John Gilmore, an American entrepreneur and civil libertarian, once famously quipped that “the Internet interprets censorship as damage and routes around it.” This notion undoubtedly rings true for those who see national governments as the principal threats to free speech.

However, events of the past week have convinced me that one of the fastest-growing censorship threats on the Internet today comes not from nation-states, but from super-empowered individuals who have been quietly building extremely potent cyber weapons with transnational reach.

More than 20 years after Gilmore first coined that turn of phrase, his most notable quotable has effectively been inverted — “Censorship can in fact route around the Internet.” The Internet can’t route around censorship when the censorship is all-pervasive and armed with, for all practical purposes, near-infinite reach and capacity. I call this rather unwelcome and hostile development the “The Democratization of Censorship.”

Allow me to explain how I arrived at this unsettling conclusion. As many of you know, my site was taken offline for the better part of this week. The outage came in the wake of a historically large distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attack which hurled so much junk traffic at Krebsonsecurity.com that my DDoS protection provider Akamai chose to unmoor my site from its protective harbor.

Let me be clear: I do not fault Akamai for their decision. I was a pro bono customer from the start, and Akamai and its sister company Prolexic have stood by me through countless attacks over the past four years. It just so happened that this last siege was nearly twice the size of the next-largest attack they had ever seen before. Once it became evident that the assault was beginning to cause problems for the company’s paying customers, they explained that the choice to let my site go was a business decision, pure and simple.

Nevertheless, Akamai rather abruptly informed me I had until 6 p.m. that very same day — roughly two hours later — to make arrangements for migrating off their network. My main concern at the time was making sure my hosting provider wasn’t going to bear the brunt of the attack when the shields fell. To ensure that absolutely would not happen, I asked Akamai to redirect my site to 127.0.0.1 — effectively relegating all traffic destined for KrebsOnSecurity.com into a giant black hole.

Today, I am happy to report that the site is back up — this time under Project Shield, a free program run by Google to help protect journalists from online censorship. And make no mistake, DDoS attacks — particularly those the size of the assault that hit my site this week — are uniquely effective weapons for stomping on free speech, for reasons I’ll explore in this post.

Google’s Project Shield is now protecting KrebsOnSecurity.com

Why do I speak of DDoS attacks as a form of censorship? Quite simply because the economics of mitigating large-scale DDoS attacks do not bode well for protecting the individual user, to say nothing of independent journalists.

In an interview with The Boston Globe, Akamai executives said the attack — if sustained — likely would have cost the company millions of dollars. In the hours and days following my site going offline, I spoke with multiple DDoS mitigation firms. One offered to host KrebsOnSecurity for two weeks at no charge, but after that they said the same kind of protection I had under Akamai would cost between $150,000 and $200,000 per year.

Ask yourself how many independent journalists could possibly afford that kind of protection money? A number of other providers offered to help, but it was clear that they did not have the muscle to be able to withstand such massive attacks.

I’ve been toying with the idea of forming a 501(c)3 non-profit organization — ‘The Center for the Defense of Internet Journalism’, if you will — to assist Internet journalists with obtaining the kind of protection they may need when they become the targets of attacks like the one that hit my site. Maybe a Kickstarter campaign, along with donations from well-known charitable organizations, could get the ball rolling. It’s food for thought.

CALIBRATING THE CANNONS

Earlier this month, noted cryptologist and security blogger Bruce Schneier penned an unusually alarmist column titled, “Someone Is Learning How to Take Down the Internet.” Citing unnamed sources, Schneier warned that there was strong evidence indicating that nation-state actors were actively and aggressively probing the Internet for weak spots that could allow them to bring the entire Web to a virtual standstill.

“Someone is extensively testing the core defensive capabilities of the companies that provide critical Internet services,” Schneier wrote. “Who would do this? It doesn’t seem like something an activist, criminal, or researcher would do. Profiling core infrastructure is common practice in espionage and intelligence gathering. It’s not normal for companies to do that.”

Schneier continued:

“Furthermore, the size and scale of these probes — and especially their persistence — points to state actors. It feels like a nation’s military cyber command trying to calibrate its weaponry in the case of cyberwar. It reminds me of the US’s Cold War program of flying high-altitude planes over the Soviet Union to force their air-defense systems to turn on, to map their capabilities.”

Whether Schneier’s sources were accurate in their assessment of the actors referenced in his blog post is unknown. But as my friend and mentor Roland Dobbins at Arbor Networks eloquently put it, “When it comes to DDoS attacks, nation-states are just another player.”

“Today’s reality is that DDoS attacks have become the Great Equalizer between private actors & nation-states,” Dobbins quipped.

UM…YOUR RERUNS OF ‘SEINFELD’ JUST ATTACKED ME

What exactly was it that generated the record-smashing DDoS of 620 Gbps against my site this week? Was it a space-based weapon of mass disruption built and tested by a rogue nation-state, or an arch villain like SPECTRE from the James Bond series of novels and films? If only the enemy here was that black-and-white.

No, as I reported in the last blog post before my site was unplugged, the enemy in this case was far less sexy. There is every indication that this attack was launched with the help of a botnet that has enslaved a large number of hacked so-called “Internet of Things,” (IoT) devices — mainly routers, IP cameras and digital video recorders (DVRs) that are exposed to the Internet and protected with weak or hard-coded passwords. Most of these devices are available for sale on retail store shelves for less than $100, or — in the case of routers — are shipped by ISPs to their customers.

Some readers on Twitter have asked why the attackers would have “burned” so many compromised systems with such an overwhelming force against my little site. After all, they reasoned, the attackers showed their hand in this assault, exposing the Internet addresses of a huge number of compromised devices that might otherwise be used for actual money-making cybercriminal activities, such as hosting malware or relaying spam. Surely, network providers would take that list of hacked devices and begin blocking them from launching attacks going forward, the thinking goes.

As KrebsOnSecurity reader Rob Wright commented on Twitter, “the DDoS attack on @briankrebs feels like testing the Death Star on the Millennium Falcon instead of Alderaan.” I replied that this maybe wasn’t the most apt analogy. The reality is that there are currently millions — if not tens of millions — of insecure or poorly secured IoT devices that are ripe for being enlisted in these attacks at any given time. And we’re adding millions more each year.

I suggested to Mr. Wright perhaps a better comparison was that ne’er-do-wells now have a virtually limitless supply of Stormtrooper clones that can be conscripted into an attack at a moment’s notice.

A scene from the 1977 movie Star Wars, in which the Death Star tests its firepower by blowing up a planet.

SHAMING THE SPOOFERS

The problem of DDoS conscripts goes well beyond the millions of IoT devices that are shipped insecure by default: Countless hosting providers and ISPs do nothing to prevent devices on their networks from being used by miscreants to “spoof” the source of DDoS attacks.

As I noted in a November 2015 story, The Lingering Mess from Default Insecurity, one basic step that many ISPs can but are not taking to blunt these attacks involves a network security standard that was developed and released more than a dozen years ago. Known as BCP38, its use prevents insecure resources on an ISPs network (hacked servers, computers, routers, DVRs, etc.) from being leveraged in such powerful denial-of-service attacks.

Using a technique called traffic amplification and reflection, the attacker can reflect his traffic from one or more third-party machines toward the intended target. In this type of assault, the attacker sends a message to a third party, while spoofing the Internet address of the victim. When the third party replies to the message, the reply is sent to the victim — and the reply is much larger than the original message, thereby amplifying the size of the attack.

BCP38 is designed to filter such spoofed traffic, so that it never even traverses the network of an ISP that’s adopted the anti-spoofing measures. However, there are non-trivial economic reasons that many ISPs fail to adopt this best practice. This blog post from the Internet Society does a good job of explaining why many ISPs ultimately decide not to implement BCP38.

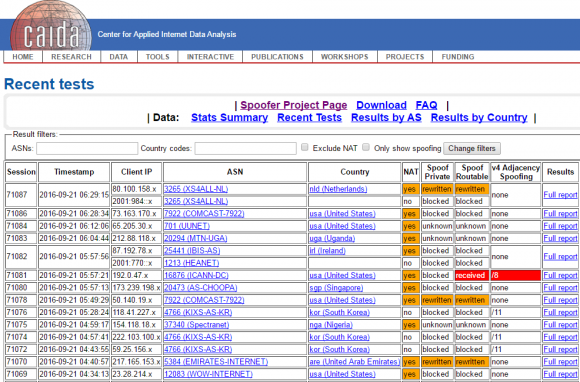

Fortunately, there are efforts afoot to gather information about which networks and ISPs have neglected to filter out spoofed traffic leaving their networks. The idea is that by “naming and shaming” the providers who aren’t doing said filtering, the Internet community might pressure some of these actors into doing the right thing (or perhaps even offer preferential treatment to those providers who do conduct this basic network hygiene).

A research experiment by the Center for Applied Internet Data Analysis (CAIDA) called the “Spoofer Project” is slowly collecting this data, but it relies on users voluntarily running CAIDA’s software client to gather that intel. Unfortunately, a huge percentage of the networks that allow spoofing are hosting providers that offer extremely low-cost, virtual private servers (VPS). And these companies will never voluntarily run CAIDA’s spoof-testing tools.

CAIDA’s Spoofer Project page.

As a result, the biggest offenders will continue to fly under the radar of public attention unless and until more pressure is applied by hardware and software makers, as well as ISPs that are doing the right thing.

How might we gain a more complete picture of which network providers aren’t blocking spoofed traffic — without relying solely on voluntary reporting? That would likely require a concerted effort by a coalition of major hardware makers, operating system manufacturers and cloud providers, including Amazon, Apple, Google, Microsoft and entities which maintain the major Web server products (Apache, Nginx, e.g.), as well as the major Linux and Unix operating systems.

The coalition could decide that they will unilaterally build such instrumentation into their products. At that point, it would become difficult for hosting providers or their myriad resellers to hide the fact that they’re allowing systems on their networks to be leveraged in large-scale DDoS attacks.

To address the threat from the mass-proliferation of hardware devices such as Internet routers, DVRs and IP cameras that ship with default-insecure settings, we probably need an industry security association, with published standards that all members adhere to and are audited against periodically.

The wholesalers and retailers of these devices might then be encouraged to shift their focus toward buying and promoting connected devices which have this industry security association seal of approval. Consumers also would need to be educated to look for that seal of approval. Something like Underwriters Laboratories (UL), but for the Internet, perhaps.

THE BLEAK VS. THE BRIGHT FUTURE

As much as I believe such efforts could help dramatically limit the firepower available to today’s attackers, I’m not holding my breath that such a coalition will materialize anytime soon. But it’s probably worth mentioning that there are several precedents for this type of cross-industry collaboration to fight global cyber threats.

In 2008, the United States Computer Emergency Readiness Team (CERT) announced that researcher Dan Kaminsky had discovered a fundamental flaw in DNS that could allow anyone to intercept and manipulate most Internet-based communications, including email and e-commerce applications. A diverse community of software and hardware makers came together to fix the vulnerability and to coordinate the disclosure and patching of the design flaw.

In 2009, Microsoft heralded the formation of an industry group to collaboratively counter Conficker, a malware threat that infected tens of millions of Windows PCs and held the threat of allowing cybercriminals to amass a stupendous army of botted systems virtually overnight. A group of software and security firms, dubbed the Conficker Cabal, hashed out and executed a plan for corralling infected systems and halting the spread of Conficker.

In 2009, Microsoft heralded the formation of an industry group to collaboratively counter Conficker, a malware threat that infected tens of millions of Windows PCs and held the threat of allowing cybercriminals to amass a stupendous army of botted systems virtually overnight. A group of software and security firms, dubbed the Conficker Cabal, hashed out and executed a plan for corralling infected systems and halting the spread of Conficker.

In 2011, a diverse group of industry players and law enforcement organizations came together to eradicate the threat from the DNS Changer Trojan, a malware strain that infected millions of Microsoft Windows systems and enslaved them in a botnet that was used for large-scale cyber fraud schemes.

These examples provide useful templates for a solution to the DDoS problem going forward. What appears to be missing is any sense of urgency to address the DDoS threat on a coordinated, global scale.

That’s probably because at least for now, the criminals at the helm of these huge DDoS crime machines are content to use them to launch petty yet costly attacks against targets that suit their interests or whims.

For example, the massive 620 Gbps attack that hit my site this week was an apparent retaliation for a story I wrote exposing two Israeli men who were arrested shortly after that story ran for allegedly operating vDOS — until recently the most popular DDoS-for-hire network. The traffic hurled at my site in that massive attack included the text string “freeapplej4ck,” a reference to the hacker nickname used by one of vDOS’s alleged co-founders.

Most of the time, ne’er-do-wells like Applej4ck and others are content to use their huge DDoS armies to attack gaming sites and services. But the crooks maintaining these large crime machines haven’t just been targeting gaming sites. OVH, a major Web hosting provider based in France, said in a post on Twitter this week that it was recently the victim of an even more massive attack than hit my site. According to a Tweet from OVH founder Octave Klaba, that attack was launched by a botnet consisting of more than 145,000 compromised IP cameras and DVRs.

I don’t know what it will take to wake the larger Internet community out of its slumber to address this growing threat to free speech and ecommerce. My guess is it will take an attack that endangers human lives, shuts down critical national infrastructure systems, or disrupts national elections.

But what we’re allowing by our inaction is for individual actors to build the instrumentality of tyranny. And to be clear, these weapons can be wielded by anyone — with any motivation — who’s willing to expend a modicum of time and effort to learn the most basic principles of its operation.

The sad truth these days is that it’s a lot easier to censor the digital media on the Internet than it is to censor printed books and newspapers in the physical world. On the Internet, anyone with an axe to grind and the willingness to learn a bit about the technology can become an instant, self-appointed global censor.

I sincerely hope we can address this problem before it’s too late. And I’m deeply grateful for the overwhelming outpouring of support and solidarity that I’ve seen and heard from so many readers over the past few days. Thank you.

Glad to see you back again. I figure that you are probably stepping on some big toes right now – I am hoping that you can get to the bottom of it. This could be the subject of your next book :-).

Here’s an analogy that leaves me somewhat hopeless, even though I laud Brian for his work in trying to wake the industry up. Yes, the industry, not any one government. The analogy: in telephony, I get many spoofed spam calls every week. The telephone industry response? “Our job is to complete calls no matter how phony or irritating or potentially harmful they may be.” It appears to me that this is the exact same response of ISPs. They know the traffic originating on their networks is illicit, but do nothing.

The difference here is that the junk traffic is designed to prevent your server from working.

Let’s go back to telephony. If the level of junk calls reached such a level that you simply couldn’t make an outgoing call, it would be far more than a nuisance.

But at the end of the day you are right. The providers are clinging to this quaint notion that their job is to deliver every packet, but to change this, one would need better heuristics to figure out what is junk and what isn’t. And the people who are in the business of sending junk content would try and change their own algorithms to get around this. That isn’t too different from what we have now – it is only hosting companies like Akamai that are trying to figure out how to block the content.

There’s no easy answer here. Keep in mind that there’s a whole debate about net neutrality also going on whereupon the providers want to be able to exercise the ability to control traffic flows. To help spur innovation and give consumers freedom of choice, we want ISPs to exercise net neutrality. But we also want ISPs to protect us from attack, and in order to do that, we need to give ISPs the ability to block certain types of traffic that may cause harm. Unfortunately, we have different definitions of what might constitute harm.

Mid and long term, there are several options that we have to resolve the problem of DDoS attacks.

When it comes to filtering traffic, we’d want broader adoption and rollout of mechanisms such as BGP Flowspec that enables us to tell upstream ISPs what traffic we are willing (or not willing) to receive.

When it come to hosting sites, we need to fight distributed attacks with distributed services. Akamai, and CDNs in general, represent one form of distributed services, but longer term, I hope that something like IPFS (https://ipfs.io) might eventually become a viable option for DDoS-resilient hosting.

I assume telephone service providers also make money off the spoofed spam calls (somebody is paying for them).

Glad to see you back. Am a long time reader, first time commenter, who greatly appreciates your expertise. I agree with your conclusion, unfortunately. Sadly, humans insist on learning the hard way. We tend to wait until someone dies before we take a threat seriously. And as you say, by then, the enemy is very strong and prepared. I hope your suffering will be an abject lesson to others out there who won’t wait until it’s too late. Just more proof to me that keeping paper money, books and news media is not old-fashioned, it’s vitally smart.

I’m a long time reader, since the Washington Post days, and all that …

I’m happy to see Project Shield has resolved the issue, at least for now. With the IoT growing at the pace it is, things have the potential to become worse. As others have said, the right thing there is for the device manufacturers to get a clue, step up, and do their part. I’m not sure we want laws and governmental regulations there though. The jury in my head is still out on that one.

Brian, if you do find yourself needing paid DDoS protection at some point, I’m in for $100 a year in a heartbeat. I’m not sure of readership numbers but I suspect they’re rather large. We might could cover a significant part of the cost just among ourselves.

Welcome back!

If you do start a kickstarter campaign or similar, I will donate too. First time reader here. Your work needs to be supported; I’m in.

It seems that the DOS protection business has failed.

If the statement by Akamai can be taken at face value and it really would have cost millions to defend Brian, then they don’t have anything to offer. It does not make sense to pay thousands of dollars per year for insurance, and have it become unaffordable once the protection is actually needed.

Krebs on Security is worthy of Project Shield support. But for those of us who don’t qualify, right now attack beats defense 🙁

Props to Akamai and now Google for materially defending a free press.

While your site was down I bought a copy of “Spam Nation” as a symbolic gesture.

Brian, glad to know your DDoS problem is solved for now. Your work is providing an important public service.

As a homeowner (and the person my family turns to when there’s a problem with the IT stuff in my house), what steps can I take to make sure my devices are not compromised by a botnet?

I have changed the user name and password for the router/gateway provided by my ISP, and I run antivirus software on all my PCs and MacBooks. I use 2-factor authentication where I can.

Any advise would be appreciated.

Thanks.

Keep firmware updated also, on everything. Don’t use hidden SSID. If possible you can change default port so you know if traffic comes into the default it’s not legitimate.

Please explain why one should not use a hidden SSID.

This is “security through obscurity” and while it may make you feel better it does not really make your network any more secure.

The only benefit is that your SSID will not be broadcast as often.

If the SSID is hidden, sending a probe request with NULL as the SSID may cause the AP to reply with a beacon containing the SSID.

Also, as soon as a valid device needs to connect, the SSID will end up being broadcast by the AP.

Further, an attacker may see this as being a sensitive network and spend more time targeting it.

And so on.

Most simple and immediate thing you can do right now, is to ensure that every device on your network.. hardwired or using wireless, have had their default from factory passwords changed.

That will go a long ways towards preventing them from being compromised and used in these kinds of attacks.

Then make sure everything is patched up to current firmware/software revisions where able.

Then accept the fact that you will never be able to secure any computer or device 100%

🙁

I read about this a couple days ago and was surprised they gave up on protection like that. With as much research and independent investigation as you do for the field, seems like industry would back you more than they do.

Why would they?

Because for anything related to spam, ATM fraud, or malware he is usually the only journalist to dig deep and find the facts. He gets referenced by dozens of news corporations on a weekly-monthly basis. In many cases he tried to contact the companies and prevent the PR disaster and damage months before they made the front page.

I had a thought here that maybe some network engineers could think about. Or maybe they have, and there is a good reason why it won’t help.

There is nothing to stop a hosting provider from setting up two subnets. One would be a “public” subnet – very much like what they have now. The other would be “internal” – intended to support DNS, NTP and other sorts of administrative requests, but nothing else (essentially all of the valid UDP traffic would go on this subnet).

The hosting provider can then configure their hosts to have more than one network connector. One would connect to the public subnet, the other would connect to the internal subnet. The internal subnet would ultimately need to route the UDP traffic to the rest of the internet, but that routing could take paths that are completely different from routes used by the public NIC, and it would be intended to be difficult for an external attacker to determine the address of the gateway where these requests go out onto the open internet.

By splitting things up like this, all UDP traffic could be completely blocked by the hosting provider from their public subnet. Someone wanting to do a DDOS couldn’t just attack the normal IP address that they get by doing a DNS lookup – that traffic would all be filtered and never even reach the host. They would need to figure out the UDP gateway from the internal network, but that routing could be changing all of the time.

This confirms my mounting suspicion that many IoT devices are created and used simply Because They Can™, rather than out of any real practical necessity…and that the downside of that faddishness is coming home to roost in their providing a platform for the kind of attacks reported in this article.

None of the consequences have been thought through. It’s sort of like the addiction to politics, wherein doing something because it can be done is justification enough, without regard to the question as to what its consequences will be.

“Because they can” is a newer euphemism for what we used to call “A Solution in search of a Problem” …..!

thgere used to tv show called the dinosaurs – not the momma’s employer was the “we say so corporation” there byline was “we say so”

I know when ARPANET was being developed, they were interested in physical (wires-level) robustness (i.e., in case of war) – but I’m not aware of any scholarly research going on about how to protect TCP/IP from itself.

Patti, those were the days! I used ARPANET on a daily basis back then. Everything was hard wired and we didn’t have the capabilities (good or bad) that we have today.

patti, if you *do* become aware of any academic research in that direction, please let us know!

I’m so glad you are back, Brian!!!

Judging by akamai’s rushed decision – that’s the kind interpretation of their reported sudden ultimatum to Brian – nobody anywhere really has the measure of the www’s potential for packets in any single episode.

You can dodge censorship via one medium if you develop channels in other media.

I suppose it all depends on how serious you want to get

about getting your message out.

As things stand, I’d rely on the www about this much for any vital information, any day, any time; it’s just full o unpatched, flaky software with zero owners and even fuller o unmaintained unbacked-up servers in rooms with unmaintained aircon that packs it in at the first power cut from poorly managed power networks.

And when it works, it’s dominated by big money that

doesn’t exactly hold the pursuit of truth and justice as

core aims…. just the delivery of the latest video and music, and clickbait sports news as cheaply as it can.

Who’d ever think they could engineer integrity into

that kind of fuzz?

The recent accelerating mess of secure certification is a

nice case in point. While everyone tries to support open certification as a true advance, the model of paid

certification persists and persists. And when closely examined, each encryption method has shown plenty o holes.

At each border, someone has their hand out. We from polite first world societies interpret that as an operating tax. Those with other life experience view it more or less as bribery to be dodged or subverted as needed.

The alternative of policing the borders is where it will all end. And closed networks are already the death of

the www.

I gave up on it when journalists began believing they

were able to conduct their professional business over Twitter and Facebook.

Good luck to you Brian.

I hope journalists do manage to set up a viable

alternative network. I’d be pleased to donate.

A usenet style of publishing, for example, has a lot

to recommend it…… distributed servers, nice quiet html-free reading.

reading your blog today, i’ve been encountering outages, so project shield isn’t bomb proof. Is there a site we can watch what the shield is encountering?

“Unfortunately, a huge percentage of the networks that allow spoofing are hosting providers that offer extremely low-cost, virtual private servers (VPS). And these companies will never voluntarily run CAIDA’s spoof-testing tools.”

There have also been a number of publicly-shared tests with the spoofer project’s tools from low-cost VPes over time, presumably by people who are signing up to test them. Many are not filtering, but also many are.

My personal view is that the problem is much wider than hosting providers. If you take a look at networks where we do have data, there are plenty of access networks that are not always filtering, particularly in IPv6. These are going to become a bigger problem with ever-increasing bandwidth provided by access networks.

I am so glad to see you back online. One of the articles about the DDOS attack said the fact that you were attacked means you are doing something right. I totally agree. I have learned a lot reading your articles. Thank you for being you and for being here for us.

I’m wondering how “OVH founder Octave Klaba” knew the attack was “launched by a botnet consisting of more than 145,000 compromised IP cameras and DVRs.”

Did he check them all?

Welcome back! Very interesting read… As a budding network security practitioner, it’s easy to understand the “how” of protection, but it’s another to actually implement. Perhaps that’s what people need to see/hear, more of the “this is what you need to do right now,” to protect themselves, and the Internet at large…

Brian, your story is so powerful. I always knew the threat of cyberwar was real, but I never quite understood it until I read your post and learned what happened to you. We are all very relieved you are up and running again, and are appreciative of your resilience and ability to come out on top, despite the onslaught of attacks against you all these years. You’re got a ton of support out there and we are all behind you – thanks for your courage! Avivah

You don’t mention it in your article or on twitter – are you still under attack now?

I’m interested in this too. How is Google Shield holding up?

I would like to wish you a “Streisand Effect” from this.

Put another way, “May the attempt to shut you up, give you a bigger audience”.

What we need here is someone willing to build a wall to keep out the undesirables…we’ll make them pay for it, in bitcoin.

Keep up the good work, Brian!!

Sorry, somebody beat you to this joke, *and* did it better:

https://twitter.com/geek_at/status/717286863392927744?lang=en

Glad you are back, Brian! It appears that you are now the front man for an initiative against DDOS, and I think you also have some good material for the next book. Just keep us regular users informed, and let us know if there is anything we can do. In the end, I think you will come out much better than the “bad guys”.

Regards,

Akamai can’t be faulted for dropping a pro bono client, but I can’t help wondering whether they have capabilities to defend against modern DDoS attacks for paying customers.

In fairness, there are -zero- reports of Brian’s site going down, or even slowing down, before Akamai/Prolexic cut the cord.

I myself looked at it, after Brian had tweeted that he was under attack (was that Friday or Thursday? I can’t remember now) and the site came up in my browser lickety split.

So, you know, it wasn’t really that they couldn’t handle it. It was more like they could no longer make a case to management that they should be providing Brian with all that bandwidth, for an indefinite stretch of time, going forward, and all for the low low price of only $0.00.

Like Brian, I can’t say as I blame them. They ain’t runnin’ charity after all. But Google Shield is clearly motivated by different goals. Let’s hope that they have the both the pipes and the stones necessary to support those.

Kind of ironic that Google has Project Shield listed on the same website as the AI they’re using to censor what they consider “undesirable” comments and posts.

Google’s censorship (at least according to their guidelines) is limited to “abusive language, threats, and harassment”. With the possible exception of the “language” vector, what bothers you about that? Nothing here about ideology, opinions, ideas, etc. Now, if they go beyond that, I agree there could be a problem.

@Nope, there is no “they” with the Conversation AI project. It is simply a machine learning algorithm utilizing Tensor Flow to generate an attack rating based on content and context to flag comments which it identifies as exceeding the preconfigured rating limits determined by the host implementing the package for use on chair platform. More specifically to your false assertion, you have no right to any speech, let alone free speech, on private networks governed by private entities, this is not censorship, it is an enforcement mechanism for abiding by editorial standards as outlined in community acceptable use policies.

https://www.wired.com/2016/09/inside-googles-internet-justice-league-ai-powered-war-trolls/

Brian, open up a Tor (onion) hidden service.

Are the IoT devices, ISP routers, and DVRs you are describing being modified/configured by the attacker for use in the attack, or are you mostly describing amplification/reflection?

In one case it would mean they could be exploited repeatedly by different parties, and in another case the devices could be locked into working for only one party. That’s what I really wonder about, since someone suggested the devices would be “burned” by being discovered in an attack. If it’s only a reflection attack, I’m sure they wouldn’t be burned. Consumers don’t know, and vendors don’t issue recalls for things like that.

Perhaps if vendors had to be culpable for attacks launched from their devices….

“Perhaps if vendors had to be culpable for attacks launched from their devices….”

In your dreams maybe.

I was thinking about this kind of thing just the other day actually.

I was thiking that, as a first step, maybe we could at least get a law passed, just in California, that would make it civilly actionable to either sell or manufacture any product in the state which (a) is designed so as to be easily connected to the Internet and which also (b) provides some functionality which can only be accessesd by using a password and finally (c) which is sold or shipped with a DEFAULT PASSWORD which is the same among multiple units of the same make and model of device.

This would be a good first step towards at least a tiny bit of sanity on the modern Internet. But precisely because it is so simple and sensible, you would probably have industry lobbists lining up five deep in the hallways of the state legislature to oppose it. In short, as with all things that are this obviously sensible, it probably doesn’t have a prayer in hell of ever coming anywhere near becoming law.

And also, actually, even this kind of law probably wouldn’t have made a damn bit of difference in Brian’s case. The problem in this case (and in the case of OVH, apparently) seems to be that virtually all IP-CCTV systems are just re-labeled (by at least 70 different vendors) but they are all manufactured by one single manufacturer in the Far East, and thus, they ALL have (at least) one Really Bad Bug that you don’t even need to log into the things in order to exploit.

Someday maybe, the U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission might give a rat’s ass about this kind of crap, but probably not in my lifetime. Too many lobbists already hate the fact that the comission even exists, or that it even does stuff like stopping people from selling highly flammable babywear.

The Captains of Industry in America drone on endlessly about what wonderful miracles the Internet and modern software are “because they have been allowed to flourish without unnecessary constrains imposed in the form of government regulation”. Nobody ever mentions the downside of allowing any nit-wit to ship whatever crap IoT thing he or she wants. Now at least, a few more people appreciate that there *is* in fact a downside.

The devices that hit my network were IoT and TCP connections only. No UDP and no amplification or reflection.

That’s not to say the IoT botnet could not have been used for DNS-based attacks, which is even more terrifying.

There are two problems here contributing to the same overall threat. Both need to be addressed.

Very well written and definitely these pointers are action items for the global Internet community !!

look past this example, connect the dots, see bigger elements in play. no, there will be no coalitions formed to counter this weapon, for the nominated actors that could push such alliances into effect are in fact themselves that would utilize and benefit most from this very threat….

Privatisation of Censorship is nothing new, some states have been running this strategy for decades. Internet is merely new frontier. Make no mistake, it’s all planned. New World will be a superficial utopia, but It was never meant to be pretty…

wE won’t say S0RRY…