“History is much decried; it is a tissue of errors, we are told, no doubt correctly; and rival historians expose each other’s blunders with gratification. Yet the worst historian has a clearer view of the period he studies than the best of us can hope to form of that in which we live. The obscurest epoch is to-day; and that for a thousand reasons of incohate tendency, conflicting report, and sheer mass and multiplicity of experience; but chiefly, perhaps, by reason of an insidious shifting of landmarks.” – Robert Louis Stevenson

To say that there is a law enforcement manhunt on for the individuals responsible for posting credit report information on public figures and celebrities at the rogue site exposed.su would be a major understatement. I like to think that when that investigation is completed, some of the information I’ve helped to uncover about those affiliated with the site will come to light. For now, however, I’m content to retrace some of my footwork this past weekend that went into tracking individuals who may have been responsible for attacking my site and SWATing my home last Thursday.

I state upfront that the information in this piece is certainly not the whole story (most news reporting is, at best, a snapshot in time, a first rough draft of history). While the clues I’ve uncovered thus far point to the role of a single individual, this person is likely part of a larger group involved in hacking and SWATing activity.

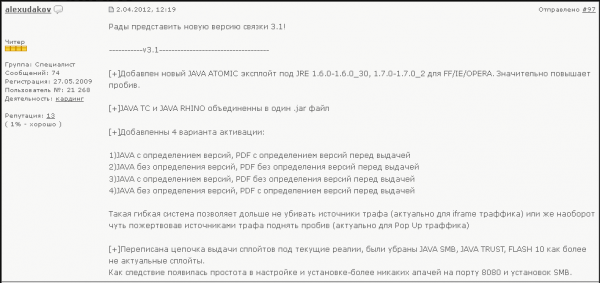

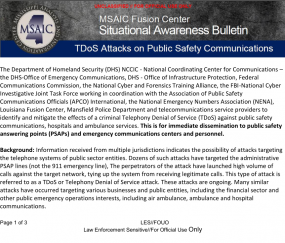

In my story last week, I posted a copy of the internal database for booter.tw, one of several fee-for-service “booter” sites. Booter sites are perhaps most popular among online gaming enthusiasts, who like to use them to knock opponents offline; but they are frequently also used to launch debilitating attacks on Web sites. That leaked booter.tw database shows that the denial-of-service attack that hit my site last week was paid for by a booter.tw user with the account name “countonme,” and using the address “countonme@gmail.com.”

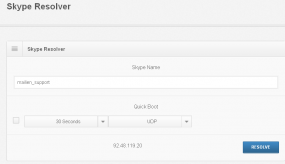

Since the attack, I reached out to the proprietor of booter.tw, a hacker who uses the nickname “Askaa.” He informed me that the individual who launched the attack on my site was a hacker who used the screen name Phobia. “Phobia hacked into the countonme account to make it look like the according user attacked you,” Askaa said in a brief interview over Skype instant message. Askaa declined to say why he was so confident of this information.

RealTeamHype’s Youtube page before the videos were deleted on Sunday.

Separately, over the weekend I received an email from a person who claimed to have direct knowledge of the attacks (perhaps because he, too, was involved). This individual said those who attacked my site were a group of young online video game enthusiasts who were upset that earlier in the week I’d written about ssndob.ru, a site that sells access to peoples’ credit files, Social Security numbers and other sensitive information.

According to this source, the hackers in this case belong to a four-man Xbox live gamer team that calls itself “Team Hype,” which until this past weekend had posted a number of videos to their own youtube.com channel, RealTeamHype (more on what happened to these videos in a moment).

According to the anonymous source, Team Hype consists of hackers who use the nicknames “Trojan,” “Shadow,” Convict,” and “Phobia.” The source said the group used SSNs from ssndob.ru to hijack “gamertags,” online personas tied to Xbox Live game accounts. In this case, specifically from Microsoft employees who work on the Xbox Live gaming platform. Some of the group members then sell those accounts to other Xbox Live players.

“They hack/social engineer Gamertags off Microsoft employees by using SSNs,” the source wrote. “I didn’t DDoS your site and I didn’t SWAT you, Phobia has been telling everyone he did. The method he released he said he gets SSNs, then calls phone companies and redirects the number and than gets xbox phone support to call number and confirm. I heard he got pissed that you released the site he uses. Also Trojan told a buddie of mines ‘fear'(on AIM) something about a dead body in your closet about your swat.”

Snippet from @PhobiaTheGod’s now-closed Twitter account

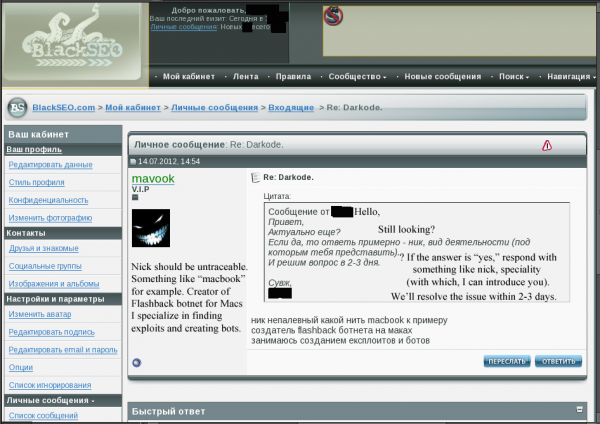

The source said Phobia used the Twitter account @PhobiaTheGod (now closed, but partially available here and at this cache), and that Phobia’s personal information — including real name, address and phone number — had been “doxed” or released onto Pastebin-like sites some time ago. It didn’t take long to locate this profile at skidpaste.org (“skid” is a diminutive reference to the term “script kiddies,” referring to relatively unskilled young hackers who conduct most of their exploits using automated tools without understanding how those tools actually do the dirty work).

Having watched most of the videos at RealTeamHype’s youtube channel, it appeared that my source was telling the truth about the hijacked accounts: In fact, the videos at that channel documented such hijackings in progress using desktop screen-grabbing software. The videos even showed conversations with other team members in instant message windows in the background.

But I was reluctant to put much stock in the information until the source sent me a piece of information that only the attackers and my ISP would have known. On Friday, I received a call from Cox Communications, my Internet service provider. They wanted to know why I had paid $3,000 toward my account using several different credit card numbers. I assured them that I hadn’t made that payment. Then I heard from a member of Cox’s security team, who asked if I’d reset my password and if I’d indeed asked to cancel my Internet service. He was unsurprised to learn that I hadn’t. Apparently, hackers reset the password to my Cox email account by working out the answer to my secret question (this account is separate from my Cox user account, was set up over 10 years ago, and has never been used for anything remotely interesting or sensitive).

The source told me via email: “Hey brian, i just spoke to fear he told me phobia and his buddies were telling him that they hacked your cox email and paid your cox bill with hacked credit card, im not sure if this is true but im letting you know.”

I decided to give a call to the phone number included in the doxed records for Phobia, which rang at a home in Milford, Ct. A 20-year-old named Ryan Stevenson picked up the phone. After introducing myself, I asked Ryan if he knew anything about booter.tw, and he said he didn’t bother with booter sites because they were lame.

Continue reading →

On Sept. 1, 2010, unidentified computer crooks began making unauthorized wire transfers out of the bank accounts belonging to Oregon Hay Products Inc., a hay compressing facility in Boardman, Oregon. In all, the thieves stole $223,500 in three wire transfers of just under $75,000 over a three day period.

On Sept. 1, 2010, unidentified computer crooks began making unauthorized wire transfers out of the bank accounts belonging to Oregon Hay Products Inc., a hay compressing facility in Boardman, Oregon. In all, the thieves stole $223,500 in three wire transfers of just under $75,000 over a three day period.