Microsoft today released security updates to fix almost a hundred flaws in its various Windows operating systems and related software. One bug is so serious that Microsoft is issuing patches for it on Windows XP and other operating systems the company no longer officially supports. Separately, Adobe has pushed critical updates for its Flash and Shockwave players, two programs most users would probably be better off without.

According to security firm Qualys, 27 of the 94 security holes Microsoft patches with today’s release can be exploited remotely by malware or miscreants to seize complete control over vulnerable systems with little or no interaction on the part of the user.

According to security firm Qualys, 27 of the 94 security holes Microsoft patches with today’s release can be exploited remotely by malware or miscreants to seize complete control over vulnerable systems with little or no interaction on the part of the user.

Microsoft this month is fixing another serious flaw (CVE-2017-8543) present in most versions of Windows that resides in the feature of the operating system which handles file and printer sharing (also known as “Server Message Block” or the SMB service).

SMB vulnerabilities can be extremely dangerous if left unpatched on a local (internal) corporate network. That’s because a single piece of malware that exploits this SMB flaw within a network could be used to replicate itself to all vulnerable systems very quickly.

It is this very “wormlike” capability — a flaw in Microsoft’s SMB service — that was harnessed for spreading by WannaCry, the global ransomware contagion last month that held files for ransom at countless organizations and shut down at least 16 hospitals in the United Kingdom.

According to Microsoft, this newer SMB flaw is already being exploited in the wild. The vulnerability affects Windows Server 2016, 2012, 2008 as well as desktop systems like Windows 10, 7 and 8.1.

The SMB flaw — like the one that WannaCry leveraged — also affects older, unsupported versions of Windows such as Windows XP and Windows Server 2003. And, as with that SMB flaw, Microsoft has made the unusual decision to make fixes for this newer SMB bug available for those older versions. Users running XP or Server 2003 can get the update for this flaw here.

“Our decision today to release these security updates for platforms not in extended support should not be viewed as a departure from our standard servicing policies,” wrote Eric Doerr, general manager of Microsoft’s Security Response Center.

“Based on an assessment of the current threat landscape by our security engineers, we made the decision to make updates available more broadly,” Doerr wrote. “As always, we recommend customers upgrade to the latest platforms. “The best protection is to be on a modern, up-to-date system that incorporates the latest defense-in-depth innovations. Older systems, even if fully up-to-date, lack the latest security features and advancements.”

The default browsers on Windows — Internet Explorer or Edge — get their usual slew of updates this month for many of these critical, remotely exploitable bugs. Qualys says organizations using Microsoft Outlook should pay special attention to a newly patched bug in the popular mail program because attackers can send malicious email and take complete control over the recipient’s Windows machine when users merely view a specially crafted email in Outlook. Continue reading

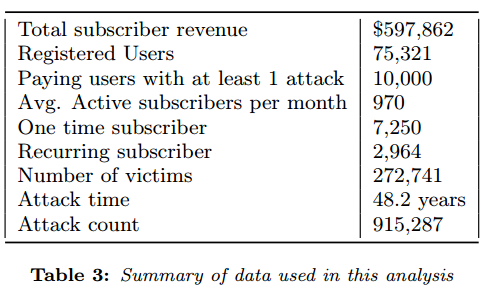

The NYU researchers found that vDOS had extremely low costs, and virtually all of its business was profit. Customers would pay up front for a subscription to the service, which was sold in booter packages priced from $5 to $300. The prices were based partly on the overall number of seconds that an attack may last (e.g., an hour would be 3,600 worth of attack seconds).

The NYU researchers found that vDOS had extremely low costs, and virtually all of its business was profit. Customers would pay up front for a subscription to the service, which was sold in booter packages priced from $5 to $300. The prices were based partly on the overall number of seconds that an attack may last (e.g., an hour would be 3,600 worth of attack seconds). Headquartered in San Francisco, OneLogin provides single sign-on and identity management for cloud-base applications. OneLogin counts among its customers some 2,000 companies in 44 countries, over 300 app vendors and more than 70 software-as-a-service providers.

Headquartered in San Francisco, OneLogin provides single sign-on and identity management for cloud-base applications. OneLogin counts among its customers some 2,000 companies in 44 countries, over 300 app vendors and more than 70 software-as-a-service providers.

In April 2017 I received an anonymous tip from a reader who said he’d figured out that just by changing a single number in the Web address when accessing his recent medical claim at MolinaHealthcare.com he could then view any and all other patient claims.

In April 2017 I received an anonymous tip from a reader who said he’d figured out that just by changing a single number in the Web address when accessing his recent medical claim at MolinaHealthcare.com he could then view any and all other patient claims.