Ooh, you might not ever get rich

But let me tell ya, it’s better than diggin’ a ditch

“Car Wash” by Rose Royce

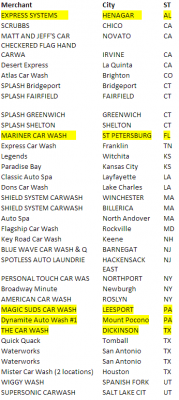

An investigation into a string of credit card breaches at dozens of car wash locations across the United States illustrates the challenges facing local law enforcement as they seek to connect the dots between cybercrime and local gang activity that increasingly cross multiple domestic and international borders.

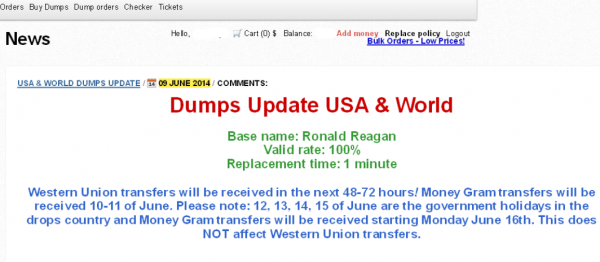

Earlier this month, police in Everett, Massachusetts arrested a local man named Jean Pierre for possessing nine stolen credit card accounts. The cards themselves weren’t stolen: They were gift cards that had been re-encoded with data from cards that were stolen from a variety of data breaches at merchants, including a Splash Car Wash in Connecticut.

Earlier this month, police in Everett, Massachusetts arrested a local man named Jean Pierre for possessing nine stolen credit card accounts. The cards themselves weren’t stolen: They were gift cards that had been re-encoded with data from cards that were stolen from a variety of data breaches at merchants, including a Splash Car Wash in Connecticut.

How authorities in Massachusetts connected Pierre to a cybercrime at a Connecticut car wash is a mix of odd luck and old-fashioned police work. In May, the Everett police department received a complaint from a sheriff’s department in South Carolina about a resident who’d had his credit card account used repeatedly for fraudulent transactions at a Family Dollar store in Everett.

Everett PD Detective Michael Lavey obtained security camera footage from the local Dollar Store in question. When Lavey asked the store clerk if he knew the individuals pictured at the date and time of the fraudulent transactions, the clerk said the suspects had been coming in for months — several times each week — always purchasing gift cards.

“The clerk told me they would come into the store in pairs, using multiple credit cards until one of them was finally approved, at which point they’d buy $500 each in prepaid gift cards,” Lavey said. “We have two Family Dollar stores in Everett and a bunch in the surrounding area, and these guys would come in three to four times a week at each location, laundering money from stolen cards.”

Not long after Lavey posted snapshots from the video footage on a state-wide police network, he heard from an officer in Boston who said a suspect resembling one of the men in the photos was recently questioned at a city hospital after being stabbed in the legs and buttocks in an unrelated robbery. The assailant in that attack was arrested, but his victim — Jean Pierre — refused to answer questions about the incident. The police seized Jean Pierre’s pants as evidence in the assault case, and discovered numerous prepaid cards in the pockets of the trousers.

Lavey said he subpoenaed the credit card records, and working with investigators at American Express and Citibank was able to determine that at least one of the cards had been stolen from the Splash Car Wash in Connecticut. In effect, thieves were buying stolen cards to finance the purchase of gift cards, some of which would later serve as hosts for new stolen card data once their balance was exhausted. The cops call it money laundering, but in this case it might as well be called card washing.

WILL THAT BE A SUPER OR DELUXE WASH?

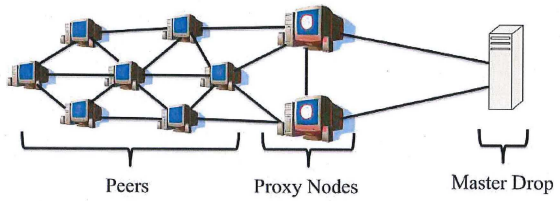

Soon enough, Lavey had linked up with Michael Chaves, a detective with the police department in Monroe, Conn. who’d been investigating card breaches at 14 separate car washes in his state, including the Splash case. Working with the Connecticut Financial Crimes Task Force, a broad law enforcement group that includes the U.S. Secret Service and state police, they determined that the local company was but one of at least 40 car washes across the country that had been hacked and relieved of countless customer credit and debit cards since at least February 2014.

Chaves said he interviewed several of the car wash owners, and discovered that they were all using the same point-of-sale systems developed by Randolph, N.J.-based Micrologic Associates. Chaves said the store owners told him the devices had remote access via Symantec’s pcAnywhere enabled, access that was granted to anyone who knew the same set of default credentials.

“The pcAnywhere credentials were created by Micrologic, but unchanged for years,” Chaves said.

That was the same conclusion independently reached by Detective Steven LaMears with the police department in Keene, N.H. Earlier this month, a police captain at the Keene Police Dept. saw fraudulent charges show up on his credit card shortly after using it at the town’s Key Road Car Wash, an establishment which used Micrologic’s point-of-sale system.

LaMears also heard from a company in New York which reported that two its executives each had their cards compromised multiple times after visiting the Key Road Car Wash in Keene.

“We confronted them, and working with the U.S. Secret Service got them back up and running,” LaMears said of the local compromised car wash. “The Secret Service told us they were running an old version of Micrologic that had the same, one login for everything, and were using an old version of Windows XP.” Continue reading