When KrebsOnSecurity recently explored how cybercriminals were using hacked email accounts at police departments worldwide to obtain warrantless Emergency Data Requests (EDRs) from social media firms and technology providers, many security experts called it a fundamentally unfixable problem. But don’t tell that to Matt Donahue, a former FBI agent who recently quit the agency to launch a startup that aims to help tech companies do a better job screening out phony law enforcement data requests — in part by assigning trustworthiness or “credit ratings” to law enforcement authorities worldwide.

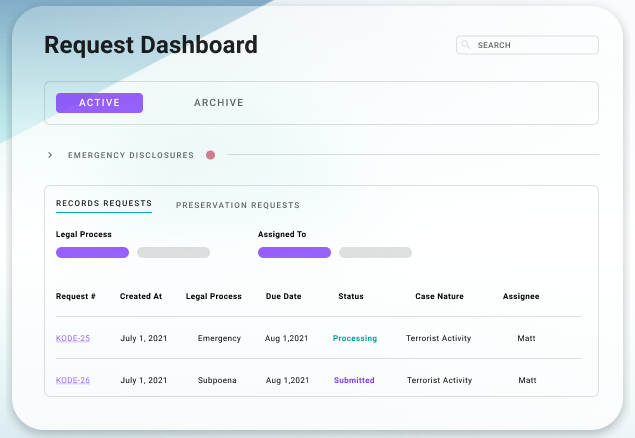

A sample Kodex dashboard. Image: Kodex.us.

Donahue is co-founder of Kodex, a company formed in February 2021 that builds security portals designed to help tech companies “manage information requests from government agencies who contact them, and to securely transfer data & collaborate against abuses on their platform.”

The 30-year-old Donahue said he left the FBI in April 2020 to start Kodex because it was clear that social media and technology companies needed help validating the increasingly large number of law enforcement requests domestically and internationally.

“So much of this is such an antiquated, manual process,” Donahue said of his perspective gained at the FBI. “In a lot of cases we’re still sending faxes when more secure and expedient technologies exist.”

Donahue said when he brought the subject up with his superiors at the FBI, they would kind of shrug it off, as if to say, “This is how it’s done and there’s no changing it.”

“My bosses told me I was committing career suicide doing this, but I genuinely believe fixing this process will do more for national security than a 20-year career at the FBI,” he said. “This is such a bigger problem than people give it credit for, and that’s why I left the bureau to start this company.”

One of the stated goals of Kodex is to build a scoring or reputation system for law enforcement personnel who make these data requests. After all, there are tens of thousands of police jurisdictions around the world — including roughly 18,000 in the United States alone — and all it takes for hackers to abuse the EDR process is illicit access to a single police email account.

Kodex is trying to tackle the problem of fake EDRs by working directly with the data providers to pool information about police or government officials submitting these requests, and hopefully making it easier for all customers to spot an unauthorized EDR.

Kodex’s first big client was cryptocurrency giant Coinbase, which confirmed their partnership but otherwise declined to comment for this story. Twilio confirmed it uses Kodex’s technology for law enforcement requests destined for any of its business units, but likewise declined to comment further.

Within their own separate Kodex portals, Twilio can’t see requests submitted to Coinbase, or vice versa. But each can see if a law enforcement entity or individual tied to one of their own requests has ever submitted a request to a different Kodex client, and then drill down further into other data about the submitter, such as Internet address(es) used, and the age of the requestor’s email address.

Donahue said in Kodex’s system, each law enforcement entity is assigned a credit rating, wherein officials who have a long history of sending valid legal requests will have a higher rating than someone sending an EDR for the first time.

“In those cases, we warn the customer with a flash on the request when it pops up that we’re allowing this to come through because the email was verified [as being sent from a valid police or government domain name], but we’re trying to verify the emergency situation for you, and we will change that rating once we get new information about the emergency,” Donahue said.

“This way, even if one customer gets a fake request, we’re able to prevent it from happening to someone else,” he continued. “In a lot of cases with fake EDRs, you can see the same email [address] being used to message different companies for data. And that’s the problem: So many companies are operating in their own silos and are not able to share information about what they’re seeing, which is why we’re seeing scammers exploit this good faith process of EDRs.”

NEEDLES IN THE HAYSTACK

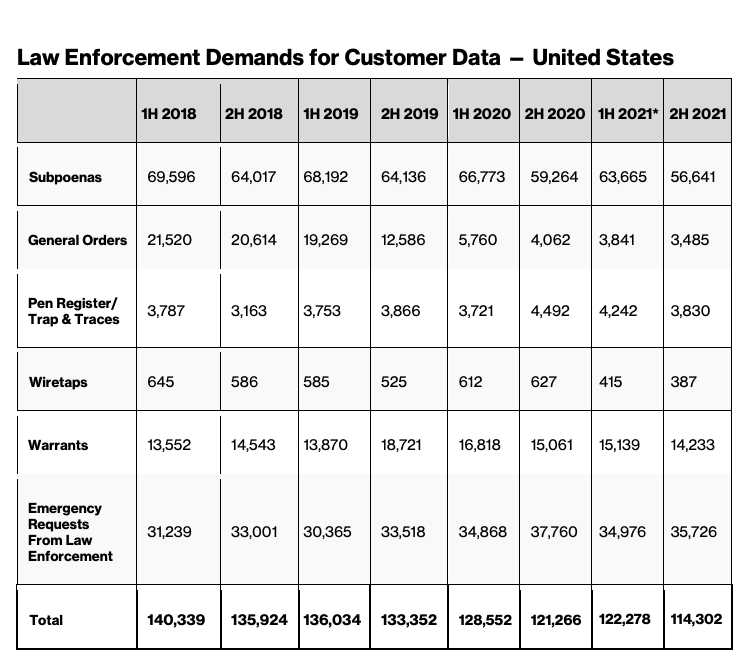

As social media and technology platforms have grown over the years, so have the volumes of requests from law enforcement agencies worldwide for user data. For example, in its latest transparency report mobile giant Verizon reported receiving 114,000 data requests of all types from U.S. law enforcement entities in the second half of 2021.

Verizon said approximately 35,000 of those requests (~30 percent) were EDRs, and that it provided data in roughly 91 percent of those cases. The company doesn’t disclose how many EDRs came from foreign law enforcement entities during that same time period. Verizon currently asks law enforcement officials to send these requests via fax.

Validating legal requests by domain name may be fine for data demands that include documents like subpoenas and search warrants, which can be validated with the courts. But not so for EDRs, which largely bypass any official review and do not require the requestor to submit any court-approved documents.

Police and government authorities can legitimately request EDRs to learn the whereabouts or identities of people who have posted online about plans to harm themselves or others, or in other exigent circumstances such as a child abduction or abuse, or a potential terrorist attack.

But as KrebsOnSecurity reported in March, it is now clear that crooks have figured out there is no quick and easy way for a company that receives one of these EDRs to know whether it is legitimate. Using illicit access to hacked police email accounts, the attackers will send a fake EDR along with an attestation that innocent people will likely suffer greatly or die unless the requested data is provided immediately.

In this scenario, the receiving company finds itself caught between two unsavory outcomes: Failing to immediately comply with an EDR — and potentially having someone’s blood on their hands — or possibly leaking a customer record to the wrong person. That might explain why the compliance rate for EDRs is usually quite high — often upwards of 90 percent.

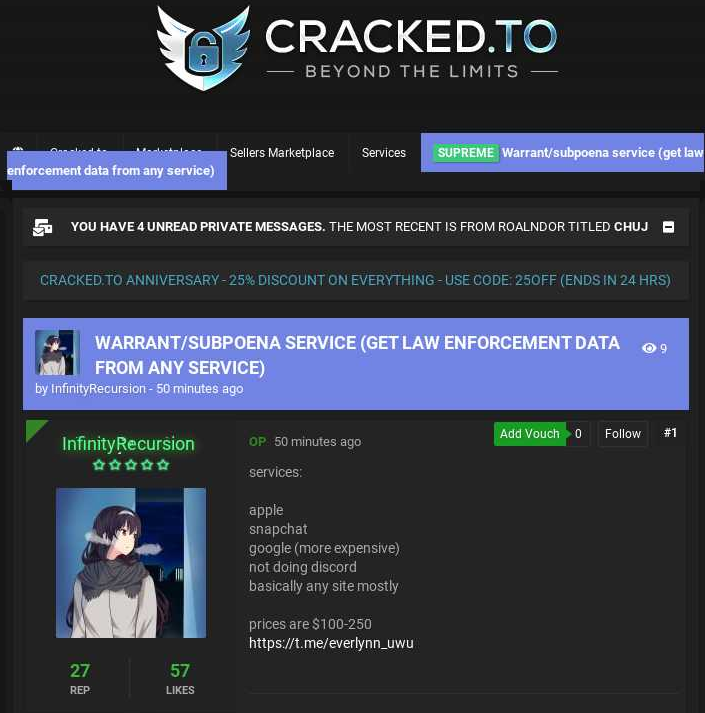

Fake EDRs have become such a reliable method in the cybercrime underground for obtaining information about account holders that several cybercriminals have started offering services that will submit these fraudulent EDRs on behalf of paying clients to a number of top social media and technology firms.

A fake EDR service advertised on a hacker forum in 2021.

An individual who’s part of the community of crooks that are abusing fake EDR told KrebsOnSecurity the schemes often involve hacking into police department emails by first compromising the agency’s website. From there, they can drop a backdoor “shell” on the server to secure permanent access, and then create new email accounts within the hacked organization.

In other cases, hackers will try to guess the passwords of police department email systems. In these attacks, the hackers will identify email addresses associated with law enforcement personnel, and then attempt to authenticate using passwords those individuals have used at other websites that have been breached previously.

EDR OVERLOAD?

Donahue said depending on the industry, EDRs make up between 5 percent and 30 percent of the total volume of requests. In contrast, he said, EDRs amount to less than three percent of the requests sent through Kodex portals used by customers.

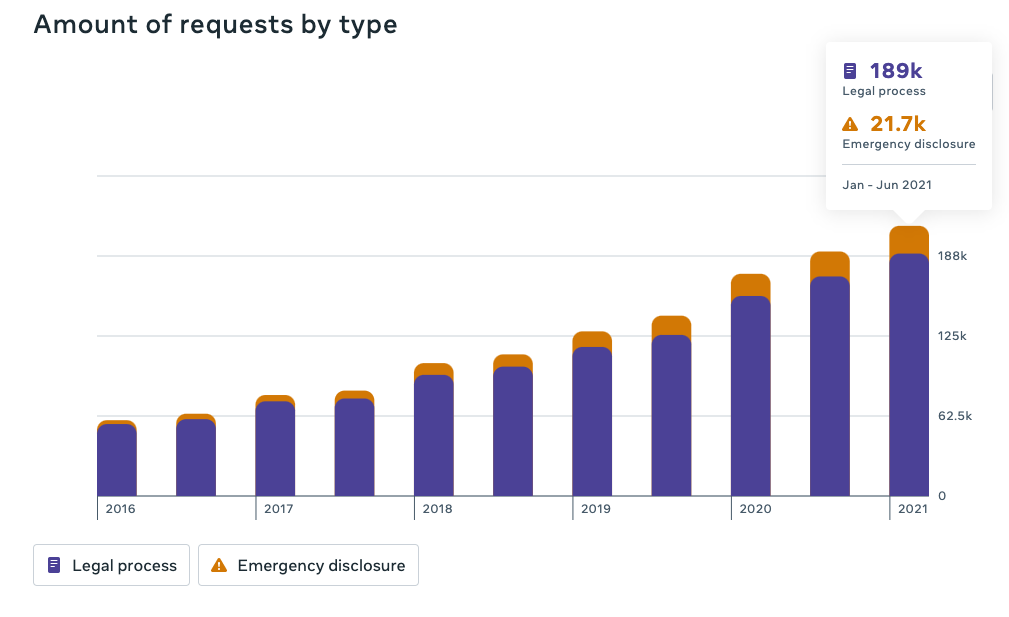

KrebsOnSecurity sought to verify those numbers by compiling EDR statistics based on annual or semi-annual transparency reports from some of the largest technology and social media firms. While there are no available figures on the number of fake EDRs each provider is receiving each year, those phony requests can easily hide amid an increasingly heavy torrent of legitimate demands.

Meta/Facebook says roughly 11 percent of all law enforcement data requests — 21,700 of them — were EDRs in the first half of 2021. Almost 80 percent of the time the company produced at least some data in response. Facebook has long used its own online portal where law enforcement officials must first register before submitting requests.

Government data requests, including EDRs, received by Facebook over the years. Image: Meta Transparency Report.

Apple said it received 1,162 emergency requests for data in the last reporting period it made public — July – December 2020. Apple’s compliance with EDRs was 93 percent worldwide in 2020. Apple’s website says it accepts EDRs via email, after applicants have filled out a supplied PDF form. [As a lifelong Apple user and customer, I was floored to learn that the richest company in the world — which for several years has banked heavily on privacy and security promises to customers — still relies on email for such sensitive requests].

Twitter says it received 1,860 EDRs in the first half of 2021, or roughly 15 percent of the global information requests sent to Twitter. Twitter accepts EDRs via an interactive form on the company’s website. Twitter reports that EDRs decreased by 25% during this reporting period, while the aggregate number of accounts specified in these requests decreased by 15%. The United States submitted the highest volume of global emergency requests (36%), followed by Japan (19%), and India (12%).

Discord reported receiving 378 requests for emergency data disclosure in the first half of 2021. Discord accepts EDRs via a specified email address.

For the six months ending in December 2021, Snapchat said it received 2,085 EDRs from authorities in the United States (with a 59 percent compliance rate), and another 1,448 from international police (64 percent granted). Snapchat has a form for submitting EDRs on its website.

TikTok‘s resources on government data requests currently lead to a “Page not found” error, but a company spokesperson said TikTok received 715 EDRs in the first half of 2021. That’s up from 409 EDRs in the previous six months. Tiktok handles EDRs via a form on its website.

The current transparency reports for both Google and Microsoft do not break out EDRs by category. Microsoft says that in the second half of 2021 it received more than 25,000 government requests, and that it complied at least partly with those requests more than 90 percent of the time.

Microsoft runs its own portal that law enforcement officials must register at to submit legal requests, but that portal doesn’t accept requests for other Microsoft properties, such as LinkedIn or Github.

Google said it received more than 113,000 government requests for user data in the last half of 2020, and that about 76 percent of the requests resulted in the disclosure of some user information. Google doesn’t publish EDR numbers, and it did not respond to requests for those figures. Google also runs its own portal for accepting law enforcement data requests.

Verizon reports (PDF) receiving more than 35,000 EDRs from just U.S. law enforcement in the second half of 2021, out of a total of 114,000 law enforcement requests (Verizon doesn’t disclose how many EDRs came from foreign law enforcement entities). Verizon said it complied with approximately 91 percent of requests. The company accepts law enforcement requests via snail mail or fax.

Image: Verizon.com.

AT&T says (PDF) it received nearly 19,000 EDRs in the second half of 2021; it provided some data roughly 95 percent of the time. AT&T requires EDRs to be faxed.

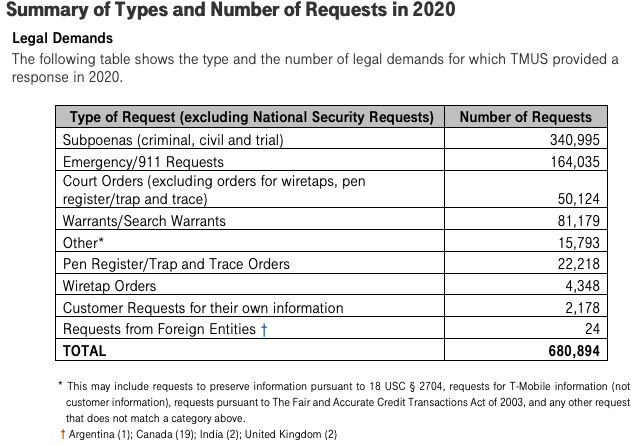

The most recent transparency report published by T-Mobile says the company received more than 164,000 “emergency/911” requests in 2020 — but it does not specifically call out EDRs. Like its old school telco brethren, T-Mobile requires EDRs to be faxed. T-Mobile did not respond to requests for more information.

Data from T-Mobile’s most recent transparency report in 2020. Image: T-Mobile.

From my experience, Kodex should assume it is the target of serious espionage groups. Did you get an impression in your conversation with Matt Donahue that he has the resources to fight that off, or at least detect it if it happens?

Yes, the issue of Kodex becoming a big target certainly came up. Donahue said they were definitely aware of that and had engineered their platform to segment access, so that each customer is in their own silo. But I’m sure he can chime in here if he wants and add more perspective there.

This has always been top of mind from day one – security is our top priority. Companies are already targets on their own, and they are fighting in the dark with limited resources – sharing resources they can help protect each other.

This strikes me as indicative of the trends that went unchecked in the dot com boom/bomb when those in charge would not listen to those at the core of development and analysis. Big Gov has earned a reputation for purchasing gold toilet seats unchecked. And now we see that the sectors that serve to protect are apparently bogged down in having hierarchical BS so deep that obvious flaws must be taken outside to be fixed. How many layers of the FBI and government security are responsible for this? How many will be held accountable?

How much will result in more spending on an agency apparently incapable of doing its job? If that section of the FBI was a public company it would be toast, but because it is government it will continue and the people from within that are smart enough to have seen the problem will go out and create solutions… and the public will end up paying for the services provided through underlying contracts with service providers and paid by local governments attempting to reduce fraud. But will we be paying less in the bigger scheme of tax dollars to the FBI and government sectors of security?

Maybe I am a bit cynical but I bet if there was a credit card charge for each request much of the fraud would be gone.

What am I missing? Are the EDRs so frequent that the provider of the data can’t make a quick phone call to the entity making the request to verify it’s a legitimate request? How many requests for EDRs per day does Google get that they don’t have sufficient staff to verify the source of the request? An email address shouldn’t be sufficient to authenticate a request. There should be at least a three part authentication process?

You beat me to it! If the exploit is almost entirely relying on only a breached/malicious email address, verify the request via a second known method.

Surely at least for the US agencies it couldn’t be that difficult to put together a directory of verified contact numbers for each agency. Call through to their agency and ask “could you please confirm that your agency has submitted request #XYZ123”.

It would then require an attacker to either change the directory containing the known phone numbers, or to be an insider at the agency.

A phone call alone (to a number NOT supplied by the requestor) must knock out 95% or more of this problem. Not sure why this isn’t obvious …or am I (we) missing something?

That’s the default solution most people suggest first.

Very easy to suggest, but actually quite difficult in practice. Maintaining a constantly changing database with no legal requirement to participate is a real challenge. It’s no wonder that the solution proposed here is decentralized and reputation based.

You know nothing about it and no, the solution is centralized authenticated and distributed db based.

“the solution is centralized authenticated and distributed db based”

^ This comment, on the same day as this article: “DEA says it is investigating reports that hackers gained unauthorized access to an agency portal that taps into 16 different federal law enforcement databases”

Which means, most likely, that the DEA didn’t have proper security setup.

You are also comparing one breached account (in regards to the DEA) to hundreds/thousands of breached email (which is going to have lesser security than a federal database) used in part of EDR’s.

It is not insurmountable to perform minimal security, just as LE is expected to to in its other duties, like investigation, evidence gathering, chain of custody etc.

Don’t make excuses for incompetence or laziness by suggesting more laziness.

“the solution is centralized authenticated and distributed db based”

^ This comment, on the same day as this article: “DEA says it is investigating reports that hackers gained unauthorized access to an agency portal that taps into 16 different federal law enforcement databases”

It would actually be pitifully easy to enforce. We do this now with purchasing requests in the IT world, so pretending it is impossible for LE to do is ridiculous.

What it comes down to is that LE likes the lax process, so that they can use the EDR process for very weak/flimsy reasons, without any checks.

Give me a break, anyone who has been in IT more than a year or two knows you are full of it.

18,000 law enforcement agencies, each with hundreds if not thousands of employees, and the same turnover issues that any other entity has these days. You would have to maintain somewhere around a million phone numbers. Then you would have to employ enough staff to reach out and confirm identity. T Mobile says it had 165,000 such requests in 2020. So call it a three minute phone call for each, that’s 8,250 staff hours for T Mobile alone. And that’s assuming every law enforcement officer is waiting for your call, which I can tell you from experience is almost never the case.

Because 1 million is way too big for a managed database, says the non-dev.

Any idiot can be a dev. Like idiots who don’t understand it’s not the number of rows in a database, it’s the complexity of the process to update each row if it keeps changing as thousands of external third parties churn through people.

Any idiot can reduce a complex problem to intractable via loose talk also ^

but that doesn’t make it so. Validated credentials or they don’t access.

It’s a solvable problem even for an idiot pretending to be a dev.

Nobody would pretend to be a dev they are the cheap laborers of the IT workforce.

Nobody except an imposter pretending to be a dev constantly.

Speaking as an *diot pretending to be a dev are we?

This is an entirely solvable issue Mr. dataphobe.

Nobody would pretend to be a dev they are the cheap laborers of the IT workforce and the first to be outsourced to India.

“I like to pretend to be other people here.”

-JamminJ

where’s that from?

*(It’s filed under other people’s names, to impersonate them.)

**(Like you just did again, JamminJ, as Brian is aware of)

what other people? you mean brian the author?

I can tell you from my experience, it doesn’t matter the size of the database. Rather it is the fact that the data changes and is completely outside of our control. 18,000 law enforcement agencies, each with hundreds if not thousands of employees and the same turnover issues that any other entity has these days. Who is managing this mythical database?

I’ve been reading Krebs for a long time now. What’s being a non-developer have to do with anything?

Its a good thing that we have companies which already do this, huh?

You do know that police agencies have a process for ‘On-Call,’ right? Even outside of 911.

In fact, there is also a judge ‘On-Call,’ for warrants (or the like, they have varying names). You knew that, right?

Then we can look at the very absurdity of your claim that 18k agencies is something large, that companies do not already monitor. Agencies will have a contract with a local carrier; this is because they have department cell phones, they have SIM cards in their patrol cars, their radios actually tie into the phone system etc. So there is a lot of tie into to communications, and other agencies, for a department simply to exist.

Sure, a department that just “SPRUNG INTO EXISTENCE!” might have an issue, but how often is a new agency/department being formed?

Get real, and try tour story on people who haven’t been in LE and IT.

this may not be related but Moody’s and various fin rating agencies rated junk debt as AAA investments..

focus on verification security in an in depth security stance.

please watch out for employees falling pray to the fast easy money.

decent security will occur and the money will come if the main focus is on protecting employees who are trying to do their job for all society to function.

redundant and thanks capt obvious.. but again.. people before profits

You seem Professional 🙂

hopefully another bronze age collapse can be avoided or a weird new dark age won’t come about..

You don’t really.

From the table above, Verizon deals with over 700 requests a day, more than 100 of which are these emergency requests. I’m sure companies want to staff the absolute minimum number of people necessary to comply with these requests so it makes sense that they just err on the side of complying with the requests. I’m sure it takes long enough just to compile the data needed from various systems within the company for many of them, so when an emergency request comes through that requires minimal data they send and move on.

There is virtually zero risk (to the company) in complying and significant risk to failing to comply, so the ‘credit’ system described above really adds a lot of value as it would be made instantly obvious that a request is highly problematic, whereas right now there is no way to tell without adding significant labor burden.

“… many security experts called it a fundamentally unfixable problem …”

Oh hell no, Sparky. Learn the difference between a “Computer” and the “Web”

Top Secret Rosie’s (2010)

Hidden Figures (2016)

… And don’t say Melinda French Gates (or MacKenzie Scott Bezos) didn’t warn you what would happen if you didn’t let girlz in the AI Club House.

{:-)

A good amount of those requests are for account information regarding CSAM

“…scoring or reputation system for law enforcement personnel”

Couldn’t social media companies use a similar “sender and URL reputation filtering” method to filter out the garbage they collect. Maybe put a score at the bottom of a post. Don’t use social media so I’m not sure what it would look like. Sorry I’m a little off topic.

If these come from all over the world and there is no verification, I’m wondering if you even need to hack an email account. Can’t someone just set up a fake domain for a real or fake police department?

Seems like a good faith attempt to solve a very serious problem. I hope the results are significant.

With only some companies providing stats, and those only showing the rate at which they comply with an EDR, is it even possible to determine if self-hosted web portals with the requirements to pre-register makes a huge difference compared to email?

EDRs? Whatever happened to due-process and verifying law enforcement requirements using information obtained out-of-band (i.e a court order signed by a judge and verified with said court)?

Yeah, right. Sorry, but that doesn’t happen like in the movies.

Basically, unless you have $20k+ to fight a case, you’ll lose or have to plea out/down.

I know there are disadvantages, but why not require something like oauth on the portal, using the credentials used for FBI background checks, or conceal permits, or drivers license blah. Maybe we just don’t hear about it, but breaches of these databases are less frequent.

Many smaller police departments have no dedicated IT staff, so relying on email and it’s security doesn’t make as much sense.

It would be easy.

Create an application, and verification process, using MFA and multiple means of contact at each data hold they would like to request an EDR through.

Thank you for bringing your best to work every single day.

Who names these companies? Does Kodex sound like a feminine unmentionable product to You? Now way to correct any data. Unless an arrest is made. Then a giant lawsuit against the enforcement agency. Is Kodex an acronym?

AT&T requires EDRs to be faxed. So I googled “AT&T EDRs fax number?”… Costs $7000.00 Seven Grand! Per Month. Cost alot less to setup your own fake site and get paid. Nigerian Companies Unite!

Bring on the Spoofed Sites, since most underfunded law enforcement agencies are great at checking credentials.

Just another rant. Lets do an article on making fake sites. Hire your local GRAPHIC DESIGNER/ WEB DEV. THEN ACTUALLY PAY THEM ON TIME.

GOOGLE THE POLITICIAN WHO HIRED One then, Didn’t pay. Hawaii.

~LOVE TO KREBS

Is Kodex going to include in their validation process some way to measure how well a US LEA is doing at protecting its Web NCIC portals? That failure mode should be a strong indicator of whether OpSec there is taken seriously.

Some may recall that in the 90s a Northern Virginia police department and the Indiana State Police both notoriously thought that not having a DNS name attached to the IP address of their internet connection IIS 3.0 servers was sufficient to keep baddies away. Some departments clearly should not be allowed to handle sharp objects…it was so bad the FBI was proactively providing Solaris firewalls to some of the worst offenders.

Nobody will take me seriously about this but I’ve been following this WHOLE story watching it unfold for 5 1/2 years. Its a lot more than hacking into LE databases. There are a few articles Brian Krebs has written regarding the investigation of this whole case but I’m not sure if he knows that the other articles relate to this one. I’m a victim of these criminals and its taken years to get me (almost) free from it all.