The U.S. Department of Homeland Security is warning that a group of mostly Middle East- and North Africa-based criminal hackers are preparing to launch a cyber attack campaign next week known as “OpUSA” against websites of high-profile US government agencies, financial institutions, and commercial entities. But security experts remain undecided on whether this latest round of promised attacks will amount to anything more than a public nuisance.

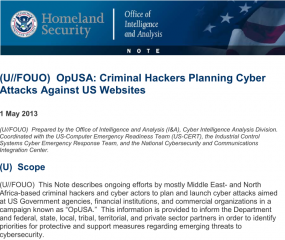

A confidential alert, produced by DHS on May 1 and obtained by KrebsOnSecurity, predicts that the attacks “likely will result in limited disruptions and mostly consist of nuisance-level attacks against publicly accessible webpages and possibly data exploitation. Independent of the success of the attacks, the criminal hackers likely will leverage press coverage and social media to propagate an anti-US message.”

A confidential alert, produced by DHS on May 1 and obtained by KrebsOnSecurity, predicts that the attacks “likely will result in limited disruptions and mostly consist of nuisance-level attacks against publicly accessible webpages and possibly data exploitation. Independent of the success of the attacks, the criminal hackers likely will leverage press coverage and social media to propagate an anti-US message.”

The DHS alert is in response to chest-thumping declarations from anonymous hackers who have promised to team up and launch a volley of online attacks against a range of U.S. targets beginning May 7. “Anonymous will make sure that’s this May 7th will be a day to remember,” reads a rambling, profane manifesto posted Apr. 21 to Pastebin by a group calling itself N4M3LE55 CR3W.

“On that day anonymous will start phase one of operation USA. America you have committed multiple war crimes in Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and recently you have committed war crimes in your own country,” the hackers wrote. “We will now wipe you off the cyber map. Do not take this as a warning. You can not stop the internet hate machine from doxes, DNS attacks, defaces, redirects, ddos attacks, database leaks, and admin take overs.”

Ronen Kenig, director of security solutions at Tel Aviv-based network security firm Radware, said the impact of the attack campaign will be entirely dependent on which hacking groups join the fray. He noted that a recent campaign called “OpIsrael” that similarly promised to wipe Israel off the cyber map fizzled spectacularly.

“There were some Web site defacements, but OpIsrael was not successful from the attackers point-of-view,” Kenig said. “The main reason was the fact that the groups that initiated the attack were not able to recruit a massive botnet. Lacking that, they depended on human supporters, and those attacks from individuals were not very massive.”

But Rodney Joffe, senior vice president at Sterling, Va. based security and intelligence firm Neustar, said all bets are off if the campaign is joined by the likes of the Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Cyber Fighters, a hacker group that has been disrupting consumer-facing Web sites for U.S. financial institutions since last fall. The hacker group has said its attacks will continue until copies of the controversial film Innocence of Muslims movie are removed from Youtube.

But Rodney Joffe, senior vice president at Sterling, Va. based security and intelligence firm Neustar, said all bets are off if the campaign is joined by the likes of the Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Cyber Fighters, a hacker group that has been disrupting consumer-facing Web sites for U.S. financial institutions since last fall. The hacker group has said its attacks will continue until copies of the controversial film Innocence of Muslims movie are removed from Youtube.

Joffe said it’s easy to dismiss a hacker manifesto full of swear words and leetspeak as the ramblings of script kiddies and impressionable, wannabe hackers who are just begging for attention. But when that talk is backed by real firepower, the attacks tend to speak for themselves.

“I think we learned our lesson with the al-Qassam Cyber Fighters,” Joffe said. “The damage they’re capable of doing may be out of proportion with their skills, but that’s been going on for seven months and it’s been brutally damaging.”

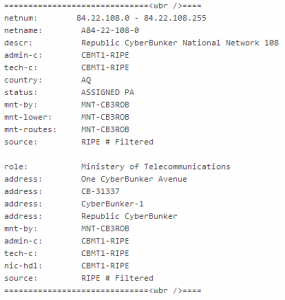

According to the DHS alert, 46 U.S. financial institutions have been targeted with DDoS attacks since September 2012 — with various degrees of impact — in over 200 separate DDoS attacks.

“These attacks have utilized high bandwidth webservers with vulnerable content management systems,” the agency alert states. “Typically a customer account is compromised and attack scripts are then uploaded to a hidden directory on the customer website. To date the botnets have been identified as ‘Brobot’ and ‘Kamikaze/Toxin.’”

In an interview with Softpedia, representatives of Izz ad-Din al-Qassam said they do indeed plan to lend their firepower to the OpUSA attack campaign.

![After migrating the data from Exposed.su to Exposed.re, the curator added [Swatted] notations.](https://krebsonsecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/04/Fotor0417131216-600x450.jpg)