A 2011 hacker break-in at banking industry behemoth Fidelity National Information Services (FIS) was far more extensive and serious than the company disclosed in public reports, banking regulators warned FIS customers last month. The disclosure highlights a shocking lack of basic security protections throughout one of the nation’s largest financial services providers.

Jacksonville, Fla. based FIS is one of the largest information processors for the banking industry today, handling a range of services from check and credit card processing to core banking functions for more than 14,000 financial institutions in over 100 countries.

Jacksonville, Fla. based FIS is one of the largest information processors for the banking industry today, handling a range of services from check and credit card processing to core banking functions for more than 14,000 financial institutions in over 100 countries.

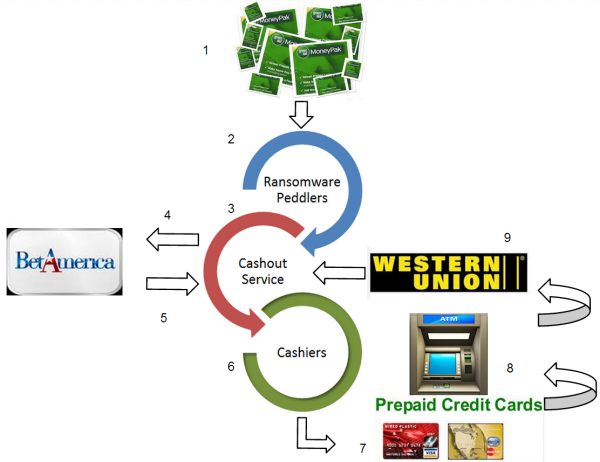

The company came under heavy scrutiny from banking industry regulators in the first quarter of 2011, when hackers who had broken into its networks used that access to orchestrate a carefully-timed, multi-million dollar ATM heist. In that attack, the hackers raised or eliminated the daily withdrawal limits for 22 debit cards they’d obtained from FIS’s prepaid card network. The fraudsters then cloned the cards and distributed them to co-conspirators who used them to pull $13 million in cash from FIS via ATMs in several major cities across Europe, Russia and Ukraine.

FIS first publicly reported broad outlines of the breach in a May 3, 2011 filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), stating that it had identified “7,170 prepaid accounts may have been at risk and that three individual cardholders’ non-public information may have been disclosed as a result of the unauthorized activities.” FIS told the SEC it worked with the impacted clients to take appropriate action, including blocking and reissuing cards for the affected accounts. “The Company has taken steps to further enhance security and continues to work with Federal law enforcement officials on this matter,” it declared in its filing.

FIS’s disclosure to investors cast the breach as limited in scope, saying the break-in was restricted to unauthorized activity at a portion of its network belonging to a small prepaid debit card provider that it acquired in 2007. But bank examiners at the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. (FDIC) who audited FIS’s operations in the months following the 2011 breach and again in October 2012 came to a very different conclusion: According to a report that the FDIC sent May 24, 2013 to hundreds of FIS’s customer banks and obtained by KrebsOnSecurity, the 2011 breach was much larger than previously reported.

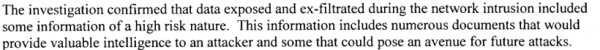

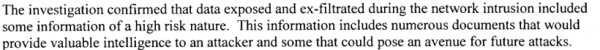

“The initial findings have identified many additional servers exposed by the attackers; and many more instances of the malware exploits utilized in the network intrusions of 2011, which were never properly identified or assessed,” the FDIC examiners wrote in a report from October 2012. “As a result, FIS management now recognizes that the security breach events of 2011 were not just a pre-paid card fraud event, as originally maintained, but rather are that of a broader network intrusion.”

Indeed, the FDIC’s examiners found that there was scarcely a portion of the FIS network that the hackers did not touch.

“From review of the previous investigation reports, along with other documentation provided by FIS, examiners and payment card industry experts identified over 2,000 touch points that indicated a broad exposure of internal FIS systems and client related data,” the report notes. “These systems include, but are not limited to, the The New York Currency Exchange ATM network, prime core application systems, and various Internet banking, ACH, and wire transfer systems. These touch points also indicated approximately 100 client financial institutions, which appear to have had sensitive data exposed by the attackers.”

A screen shot of an excerpt from the FDIC report on security lapses at FIS.

In an emailed statement, FIS maintained that “no client of FIS suffered any monetary loss as a result of the incident, and stressed that the report is based upon a review that was completed in October 2012.

“Since that time, FIS has continued to strengthen its information security and risk position, including investments over two years of $100 million or more, as part of our goal to provide best-in-class information security and risk management to each of our 14,000-plus clients. We have openly and regularly communicated these initiatives, our progress and results to our clients and shareholders through meetings, monthly updates, quarterly public disclosures, Board materials, educational webinars, and more.”

WHAT DOES $100 MILLION BUY?

Nevertheless, investors may be less than pleased about how FIS is spending its security dollars. The FDIC found that even though FIS has hired a number of incident response firms and has spent more than $100 million responding to the 2011 breach, the company failed to enact some very basic security mechanisms. For example, the FDIC noted that FIS routinely uses blank or default passwords on numerous production systems and network devices, even though these were some of the same weaknesses that “contributed to the speed and ease with which attackers transgressed and exposed FIS systems during the 2011 network intrusion.”

“Many FIS systems remain configured with default passwords, no passwords, non-complex passwords, and non-expiring passwords,” the FDIC wrote. “Enterprise vulnerability scans in November 2012, noted over 10,000 instances of default passwords in use within the FIS environment.”

The bank auditors also found “a high number of unresolved network and application vulnerabilities remain throughout the enterprise.

“The Executive Summary Scan reports from November 2012 show 18,747 network vulnerabilities and over 291 application vulnerabilities as past due,” the report charges.

What’s more, investigators probing the breach at FIS may have been denied key clues about the source of the intrusion because FIS incident response personnel wiped many of the compromised systems and put them back on the network before the machines could be properly examined.

“Many systems were re-constituted and introduced back into the production environment before data preservation techniques were applied,” the report notes. “Additionally, poor forensic preservation techniques led to numerous servers being re-imaged before analysis was completed and significant logging data was inadvertently destroyed. Several servers, key to the investigation process, were re-introduced into the production environment and subsequently re-compromised due to misconfigured baselines and inadequate security testing outside of corporate policy.”

Continue reading →