Phishers and phone fraudsters are capitalizing on public concern over a massive data breach announced this week at health insurance provider Anthem in a bid to steal financial and personal data from consumers.

The flood of phishing scams was unleashed just hours after Anthem announced publicly that a “very sophisticated cyberattack” on its systems had compromised the Social Security information and other personal details on some 80 million Americans.

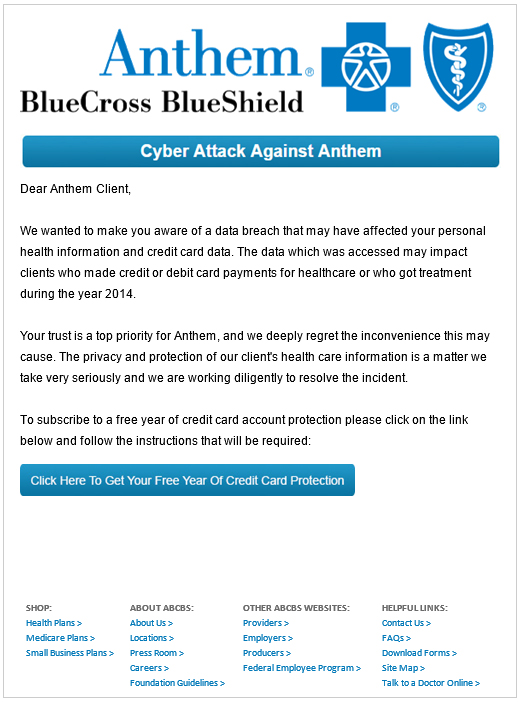

In a question on its FAQ page about whether it would be offering credit monitoring to affected customers, “Anthem said All impacted members will receive notice via mail which will advise them of the protections being offered to them as well as any next steps.” Unsurprisingly, phishers took that as an invitation to blast out variations on the scam pictured below, which spoofs Anthem and offers recipients a free year’s worth of credit monitoring services for those who click the embedded link.

According to Anthem, fraudsters also are busy perpetrating similar scams by cold-calling people via telephone. In a recording posted to its toll-free hotline for this breach (877-263-7995), Anthem said it is aware of outbound call scams targeting current and former Anthem members.

“These emails and calls are not from anthem and no notifications have been sent from anthem since the initial notification on Feb. 4, 2015,” Anthem said in a voice recording on the hotline.

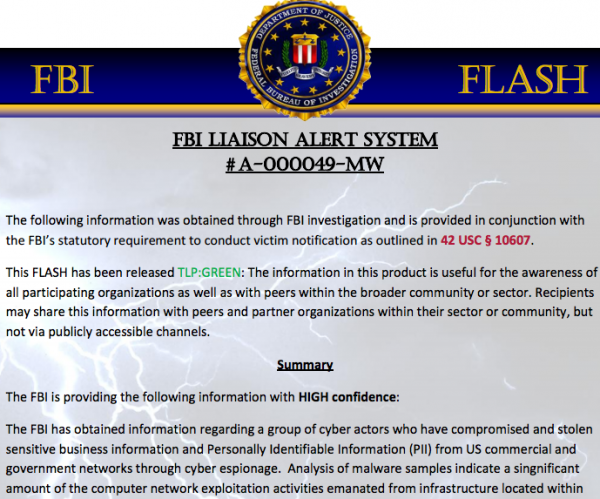

It is likely that these phishing and phone scams are random and opportunistic, but there is always the possibility that the data stolen from Anthem has fallen into the hands of scam artists. According to Anthem, the information stolen includes the consumer’s name, date of birth, member ID, street address, email address, phone number and employment information. However, experts believe that the attack on Anthem was perpetrated by state-sponsored hackers from China seeking information on specific individuals for espionage purposes, although that conclusion has not been independently confirmed.

The company says it will begin sending notifications to affected consumers via snail mail in the coming weeks. In the meantime, if you’re a current or former Anthem member, be aware that these types of scams are likely to escalate in the coming days and weeks.

Update, Feb. 9, 6:15 p.m. ET: In a somewhat farcical turn of events, it appears that the image above is actually from a phishing education campaign created by a company that helps firms impress upon their employees the importance of cybersecurity. The image above, when clicked, brings users to this page, which warns visitors they’ve clicked on a link design to test awareness. That page is run by Knowbe4, whose CEO Stu Sjouwerman said in response to an inquiry that the image was likely forwarded to Anthem by a cautious employee of one of Knowbe4’s customers who received the phishing test but did not click the link. Full disclosure: Knowbe4 is an advertiser on this blog.