Most organizations only grow in security maturity the hard way — that is, from the intense learning that takes place in the wake of a costly data breach. That may be because so few company leaders really grasp the centrality of computer and network security to the organization’s overall goals and productivity, and fewer still have taken an honest inventory of what may be at stake in the event that these assets are compromised.

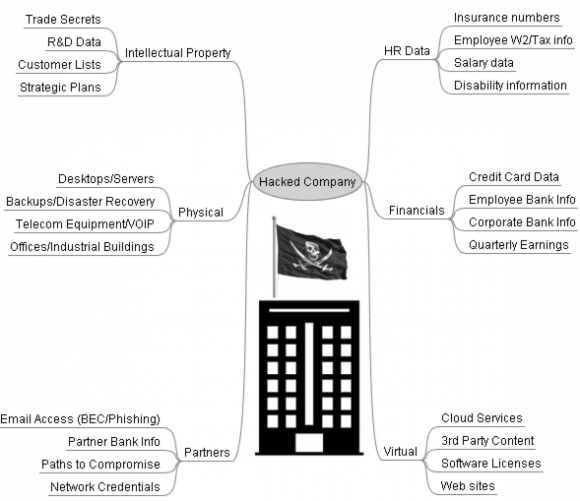

If you’re unsure how much of your organization’s strategic assets may be intimately tied up with all this technology stuff, ask yourself what would be of special worth to a network intruder. Here’s a look at some of the key corporate assets that may be of interest and value to modern bad guys.

This isn’t meant to be an exhaustive list; I’m sure we can all think of other examples, and perhaps if I receive enough suggestions from readers I’ll update this graphic. But the point is that whatever paltry monetary value the cybercrime underground may assign to these stolen assets individually, they’re each likely worth far more to the victimized company — if indeed a price can be placed on them at all.

In years past, most traditional, financially-oriented cybercrime was opportunistic: That is, the bad guys tended to focus on getting in quickly, grabbing all the data that they knew how to easily monetize, and then perhaps leaving behind malware on the hacked systems that abused them for spam distribution.

These days, an opportunistic, mass-mailed malware infection can quickly and easily morph into a much more serious and sustained problem for the victim organization (just ask Target). This is partly because many of the criminals who run large spam crime machines responsible for pumping out the latest malware threats have grown more adept at mining and harvesting stolen data.

That data mining process involves harvesting and stealthily testing interesting and potentially useful usernames and passwords stolen from victim systems. Today’s more clueful cybercrooks understand that if they can identify compromised systems inside organizations that may be sought-after targets of organized cybercrime groups, those groups might be willing to pay handsomely for such ready-made access.

It’s also never been easier for disgruntled employees to sell access to their employer’s systems or data, thanks to the proliferation of open and anonymous cybercrime forums on the Dark Web that serve as a bustling marketplace for such commerce. In addition, the past few years have seen the emergence of several very secretive crime forums wherein members routinely solicited bids regarding names of people at targeted corporations that could serve as insiders, as well as lists of people who might be susceptible to being recruited or extorted.

The sad truth is that far too many organizations spend only what they have to on security, which is often to meet some kind of compliance obligation such as HIPAA to protect healthcare records, or PCI certification to be able to handle credit card data, for example. However, real and effective security is about going beyond compliance — by focusing on rapidly detecting and responding to intrusions, and constantly doing that gap analysis to identify and shore up your organization’s weak spots before the bad guys can exploit them.

Those weak spots very well may be your users, by the way. A number of security professionals I know and respect claim that security awareness training for employees doesn’t move the needle much. These naysayers note that there will always be employees who will click on suspicious links and open email attachments no matter how much training they receive. While this is generally true, at least such security training and evaluation offers the employer a better sense of which employees may need more heavy monitoring on the job and perhaps even additional computer and network restrictions.

If you help run an organization, consider whether the leadership is investing enough to secure everything that’s riding on top of all that technology powering your mission: Chances are there’s a great deal more at stake than you realize.

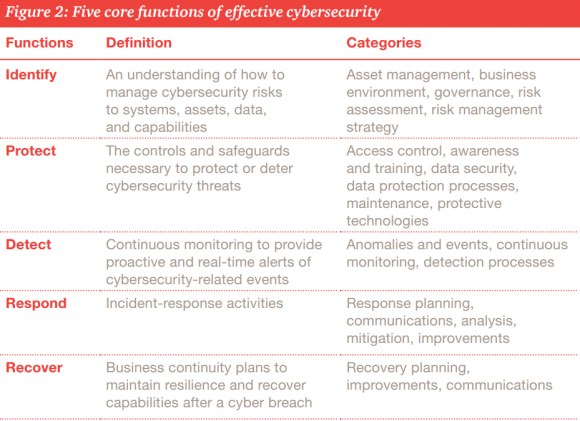

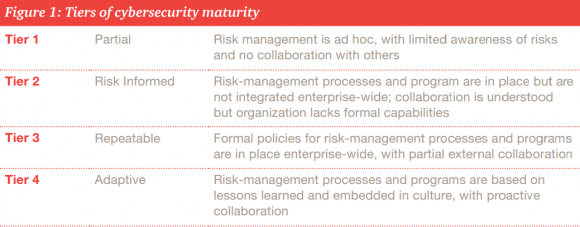

Organizational leaders in search of a clue about how to increase both their security maturity and the resiliency of all their precious technology stuff could do far worse than to start with the Cybersecurity Framework developed by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST), the federal agency that works with industry to develop and apply technology, measurements, and standards. This primer (PDF) from PWC does a good job of explaining why the NIST Framework may be worth a closer look.

If you liked this post, you may enjoy the other two posts in this series — The Scrap Value of a Hacked PC and The Value of a Hacked Email Account.

Great article, Brian. Very useful if the CEOs read it. In my speed reading, I did not see any mention of the cost of the lack of customer confidence after word of a breach gets out. And then there are possible legal costs as well.

Regards,

Unfortunately, it seems the general consumer has a short-term memory of breach events. While the most publicized have some short to intermediate term influence on purchasing decisions (TJMaxx, Target, Home Depot), the effect soon wears off. Convenience, price, and product choices appear to trump a lack of confidence, if sales numbers are anything to go by.

You’re putting the onus in entirely the wrong place. If I know that Target had been hacked … just why should that influence my decision to shop there? The worst that can happen is that my credit card number is stolen. But I’m shielded from any liability. The charges will be reversed and I’ll be given a new number. Maybe I have a few days of inconvenience before I receive the new card.

The system deliberately isolates consumers from the consequences of bad security by the other players in the system. And, in fact, that’s as it should be: The consumer is in the *weakest* position to prevent, or even detect, frauds. Sure, the consumer shouldn’t leave his card lying around (but he should feel free, in the US, to hand it to a minimum-wage employee at a random coffee shop). But in fact physical theft or copying of cards by a human being is a pretty trivial component of CC fraud today. The only thing the consumer really should be doing – and the only thing the system rewards him for doing – is to check his bills and report any issues on a timely basis.

So, yes, I as a consumer will choose where I shop based on price, convenience, and similar factors. If you as seller (who eats almost all the cost of fraud) or as bank or as any of the intermediaries (who do have to pay to run various security elements in the process) are concerned about security costs … do what needs to be done to make the system secure.

We repeatedly see posting here from people who say “I avoid the security problems by using cash”. They’re avoiding *nothing*. To the contrary. When my wallet is stolen, I can get my credit cards replaced within a few days; no real harm done. The cash in their wallet is gone for good.

— Jerry

Two areas that are perhaps implied but might deserve more attention are the prevention of risk and the transfer of risk (insurance or the like). This is actually a nice introduction to cybersecurity risk and is perhaps worded so as to be useful to non-security people, like boards of directors.

Yes! always a good way to communicate the cost of risk. And also a nice mitigation against the probable risk that can’t easily identified. Once the additional liability is shown in $$$ it gets the attention it needs at the appropriate level of management.

Only item I am seeing that is missing is the the desire to cause outages, panic, or other impact to the productivity or availability of a particular service a company provides. Possibly even used to unravel the confidence in a particular entity (e.g. DNC Attack). Other examples would include attacks on Ukraine’s power infrastructure, attacks on process control equipment in a manufacturing facility, ransomware on lots of machines preventing access to them (e.g. hospitals or manufacturing), etc. Great article!

I always enjoy your articles. I agree with what you say about organizations often doing the minimum required in order to meet compliance. I saw a great quote a couple of years ago from Bob Russo, PCI Security Standards Council – “Compliance is asking you to put a lock on the door. Security is making sure you lock it every day.” Too many organizations look at compliance as a checklist that you check off once a year, rather than looking at both compliance and security as something that needs to be continuous. By the way, in your article you refer to HIPPA – but the correct acronym is HIPAA.

My comment concerns definitions. Security “is the state of being free from danger or threat” and cybersecurity is the state of being protected against the criminal or unauthorized use of electronic data. Perhaps the definition of cybersecurity is too narrow if you are trying to sell the concept to a business. If cybersecurity included other aspects of protecting data from of from dangers, such as natural disasters, fires as well as hackers, perhaps the concept maybe more palatable to businesses.

Great article! For security to be effective you have to be able to measure the security risk to manage it. To date no security company offers this perspective. Security and Enterprise Risk Management will be harmonized, integrated to solve the complexities of Cybersecurity. Communication between the two professions is the first step. Security professional have no understanding of the regulatory requirements for managing net profits, an organizations viability, from a operational risk, quantification of Cyber Risk or creation of a Cyber Risk Transfer Pricing Mechanism or Cyber Risk Capital Management perspective. Chief Risk officers and Boards have little to no understanding of what a CSO or CISO does or their daily functions and responsibilities. The Digital Risk Manager is just starting to be considered in the overall organizational structure. Once the full extent of the embedded options driving an organizations unique attack surface are understood, the extent of the infrastructure enhancements will be obvious. It is not possible to conduct business in most industries with the prevalence of so many capable, diverse, foes. We can’t measure the risk, therefore we can’t manage the risk. We can’t price Cyber Insurance because the industry isn’t measuring the right variables. Each company is responsible for their own net profit management, viability. For every company, the answer lies within, understanding the infrastructure, your Cyber data and intelligence and the quantification of your Cyber Risk. This path, this risk methodology, has been repeated numerous times in the history of Risk Management and will be the key to solving the complexities of Cyber Risk Management. Soon, your Corporate Ratings, your Cyber Risk Management, your Cyber Risk Capital Management will all be linked together and the extensive, destructive, era of Cyber War will subside.

IAPP is an organization that does bring these two groups together in an effective and meaningful way. Nice resource for Security guys, Risk management and Legal teams.

Quarterly earnings. Yes. Exceptionally valuable if obtained before official release.

http://bloom.bg/1P31VLI

I enjoyed reading your article. In my professional life I use the NIST framework for a lot of my clients. It forms a solid basis for selecting those controls that are relevant for you at the different framework categories.

What I’ve seen at many organizations that the number of security controls they have in the detect and response categories are limit. Many (traditional) organizations have loads and loads of preventive and detective controls. It’s (in my view) incorrect to assume that you can always keep the bad guys out. Instead, you should assume that you will eventually be breached. The question is when, how quickly you’re able to detect it, how much it will hurt you and how you respond to it.

We do a lot of awareness (tabletop) exercises in which we perform different scenario’s of cyber events. The audience is often the c-suite, executive board or business unit managers. In these exercises we let them think of the impact of the cyber event on their business. This helps then understand that a cyber event (or attack) is not just a technical issue, it’s in fact more a business issue.

I don’t agree necessarily agree on the definition ‘cybersecurity maturity’ in the picture from PWC. If you read the NIST cybersecurity framework, the actual definition is different.

Again, good post and definitely something that one should think about in the context of their organization!

Meanwhile…..

Every computer on the network continues to run Java (to allow web-based access/use of outside resources that really need to be brought back in-house) and Flash (for training videos).

The suites will just delegate commands/policies downward to someone that likely does not have an actual desire to keep the network integrity maintained. At the end of the day it will all be outsourced to a separate company.

That’s IF anything happens at all.

Corporate email account turned spambot is da devil Bobby Boucher.

Businesses routinely monetize a rather amorphous asset called “good will.” How much of a hit that item takes on the balance sheet of a severely hacked corporation is hard to estimate, but worth some consideration in an iteration of assets.

And, as always, we assume it’s a ” bad guy” wanting your data. It’s also your competition in the business world. Wanting to look at your sales leads, your services offered, and how much you charge for whatever you do. Too little is expressed, as, protection of product leads. And how you get them.

Sometimes firms in the same sector will actually allow each other to do this so that they have plausible deniability against charges of collusion.

In addition to PWC, the NIST National Cybersecurity Center of Excellence (NCCoE) is driving cybersecurity adoption efforts across the critical infrastructure sectors. (Full disclaimer: I am an engineer at the NCCoE.) The NCCoE is helping the Coast Guard develop a CSF profile for the bulk liquid transport sub-sector of the oil and gas industry. The New York Power Authority (energy sector) recently indicated it intends to implement the NCCoE identity and access management practice guide NIST SP 1800-2 to improve their cybersecurity posture. The NCCoE isn’t regulatory but takes into account rules, regulations, best practices or requirements within industry to develop customized reference designs to solve technical cybersecurity concerns. The focus is on collaboration with industry and technology vendors to come up with relevant and practical example solutions, and we’re always looking for people interested in guiding and developing reference designs focused on solutions rather than just vulnerabilities and challenges. If you’re interested in providing feedback or guidance, check us out at https://nccoe.nist.gov.

Great article, Brian. On the intellectual part of the diagram, software is missing (arguably covered in R&D data but maybe you want to call it out specifically). For a hi-tech company the software source code is often “the” IP.

Regards,

BlueCat Networks

All too true!

Where does some one fit in an organization chart who is responsible for cybersecurity? Are they the director of the cybersecurity department or are they a member of another department?

Executives are very aware. Perhaps, executives have a sense of futility that whatever they do, they will be breached. Isn’t that what they are being told…worse, that they likely have already been breached? Experts, professionals, professional organizations, industries, and government pile up a mountain of warnings, regulations, standards, and guidelines. Sorting all of these out with regard to their relevance to any organization is daunting. The cost is unacceptable. We need fewer “purists” and more pragmatists, both those promoting security standards, and those delivering security services. The CSC Top Twenty and OWASP Top 10 are good starts, but still represent a lot of cost, effort, and time. Can we get focused on say five or so things that are the best things to do on a budget.

You mentioned the CSC Top 20. If I’m not mistaken, it identifies a “First Five”. Why not start there?

Good idea. I wonder whether consensus could be achieved across al stakeholders?

in email scamming user education is not enough as it has been proven by the industry

we introduce a pure technological fool-proof solution against BEC,CEO scam attempts and overall advanced targeted email attacks that will solve this once and for all

One thing you might have missed is private keys for digital signatures. If a private key for code signing is stolen, the thieves can use it to sign malware. This allows trojans to appear more authentic. Revoking the certificate and issuing a new one can be a big pain, especially if the company distributes software on disk.

A similar issue exists for SSL private keys, where an attacker can use it to impersonate the company’s web site(s) through an MITM.

Sometimes an exploit doesn’t directly target the hacked company. For instance, if a network device vendor is hacked, rather than stealing employee information, or credit cards, a hacker might try to identify hidden vulnerabilities in their system in an effort to attack customers of that network appliance.

Sometimes they don’t even have to look directly at the source code. For example, there was a bug in the Bugzilla issue tracker that allowed anyone to create a user that could see hidden issues, including unfixed security vulnerabilities not known publicly. Since Bugzilla is used by Mozilla, the organization that maintains Firefox, this Bugzilla vulnerability was a big deal.

Getting access to private communications about unfixed security vulnerabilities can be a goldmine for an attacker. The hard work is already done for them.

Good comments!

In response to asking for a shorter list, recommend a look at the enterprise to-do list on the NSA website entitled the “NSA Methodology for Adversary Obstruction” It was the practical outcome of a lively debate between hunters and defenders.

One of the key authors commented that, if all CEOs did was to ensure the top 3 or 4, that would close off a large portion of the risk vectors.

Brian asked ” Can we get focused on say five or so things that are the best things to do on a budget.”

What is your list? Since I am just one person looking at a pc screen, my list is very simple. I have no idea what to do if I owned a small business. I worked for a large company in the late 80s and to the best of my knowledge cybersecurity was not an issue.