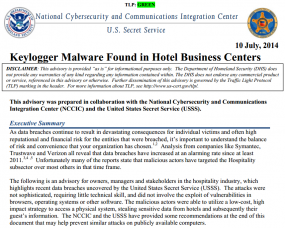

Three Israeli defense contractors responsible for building the “Iron Dome” missile shield currently protecting Israel from a barrage of rocket attacks were compromised by hackers and robbed of huge quantities of sensitive documents pertaining to the shield technology, KrebsOnSecurity has learned.

The never-before publicized intrusions, which occurred between 2011 and 2012, illustrate the continued challenges that defense contractors and other companies face in deterring organized cyber adversaries and preventing the theft of proprietary information.

According to Columbia, Md.-based threat intelligence firm Cyber Engineering Services Inc. (CyberESI), between Oct. 10, 2011 and August 13, 2012, attackers thought to be operating out of China hacked into the corporate networks of three top Israeli defense technology companies, including Elisra Group, Israel Aerospace Industries, and Rafael Advanced Defense Systems.

By tapping into the secret communications infrastructure set up by the hackers, CyberESI determined that the attackers exfiltrated large amounts of data from the three companies. Most of the information was intellectual property pertaining to Arrow III missiles, Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs), ballistic rockets, and other technical documents in the same fields of study.

Joseph Drissel, CyberESI’s founder and chief executive, said the nature of the exfiltrated data and the industry that these companies are involved in suggests that the Chinese hackers were looking for information related to Israel’s all-weather air defense system called Iron Dome.

The Israeli government has credited Iron Dome with intercepting approximately one-fifth of the more than 2,000 rockets that Palestinian militants have fired at Israel during the current conflict. The U.S. Congress is currently wrangling over legislation that would send more than $350 million to Israel to further development and deployment of the missile shield technology. If approved, that funding boost would make nearly $1 billion from the United States over five years for Iron Dome production, according to The Washington Post.

Neither Elisra nor Rafael responded to requests for comment about the apparent security breaches. A spokesperson for Israel Aerospace Industries brushed off CyberESI’s finding, calling it “old news.” When pressed to provide links to any media coverage of such a breach, IAI was unable to locate or point to specific stories. The company declined to say whether it had alerted any of its U.S. industry partners about the breach, and it refused to answer any direct questions regarding the incident.

“At the time, the issue was treated as required by the applicable rules and procedures,” IAI Spokeswoman Eliana Fishler wrote in an email to KrebsOnSecurity. “The information was reported to the appropriate authorities. IAI undertook corrective actions in order to prevent such incidents in the future.”

“At the time, the issue was treated as required by the applicable rules and procedures,” IAI Spokeswoman Eliana Fishler wrote in an email to KrebsOnSecurity. “The information was reported to the appropriate authorities. IAI undertook corrective actions in order to prevent such incidents in the future.”

Drissel said many of the documents that were stolen from the defense contractors are designated with markings indicating that their access and sharing is restricted by International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR) — U.S. State Department controls that regulate the defense industry. For example, Drissel said, among the data that hackers stole from IAI is a 900-page document that provides detailed schematics and specifications for the Arrow 3 missile.

“Most of the technology in the Arrow 3 wasn’t designed by Israel, but by Boeing and other U.S. defense contractors,” Drissel said. “We transferred this technology to them, and they coughed it all up. In the process, they essentially gave up a bunch of stuff that’s probably being used in our systems as well.”

WHAT WAS STOLEN, AND BY WHOM?

According to CyberESI, IAI was initially breached on April 16, 2012 by a series of specially crafted email phishing attacks. Drissel said the attacks bore all of the hallmarks of the “Comment Crew,” a prolific and state-sponsored hacking group associated with the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and credited with stealing terabytes of data from defense contractors and U.S. corporations.

The Comment Crew is the same hacking outfit profiled in a February 2013 report by Alexandria, Va. based incident response firm Mandiant, which referred to the group simply by it’s official designation — “P.L.A. Unit 61398.” In May 2014, the U.S. Justice Department charged five prominent military members of the Comment Crew with a raft of criminal hacking and espionage offenses against U.S. firms. Continue reading

![Indexeus[dot]org](https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/indexeus-285x176.png)