A new report proves the value of following the money in the fight against dodgy cybercrime services known as “booters” or “stressers” — virtual hired muscle that can be rented to knock nearly any website offline.

Last fall, two 18-year-old Israeli men were arrested for allegedly running vDOS, perhaps the most successful booter service of all time. The young men were detained within hours of being named in a story on this blog as the co-proprietors of the service (KrebsOnSecurity.com would later suffer a three-day outage as a result of an attack that was alleged to have been purchased in retribution for my reporting on vDOS).

The vDos home page.

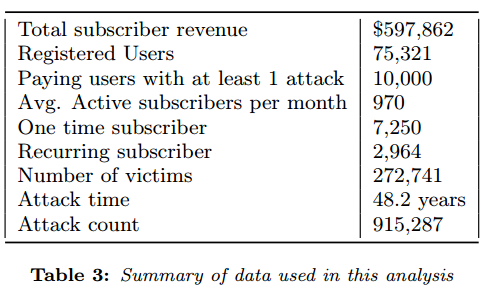

That initial vDOS story was based on data shared by an anonymous source who had hacked vDOS and obtained its private user and attack database. The story showed how the service made approximately $600,000 over just two of the four years it was in operation. Most of those profits came in the form of credit card payments via PayPal.

But prior to vDOS’s takedown in September 2016, the service was already under siege thanks to work done by a group of academic researchers who teamed up with PayPal to identify and close accounts that vDOS and other booter services were using to process customer payments. The researchers found that their interventions cut profits in half for the popular booter service, and helped reduce the number of attacks coming out of it by at least 40 percent.

At the height of vDOS’s profitability in mid-2015, the DDoS-for-hire service was earning its proprietors more than $42,000 a month in PayPal and Bitcoin payments from thousands of subscribers. That’s according to an analysis of the leaked vDOS database performed by researchers at New York University.

As detailed in August 2015’s “Stress-Testing the Booter Services, Financially,” the researchers posed as buyers of nearly two dozen booter services — including vDOS — in a bid to discover the PayPal accounts that booter services were using to accept payments. In response to their investigations, PayPal began seizing booter service PayPal accounts and balances, effectively launching their own preemptive denial-of-service attacks against the payment infrastructure for these services.

Those tactics worked, according to a paper the NYU researchers published today (PDF) at the Weis 2017 workshop at the University of California, San Diego.

“We find that VDoS’s revenue was increasing and peaked at over $42,000/month for the month before the start of PayPal’s payment intervention and then started declining to just over $20,000/month for the last full month of revenue,” the paper notes.

The NYU researchers found that vDOS had extremely low costs, and virtually all of its business was profit. Customers would pay up front for a subscription to the service, which was sold in booter packages priced from $5 to $300. The prices were based partly on the overall number of seconds that an attack may last (e.g., an hour would be 3,600 worth of attack seconds).

The NYU researchers found that vDOS had extremely low costs, and virtually all of its business was profit. Customers would pay up front for a subscription to the service, which was sold in booter packages priced from $5 to $300. The prices were based partly on the overall number of seconds that an attack may last (e.g., an hour would be 3,600 worth of attack seconds).

In just two of its four year in operation vDOS was responsible for launching 915,000 DDoS attacks, the paper notes. In adding up all the attack seconds from those 915,000 DDoS attacks, the researchers found vDOS was responsible for 48 “attack years” — the total amount of DDoS time faced by the victims of vDOS. Continue reading

Headquartered in San Francisco, OneLogin provides single sign-on and identity management for cloud-base applications. OneLogin counts among its customers some 2,000 companies in 44 countries, over 300 app vendors and more than 70 software-as-a-service providers.

Headquartered in San Francisco, OneLogin provides single sign-on and identity management for cloud-base applications. OneLogin counts among its customers some 2,000 companies in 44 countries, over 300 app vendors and more than 70 software-as-a-service providers.

In April 2017 I received an anonymous tip from a reader who said he’d figured out that just by changing a single number in the Web address when accessing his recent medical claim at MolinaHealthcare.com he could then view any and all other patient claims.

In April 2017 I received an anonymous tip from a reader who said he’d figured out that just by changing a single number in the Web address when accessing his recent medical claim at MolinaHealthcare.com he could then view any and all other patient claims.