Citing ongoing security concerns, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) has suspended a service offered via its Web site that allowed taxpayers to retrieve so-called IP Protection PINs (IP PINs), codes that the IRS has mailed to some 2.7 million taxpayers to help prevent those individuals from becoming victims of tax refund fraud two years in a row. The move comes just days after KrebsOnSecurity first exposed how ID thieves were abusing the service to revisit tax refund on innocent taxpayers two years running.

Last week, this blog told the story of Becky Wittrock, a certified public accountant (CPA) from Sioux Falls, S.D., who received an IP PIN in 2014 after crooks tried to impersonate her to the IRS. Wittrock said she found out her IP PIN had been compromised by thieves this year after she tried to file her tax return on Feb. 25, 2016. Turns out, the crooks beat her to the punch by more than three weeks, filing a large refund request with the IRS on Feb. 2, 2016.

Last week, this blog told the story of Becky Wittrock, a certified public accountant (CPA) from Sioux Falls, S.D., who received an IP PIN in 2014 after crooks tried to impersonate her to the IRS. Wittrock said she found out her IP PIN had been compromised by thieves this year after she tried to file her tax return on Feb. 25, 2016. Turns out, the crooks beat her to the punch by more than three weeks, filing a large refund request with the IRS on Feb. 2, 2016.

The problem, as Wittrock’s case made clear, is that IRS allows IP PIN recipients to retrieve their PIN via the agency’s Web site, after supplying the answers to four easy-to-guess questions from consumer credit bureau Equifax. These so-called knowledge-based authentication (KBA) or “out-of-wallet” questions focus on things such as previous address, loan amounts and dates and can be successfully enumerated with random guessing. In many cases, the answers can be found by consulting free online services, such as Zillow and Facebook.

In a statement issued Monday evening, the IRS said that as part of its ongoing security review, the agency was temporarily suspending the Identity Protection PIN tool on IRS.gov.

“The IRS is conducting a further review of the application that allows taxpayers to retrieve their IP PINs online and is looking at further strengthening the security features on the tool,” the agency said. Continue reading

As

As  The number is more than double the figures the IRS released in August 2015, when it said some

The number is more than double the figures the IRS released in August 2015, when it said some

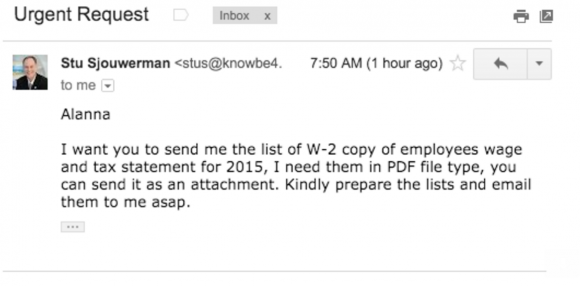

Stu Sjouwerman, chief executive at security awareness training company KnowBe4, told KrebsOnSecurity that earlier this week his firm’s controller received an email designed to look like it was sent by Sjouwerman requesting a copy of all employee W-2 forms for this year (full disclosure: KnowBe4 is an advertiser on this site). The email read:

Stu Sjouwerman, chief executive at security awareness training company KnowBe4, told KrebsOnSecurity that earlier this week his firm’s controller received an email designed to look like it was sent by Sjouwerman requesting a copy of all employee W-2 forms for this year (full disclosure: KnowBe4 is an advertiser on this site). The email read: