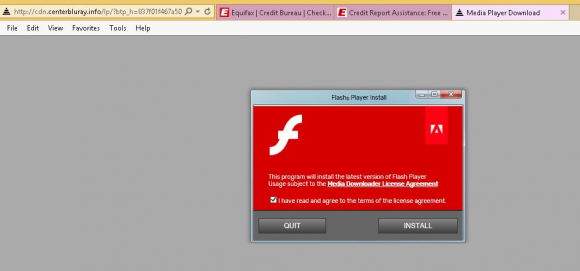

“Depending on the network configuration, it is also possible to inject and manipulate data,” the researchers continued. “For example, an attacker might be able to inject ransomware or other malware into websites. The weaknesses are in the Wi-Fi standard itself, and not in individual products or implementations. Therefore, any correct implementation of WPA2 is likely affected.”

What that means is the vulnerability potentially impacts a wide range of devices including those running operating systems from Android, Apple, Linux, OpenBSD and Windows.

As scary as this attack sounds, there are several mitigating factors at work here. First off, this is not an attack that can be pulled off remotely: An attacker would have to be within range of the wireless signal between your device and a nearby wireless access point.

More importantly, most sensitive communications that might be intercepted these days, such as interactions with your financial institution or browsing email, are likely already protected end-to-end with Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) encryption that is separate from any encryption added by WPA2 — i.e., any connection in your browser that starts with “https://”.

Also, the public announcement about this security weakness was held for weeks in order to give Wi-Fi hardware vendors a chance to produce security updates. The Computer Emergency Readiness Team has a running list of hardware vendors that are known to be affected by this, as well as links to available advisories and patches.

“There is no evidence that the vulnerability has been exploited maliciously, and Wi-Fi Alliance has taken immediate steps to ensure users can continue to count on Wi-Fi to deliver strong security protections,” reads a statement published today by a Wi-Fi industry trade group. “This issue can be resolved through straightforward software updates, and the Wi-Fi industry, including major platform providers, has already started deploying patches to Wi-Fi users. Users can expect all their Wi-Fi devices, whether patched or unpatched, to continue working well together.”

Sounds great, but in practice a great many products on the CERT list are currently designated “unknown” as to whether they are vulnerable to this flaw. I would expect this list to be updated in the coming days and weeks as more information comes in.

Some readers have asked if MAC address filtering will protect against this attack. Every network-capable device has a hard-coded, unique “media access control” or MAC address, and most Wi-Fi routers have a feature that lets you only allow access to your network for specified MAC addresses.

However, because this attack compromises the WPA2 protocol that both your wireless devices and wireless access point use, MAC filtering is not a particularly effective deterrent against this attack. Also, MAC addresses can be spoofed fairly easily.

To my mind, those most at risk from this vulnerability are organizations that have not done a good job separating their wireless networks from their enterprise, wired networks. Continue reading

Hyatt said its cyber security team discovered signs of unauthorized access to payment card information from cards manually entered or swiped at the front desk of certain Hyatt-managed locations between March 18, 2017 and July 2, 2017.

Hyatt said its cyber security team discovered signs of unauthorized access to payment card information from cards manually entered or swiped at the front desk of certain Hyatt-managed locations between March 18, 2017 and July 2, 2017. Roughly half of the flaws Microsoft addressed this week are in the code that makes up various versions of Windows, and 28 of them were labeled “critical” — meaning malware or malicious attackers could use the weaknesses to break into Windows computers remotely with no help from users.

Roughly half of the flaws Microsoft addressed this week are in the code that makes up various versions of Windows, and 28 of them were labeled “critical” — meaning malware or malicious attackers could use the weaknesses to break into Windows computers remotely with no help from users. Previously, Equifax said the breach impacted approximately 400,000 U.K. residents. But in a statement released Tuesday, Equifax said it would notify 693,665 U.K. consumers by mail that their personal information was jeopardized in the breach. This includes:

Previously, Equifax said the breach impacted approximately 400,000 U.K. residents. But in a statement released Tuesday, Equifax said it would notify 693,665 U.K. consumers by mail that their personal information was jeopardized in the breach. This includes: