Over the past 18 months, I’ve published a series of posts that provide clues about the possible real-life identities of the men responsible for building some of the largest and most disruptive spam botnets on the planet. I’ve since done a bit more digging into the backgrounds of the individuals thought to be responsible for the Rustock and Waledac spam botnets, which has produced some additional fascinating and corroborating details about these two characters.

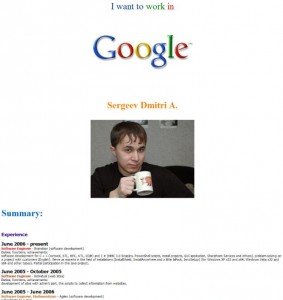

In March 2011, KrebsOnSecurity featured never-before-published details about the financial accounts and nicknames used by the Rustock botmaster. That story was based on information leaked from SpamIt, a cybercrime business that paid spammers to promote rogue Internet pharmacies (think Viagra spam). In a follow-up post, I wrote that the Rustock botmaster’s personal email account was tied to a domain name ger-mes.ru, which at one time featured a résumé of a young man named Dmitri A. Sergeev.

In March 2011, KrebsOnSecurity featured never-before-published details about the financial accounts and nicknames used by the Rustock botmaster. That story was based on information leaked from SpamIt, a cybercrime business that paid spammers to promote rogue Internet pharmacies (think Viagra spam). In a follow-up post, I wrote that the Rustock botmaster’s personal email account was tied to a domain name ger-mes.ru, which at one time featured a résumé of a young man named Dmitri A. Sergeev.

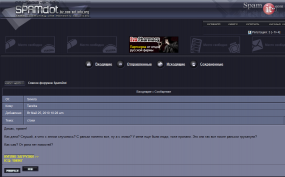

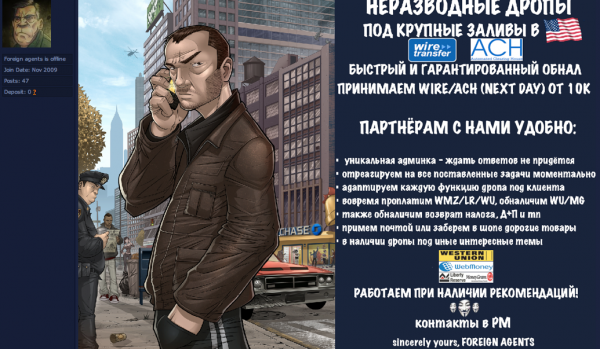

Then, on Jan. 26. 2012, I ran a story featuring a trail of evidence suggesting a possible identity of “Severa“ (a.k.a. “Peter Severa”), another SpamIt affiliate who is widely considered the author of the Waledac botnet (and likely the Storm Worm). In that story, I included several screen shots of Severa chatting on Spamdot.biz, an extremely secretive Russian forum dedicated to those involved in the spam business. In one of the screen shots, Severa laments the arrest of Alan Ralsky, a convicted American spam kingpin who specialized in stock spam and who — according to the U.S. Justice Department – was partnered with Severa. Anti-spam activists at Spamhaus.org maintain that Peter Severa’s real name is Peter Levashov (although the evidence I gathered also turned up another name, Viktor Sergeevich Ivashov).

It looks now like Spamhaus’s conclusion on Severa was closer to the truth. More on that in a second. I was able to feature the Spamdot discussions because I’d obtained a backup copy of the forum. But somehow in all of my earlier investigations I overlooked a handful of private messages between Severa and the Rustock botmaster, who used the nickname “Tarelka” on Spamdot. Apparently, the two worked together on the same kind of pump-and-dump stock spam schemes, but also knew each other intimately enough to be on a first-name basis.

The following is from a series of private Spamdot message exchanged between Tarelka and Severa on May 25 and May 26, 2010. In it, Severa refers to Tarelka as “Dimas,” a familiar form of “Dmitri.” Likewise, Tarelka addresses Severa as “Petka,” a common Russian diminutive of “Peter.” They discuss a mysterious mutual friend named John, who apparently used the nickname “Apple.”