When you’re planning to rob the Russian cyber mob, you’d better make sure that you have the element of surprise, that you can make a clean getaway, and that you understand how your target is going to respond. Today’s column features an interview with two security experts who helped plan and execute last week’s global, collaborative effort to hijack the Gameover Zeus botnet, an extremely resilient and sophisticated crime machine that helped an elite group of thieves steal more than $100 million from banks, businesses and consumers worldwide.

Neither expert I spoke with wished to be identified for this story, citing a lack of permission from their employers and a desire to remain off the radar of the crooks inconvenienced by the action. For obvious reasons, they were also reluctant to share details about the exact weaknesses that were used to hijack the botnet, focusing instead on the planning and and preparation that went into this effort.

GAMEOVER ZEUS PRIMER

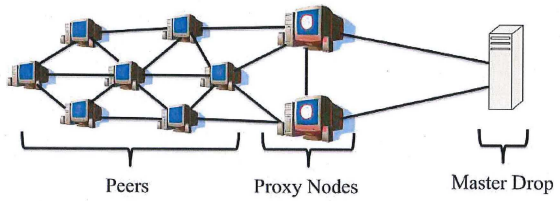

A quick review of how Gameover works should help readers get more out of the interview. In traditional botnets, infected PCs report home to and are controlled by a central server. But this architecture leaves such botnets vulnerable to disruption or takeover if authorities or security experts can gain access to the control server.

Gameover, on the other hand, is a peer-to-peer (P2P) botnet designed as a collection of small networks that are distinct but linked up in a decentralized fashion. The individual Gameover-infected PCs are known as “peers.” Above the peers are a select number of slightly more powerful and important infected systems that are assigned roles as “proxy nodes,” meaning they were selected from the peers to serve as relay points for commands coming from the Gameover botnet operators and as conduits for encrypted data stolen from the infected systems.

The Gameover botnet code also includes a failsafe mechanism that can be invoked if the botnet’s P2P communications system fails, whether the failure is the result of a faulty malware update or because of a takedown effort by researchers/law enforcement. That failsafe is a domain generation algorithm (DGA) component that generates a list of 1,000 domain names each week (gibberish domains that are essentially long jumbles of letters) combined with one of six top-level domains; .com, .net, .org, .biz, .info and .ru. In the event the infected Gameover systems can’t get new instructions from their peers, the code instructs the botted systems to seek out domains from the latest list of 1,000 domains generated by the DGA until it finds a site with new instructions.

HUNDREDS OF ‘WEB INJECTS’

The Gameover malware was designed specifically to defeat two-factor authentication used by many banks. It did so using a huge collection of custom-made scripts known as “Web injects” that can inject custom content into a Web browser when the victim browses to certain sites — such as a specific bank’s login page. Web injects also are used to prompt the victim to enter additional personal information when they log in to a trusted site. An example of this type of Web inject can be seen in the video below, which shows an inject designed for Citibank customers.

One of the most common Web injects used by ZeuS (including the Gameover variant discussed in this post) will intercept the one-time token code used by many banks as a second authentication factor, then redirect the victim to fake page falsely stating that the bank’s site is temporarily down for maintenance; all the while, the thieves are using the victim’s username, password and stolen one-time code to log in and move money out of the account.

According to CSIS Security Group, a Danish security firm, the crooks in control of Gameover had approximately 1,500 unique Web injects at their disposal that were custom-made to manipulate the display of more than 700 financial institution Web sites around the globe. CSIS shared that complete list, available here as a PDF and here as CSV. One thing you’ll notice is the conspicuous and complete absence of banks in Russia and in the former Soviet satellite countries.

READY PLAYER ONE

In the interview below, this author is “BK”; the interviewees, we’ll call them “Ready Player 1,” and “Ready Player 2,” or RP1 and RP2 for short.

BK: For this takedown to work, you guys had to…

RP1: It’s not a takedown. It’s a takeover. We’re taking control over the botnet.

BK: Right. So how did you all go about taking over the P2P portion of Gameover?

RP2: We don’t want to disclose too much of that because it’s theoretically possible they could regain control. But basically, you have to somehow manipulate the peer list and redirect traffic to yourself. That’s what we’re doing on the proxy node layer and on the P2P layer. And right now we’re controlling that. The [bad guys] can’t propagate updates or control it anymore.

BK: So you guys had to basically disrupt the P2P network and then take the domain names generated by the DGA out of the picture, correct?

RP2: Yes, the DGA is the fallback channel. So, just to be on the safe side, every bot checks in like twice a week and pulls a new list from the DGA. All attacks against P2P networks are pointless if you don’t take care of the DGA as well.

BK: I noticed the Russian top-level domain (TLD) .ru was among the the TLDs from which the takeover effort had to get cooperation. Was that difficult?

RP1: Dot-ru is always a challenge. But in the DNS community…people know each other and that was helpful.

BK: Have you ever seen a case in which the Gameover Zeus botmasters invoked the DGA component after losing control over their botnet?

RP1: This happened a few times in the past. At one point there was a broken version of Gameover, and they registered a few of the domains in the DGA list. There was a bug in version 2 that prevented them from updating it over P2P. I don’t know if the main botnet guy was on vacation that day or what, but something didn’t work right and they were for a while there relying only on the DGA.

BK: This is not the first attempt at takeover Gameover Zeus. Previous efforts didn’t work so well. What makes you think this takeover is going to last?

RP1: In previous P2P poisoning attacks against this botnet, we didn’t fully understand it. The first attack against it, we were not aware of the proxy layer, and that the bots were still able to communicate with the back-end [controller] through that layer. But we’ve been studying this botnet for two-and-a-half years now, so we know it pretty well.

BK: But they made improvements each time a takeover attempt was made right?

RP1: Defending a system that is as complex as this one is very hard. Complexity is the enemy of security. I won’t go into specifics, but let’s just say there are examples in the code where they clearly overreacted and introduced features that we could later use against them. The guys who built this are probably the elite guys in the cybercrime world, and so they really tried to build a botnet that was resilient to takeovers. But the Zeus guys didn’t get it right. They were pretty close to that, but they didn’t get it completely right.

BK: Well, one criticism of these takeovers and takedowns is that the bad guys don’t go away, they just get mad, learn from their mistakes and build a better mousetrap the next time. Don’t these actions merely poke the bear, and encourage them to innovate in ways that could bring us far more potent threats?

RP1: That’s certainly what we’ve seen in the past. They studied our attacks and the stuff that people published about the attacks, and they hardened the botnet. It takes a scientist or a skilled researcher to build a truly resilient P2P network, and these guys are criminals. They built it for stealing, and they don’t have endless resources to study the state-of-the-art, and that’s why they make mistakes.

BK: Were you guys surprised by anything in this takeover? Did anything happen that you weren’t expecting?

RP1: There can always be surprises. But I was a little surprised that they didn’t fight back. We were prepared for that. You have to be prepared for the unexpected, but that didn’t happen in this case.

BK: What have you noticed now that you have control over this botnet?

RP1: They were very active in using it. You’ve heard about cryptolocker. They had a very professional infrastructure set up so that most of this stuff was automated. The maintenance of the botnet was automated for the most part, and they also worked hard to keep the number of infected machines high over time. In order to stay in the game, they had to reinfect new machines all the time. And they did that with spam campaigns. It was a very professional organization.

BK: Right, they primarily used Cutwail to spread Gameover, correct?

RP2: Correct, and there’s been almost no Cutwail spam since last Friday.

BK: So, from your perspective, how did the Gameover guys use the data-theft component of this botnet, aside from the well-known financial attacks and account takeovers that reportedly netted them more than $100 million?

RP1: This was an information-gathering botnet. Everyone hears Zeus and they automatically think banking Trojan. But they were harvesting more than that.

BK: Have you all seen signs that the guys running this botnet were looking for stuff on infected machines that went beyond financial data?

RP1: I saw some, yes, but I can’t really talk about that. They were definitely looking for proprietary information in some cases.

BK: So the attack on Gameover began late last week, but how long was it before you guys felt like you had control over it, so that the botmasters couldn’t get it back.

RP1: Attacks against P2P networks usually take some time, depending on the specific implementation of the protocol. And at some point you own a critical mass and then it’s under your control. But it’s hard for us to tell when that happened.

BK: Why’s that?

RP1: It’s not trivial to monitor these things. You don’t have visibility into the entire botnet. Your view might be limited, but if you don’t see any changes over certain period of time, you can be sure the botnet is stable.

So far, the takeover appears to be holding steady. According to RP1 and RP2, a number of ISPs worldwide have begun notifying affected customers and trying to help with the cleanup process. For now, the number of new infections from Gameover Zeus have dropped to zero, according to Heimdal Security, a Danish security firm.

Hi Brian,

Any news from behind the scenes?

The implication of the article is it’s distinctly possible that, as good or better than the Conficker take-down, GOZ might be permanently mitigated via actual compromise and takeover of the botnet.

Over the last few weeks I have observed a huge decline in both spam connection attempts and successful bypass of anti-UCE in the MTA here. Also see a decrease in RDP brute-force activity of the relatively smart variety.

Such falloffs occur, and perhaps correspond with vacation time in the black-hat world, but on can hope the demise of GOZ is at work here.

David