It’s not often that one has the opportunity to be the target of a cyber and kinetic attack at the same time. But that is exactly what’s happened to me and my Web site over the past 24 hours. On Thursday afternoon, my site was the target of a fairly massive denial of service attack. That attack was punctuated by a visit from a heavily armed local police unit that was tricked into responding to a 911 call spoofed to look like it came from my home.

Well, as one gamer enthusiast who follows me on Twitter remarked, I guess I’ve now “unlocked that level.”

Things began to get interesting early Thursday afternoon, when a technician from Prolexic, a company which protects Web sites (including KrebsOnSecurity.com) from denial-of-service attacks, forwarded a strange letter they’d received earlier in the day that appeared to have been sent from the FBI. The letter, a copy of which is reprinted in its entirety here, falsely stated that my site was hosting illegal content, profiting from cybercriminal activity, and that it should be shut down. Prolexic considered it a hoax, but forwarded it anyway. I similarly had no doubt it was a fake, and a short phone call to the FBI confirmed that fact.

Around the same time, my site came under a series of denial-of-service attacks, briefly knocking it offline. While Prolexic technicians worked to filter the attack traffic, I got busy tidying up the house (since we were expecting company for dinner). I heard the phone ring up in the office while I was downstairs vacuuming the living room and made a mental note to check my voicemail later. Vacuuming the rug near the front door, I noticed that some clear plastic tape I’d used to secure an extension cord for some outdoor lights was still straddling the threshold of the front door.

When I opened the door to peel the rest of the tape off, I heard someone yell, “Don’t move! Put your hands in the air.” Glancing up from my squat, I saw a Fairfax County Police officer leaning over the trunk of a squad car, both arms extended and pointing a handgun at me. As I very slowly turned my head to the left, I observed about a half-dozen other squad cars, lights flashing, and more officers pointing firearms in my direction, including a shotgun and a semi-automatic rifle. I was instructed to face the house, back down my front steps and walk backwards into the adjoining parking area, after which point I was handcuffed and walked up to the top of the street.

I informed the responding officers that this was a hoax, and that I’d even warned them in advance of this possibility. In August 2012, I filed a report with Fairfax County Police after receiving non-specific threats. The threats came directly after I wrote about a service called absoboot.com, which is a service that can be hired to knock Web sites offline.

One of the reasons that I opted to file the report was because I knew some of the young hackers who frequented the forum on which this service was advertised had discussed SWATting someone as a way of exacting revenge or merely having fun at the target’s expense. To my surprise, the officer who took my report said he had never heard of the phenomenon, but promised to read up on it.

One of the officers asked if it was okay to enter my house, and I said sure. Then an officer who was dressed more like a supervisor approached me and asked if I was the guy who had filed a police report about this eventuality about six months earlier. When I responded in the affirmative, he spoke into his handheld radio, and the police began stowing their rifles and the cuffs were removed from my wrists. He explained that they’d tried to call me on the phone number that had called them (my mobile), but that there was no answer. He apologized for the inconvenience, and said they were only doing their jobs. I told him no hard feelings. He told me that the problem of SWATting started on the West Coast and has been slowly making its way east.

The cop that took the report from me after the incident said someone had called 911 using a Caller ID number that matched my mobile phone number; the caller claimed to be me, reporting that Russians had broken into the home and shot my wife. Obviously, this was not the case, and nobody was harmed during the SWATing.

Update, Apr. 29, 2013: As I noted halfway through this follow-up post, the police officer was misinformed: The 911 call was actually made via instant message chats using a relay service designed for hearing impaired and deaf callers, *not* via a spoofed mobile phone call.

Original story:

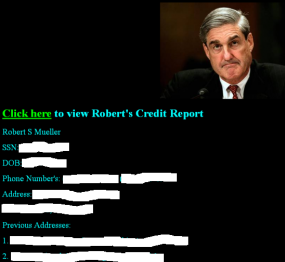

It’s difficult to believe the phony FBI letter that Prolexic received, the denial-of-service attack, and the SWATting were somehow the work of different individuals upset over something I’ve written. The letter to Prolexic made no fewer than five references to a story I published earlier this week about sssdob.ru, a site advertised in the cybercrime underground that sells access to Social Security numbers and credit reports. That story was prompted by news media attention to exposed.su, a site that has been posting what appear to be Social Security numbers, previous addresses and other information on highly public figures, including First Lady Michelle Obama and the director of the FBI.