An earlier version of this blog post incorrectly stated that Oracle had shipped security updates for its Java software. Oracle did push out an update for Java earlier this month — Java 6 Update 32 — but the new version was a maintenance update that did not include security fixes. My apologies for any confusion this may have caused.

Skimtacular: All-in-One ATM Skimmer

I spent the past week vacationing (mostly) in Southern California, traveling from Los Angeles to Santa Barbara and on to the wine country in Santa Ynez. Along the way, I received some information from a law enforcement source in the area about a recent ATM skimmer attack that showcased a well-designed and stealthy all-in-one skimmer.

The skimmer pictured below is the backside of a card acceptance slot overlay. It was recovered by a customer at a bank in the San Fernando Valley who called the cops upon her discovery. Police in the region still have no leads on who might have placed the device. The numeral “5” engraved in the upper right portion of this skimmer suggests that it was one in a series of fraud devices produced by this skimmer maker.

Help Kickstart a Film on Cybercrime

A deep sense of doubt and dread began to sink in halfway through our journey down a long, lonely desert highway from just outside Austin to coastal Texas. We were racing against the clock (we’d just scarfed down our third meal in a row at a roadside Subway shop), yet my minivan companions — a filmmaker from California and a husband-and-wife camera crew — seemed pleased with the footage we’d collected so far. I was far less sanguine about our prospects, and was almost certain that our carefully-laid plans to ambush a money mule on camera were about to unravel.

The scheme was hatched by Berkeley writer/director Charles Koppelman, who’d emailed me in mid-2011 about the possibility of catching some money mules on camera for a documentary he’s working on called Zero Day. Koppelman said the money shot would be a mule coming out of a bank with a wad of cash in hand, but that he’d settle for an old-fashioned sit-down interview.

At the time, I was working with a source who was injected into the communications networks of several money mule recruitment gangs. These miscreants specialize in hiring willing and unwitting “mules” through work-at-home job scams. The mules then are asked to process bank transfers that help organized cyber thieves launder money stolen from small businesses victimized by cybercrime. The networks my source was monitoring indicated the gang was grooming between 75 and 100 mules across the country on any given day, and that they were sending fraudulent transfers to mules almost daily.

I told Charles that for such a plan to work, we’d need to focus on areas that typically held the most number of mules per capita, and that meant somewhere in Florida or Texas. When my source indexed the mules and sorted them by hometown, we discovered that there were five mules being groomed for payments within about 200 miles of Austin, Texas. If we rented a car and checked in with my source on a regular basis, we might be able to secure the footage he was after, I suggested.

But I cautioned Koppelman that I gave our plan about a 20 percent chance of working. I predicted that most of the mules would quit, screw up the transfer task, or be used and discarded by the time we flew down there and actually hit the road. Indeed, when we reached our fleabag motel just south of Austin on Aug. 3, 2011, my prognostication had almost come true entirely: We were down to one last money mule: Geridana, a young, unemployed single mother of two from Webster, a small town of about 9,000 residents in southeastern Texas.

On the morning of Aug. 4, we piled into the minivan again and raced down to Webster. We didn’t attempt to make contact with her until we were parked outside of her apartment complex, which was next door to a bail bonds shop. Turns out that Geridana was a bit of an oddity: The $9,000+ the thieves had just sent her was actually the fourth such transfer that Geridana had processed in as many weeks. The most pathetic aspect of the whole scheme? She never got paid her promised monthly salary or per-task commissions.

I’ll stop the story here, because I don’t want to spoil the movie. That is, if it ever attracts enough funding to be finished. The film is co-financed by BBC Storyville, but Koppelman and his son Walker just launched a Kickstarter campaign to raise $20,000 to ensure continued filming of the project. A short introduction to their effort (including a scene starring Yours Truly) is available in the teaser video clip below. The filmmakers are also working with New York Times reporter John Markoff, Reuters reporter Joe Menn, and author Misha Glenny.

Microsoft Responds to Critics Over Botnet Bruhaha

Microsoft’s most recent anti-botnet campaign — a legal sneak attack against dozens of ZeuS botnets — seems to have ruffled the feathers of many in security community. The chief criticism is that the Microsoft operation exposed sensitive information that a handful of researchers had shared in confidence, and that countless law enforcement investigations may have been delayed or derailed as a result. In this post, I interview a key Microsoft attorney about these allegations.

Since Microsoft announced Operation B71, I’ve heard from several researchers who said they were furious at the company for publishing data on a group of hackers thought to be behind a majority of the ZeuS botnet activity — specifically those targeting small to mid-sized organizations that are getting robbed via cyber heists. The researchers told me privately that they believed Microsoft had overstepped its bounds with this action, using privileged information without permission from the source(s) of that data (many exclusive industry discussion lists dedicated to tracking cybercriminal activity have strict rules about sourcing and using information shared by other members).

Since Microsoft announced Operation B71, I’ve heard from several researchers who said they were furious at the company for publishing data on a group of hackers thought to be behind a majority of the ZeuS botnet activity — specifically those targeting small to mid-sized organizations that are getting robbed via cyber heists. The researchers told me privately that they believed Microsoft had overstepped its bounds with this action, using privileged information without permission from the source(s) of that data (many exclusive industry discussion lists dedicated to tracking cybercriminal activity have strict rules about sourcing and using information shared by other members).

At the time, nobody I’d heard from with complaints about the action wanted to speak on the record. Then, late last week, Fox IT, a Dutch security firm, published a lengthy blog post blasting Microsoft’s actions as “irresponsible,” and accusing the company of putting its desire for a public relations campaign ahead of its relationship with the security industry.

“This irresponsible action by Microsoft has led to hampering and even compromising a number of large international investigations in the US, Europe and Asia that we knew of and also helped with,” wrote Michael Sandee, Principal Security Expert at Fox IT. “It has also damaged and will continue to damage international relationships between public parties and also private parties. It also sets back cooperation between public and private parties, so called public private partnerships, as sharing will stop or will be definitely less valuable than it used to be for all parties involved.”

Sandee said that a large part of the information that Microsoft published about the miscreants involved was sourced from individuals and organizations without their consent, breaking various non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) and unspoken rules.

“In light of the whole Responsible Disclosure debate [link added] from the end of Microsoft this unauthorized and uncoordinated use and publication of information protected under an NDA is obviously troublesome and shows how Microsoft only cares about protecting their own interests,” Sandee wrote.

Given the strong feelings that Microsoft’s actions have engendered in the Fox IT folks and among the larger security community, I reached out to Richard Boscovich, a former U.S. Justice Department lawyer who was one of the key architects of Microsoft’s legal initiative against ZeuS. One complaint I heard from several researchers who believed that Microsoft used and published data they uncovered was that the company kept the operation from nearly everyone. I asked Boscovich how this operation was different from previous actions against botnets such as Rustock and Waledac.

Boscovich: It’s essentially the same approach we’ve done in all the other operations. The problem that I think some people have is that due to the type of operation, we can’t have the entire community involved. That’s for several reasons. One is operational security. The bigger the number of people involved, the more likely is that is someone will make a mistake and say something that could jeopardize all of the work that everyone has done. Also, we’re making representations to a federal court that this is an ex-parte motion and very limited people know about it. If you have multiple people knowing, and the entire security community knows, let’s say we submit declarations from 30-40 people. A court may say, ‘Well there’s a lot of people here who know about this, so isn’t this information that’s already publicly available? Don’t these people know you’re looking at them already?’ We’re really asking for an extraordinary remedy: an ex-parte TRO [temporary restraining order] is a very high standard. We have to show an immediate threat and harm, ongoing, so much so that we can’t even give the other side notice that we’re going to sue them and take away their property.

The other concern is more operational. When I was in the Justice Department — I was there for just shy of 18 years — we even compartmentalized operations there. Information was shared on a need-to-know basis, to make sure the operation would be a success and that there wouldn’t be any inadvertent leaks. It wasn’t because we didn’t trust people, but because people sometimes make mistakes. So in this operation, just like the others, we engaged with industry partners, academic partners, and some of those who wished to be open, and others who preferred to do things behind the scenes.

Thieves Replacing Money Mules With Prepaid Cards?

Recent ebanking heists — such as a $121,000 online robbery at a New York fuel supplier last month — suggest that cyber thieves increasingly are cashing out by sending victim funds to prepaid debit card accounts. The shift appears to be an effort to route around a major bottleneck for these crimes: Their dependency on unreliable money mules.

Mules traditionally have played a key role in helping thieves cash out hacked accounts and launder money. They are recruited through email-based work-at-home job scams, and are told they will be helping companies process payments. In a typical scheme, the mule provides her banking details to the recruiter, who eventually sends a fraudulent transfer and tells the mule to withdraw the funds in cash, keep a small percentage, and wire the remainder to co-conspirators abroad.

But mules are hardly the most expedient method of extracting funds. To avoid arousing suspicion (and triggering anti-money laundering reporting requirements by the banks), cyber crooks usually send less than $10,000 to each mule. In other words, for every $100,000 that the thieves want to steal, they need to have at least 10 money mules at the ready.

In reality, though, that number is quite often closer to 15 mules per $100,000. That’s because the thieves may send much lower amounts to mules that bank at institutions which have low transfer limit triggers. For instance, they almost always limit transfers to less than $5,000 when dealing with Bank of America mules, because they know transfers for more than that amount to consumer accounts will raise fraud flags at BofA.

Thus, the average mule is worth up to $10,000 to a cybercrook. Unsurprisingly, there is much competition and demand for available money mules in the cybercriminal underground. I’ve identified close to two dozen distinct money mule recruitment networks, most of which demand between 40-50 percent of the fraudulent transfer amounts for their trouble. Not only are mule expensive to acquire, they often take weeks to groom before they’re trusted with transfers.

But these mules also come with their own, well, baggage. I’ve interviewed now more than 200 money mules, and it’s hard to escape the conclusion that many mules simply are not the sharpest crayons in the box. They often have trouble following simple instructions, and frequently screw up important details when it comes time to cash out (there are probably good reasons that a lot of these folks are unemployed). Common goofs include transposing digits in account and routing numbers, or failing to get to the bank to withdraw the cash shortly after the fraudulent transfer, giving the victim’s bank precious time to reverse the transaction. In isolated cases, the mules simply disappear with the money and stiff the cyber thieves.

In several recent ebanking heists, however, thieves appear to have sent at least half of the transfers to prepaid cards, potentially sidestepping the expense and hassle of hiring and using money mules. For example, last month cyber crooks struck Alta East, a wholesale gasoline dealer in Middletown, N.Y. According to the firm’s comptroller Debbie Weeden, the thieves initiated 30 separate fraudulent transfers totaling more than $121,000. Half of those transfers went to prepaid cards issued by Metabank, a large prepaid card provider.

Prepaid cards are ideal because they can be purchased anonymously for small amounts ($25-$100 values) from supermarkets and other stores. A majority of these low-value cards are not reloadable, unless the cardholder goes online and provides identity information that the prepaid card issuer can tie to a legitimate credit holder. After that card is activated, it can be reloaded remotely by transferring or depositing funds into the account, and it can be used like a debit, ATM or credit card.

“The information we gather in opening it is the same information you’d be asked if you were opening a credit card account online,” said Brad Hanson, president of Metabank’s payment systems division. “We do checks against different public resources like Experian and LexisNexis to verify that all the information matches and is accurate, and that we have a reasonable belief that you are the person applying for the card.”

The trouble is, the thieves pulling these ebanking heists have access to massive amounts of stolen data that can be used to fraudulently open up prepaid cards in the names of people whose identities and computers have already been hijacked. Once those cards are approved, the crooks can simply transfer funds to them from cyberheist victims, and extract the cash at ATMs. Alternatively, wire transfer locations like Western Union even allow senders to use their debit cards to execute a “debit spend,” thereby sending money overseas directly from the card.

How to Find and Remove Mac Flashback Infections

A number of readers responded to the story I published last week on the Flashback Trojan, a contagion that was found to have infected more than 600,000 Mac OS X systems. Most people wanted to know how they could detect whether their systems were infected with Flashback — and if so — how to remove the malware. This post covers both of those questions.

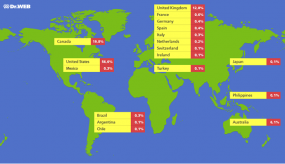

Since the discovery last week of the Flashback Mac botnet, several security firms have released tools to help detect and clean up Flashback infections. Dr.Web, the Russian antivirus vendor that first sounded the alarm about the outbreak, has published a free online service that lets users tell whether their systems have been seen phoning home to Flashback’s control servers (those servers have since been hijacked by researchers). The service requires users to enter their Mac’s hardware unique user ID (HW-UUID), because this is how the miscreants who were running the botnet kept track of their infections.

F-Secure Corp., the Finnish security firm that worked with Dr.Web to more accurately gauge the true number of Flashback-infected Macs, has a Flashback Removal Tool available for download from its Web site.

Where is Apple’s response in all of this, you ask? Apple says it is developing software that will detect and remove Flashback. Inexplicably, it has not yet released this tool, nor has it added detection for it to the XProtect antivirus tool built into OS X. The company’s advisory on this threat is predictably sparse, and focuses instead on urging users to apply a recent update for Java. Flashback attacks a well-known Java flaw, but it’s worth noting that Apple released the Java patch only after Flashback had begun infecting hundreds of thousands of Macs.

Update, 8:22 p.m. ET: Apple just released a new version of Java that includes a Flashback remover. Java for OS X Lion 2012-003 delivers Java SE 6 version 1.6.0_31 and supersedes all previous versions of Java for OS X Lion. It includes no new security fixes, but it adopts a novel approach to the debate over whether to temporarily disable or remove Java: “It configures the Java web plug-in to disable the automatic execution of Java applets. Users may re-enable automatic execution of Java applets using the Java Preferences application.” If the Java web plug-in detects that no applets have been run for at least 35 days, it will again disable Java applets.

Adobe, Microsoft Issue Critical Updates

Adobe and Microsoft today each issued critical updates to plug security holes in their products. The patch batch from Microsoft fixes at least 11 flaws in Windows and Windows software. Adobe’s update tackles four vulnerabilities that are present in current versions of Adobe Acrobat and Reader.

![]() Seven of the 11 bugs Microsoft fixed with today’s release earned its most serious “critical” rating, which Microsoft assigns to flaws that it believes attackers or malware could leverage to break into systems without any help from users. In its security bulletin summary for April 2012, Microsoft says it expects miscreants to quickly develop reliable exploits capable of leveraging at least four of the vulnerabilities. Continue reading

Seven of the 11 bugs Microsoft fixed with today’s release earned its most serious “critical” rating, which Microsoft assigns to flaws that it believes attackers or malware could leverage to break into systems without any help from users. In its security bulletin summary for April 2012, Microsoft says it expects miscreants to quickly develop reliable exploits capable of leveraging at least four of the vulnerabilities. Continue reading

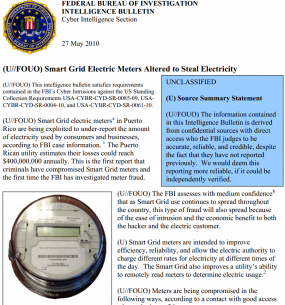

FBI: Smart Meter Hacks Likely to Spread

A series of hacks perpetrated against so-called “smart meter” installations over the past several years may have cost a single U.S. electric utility hundreds of millions of dollars annually, the FBI said in a cyber intelligence bulletin obtained by KrebsOnSecurity. The law enforcement agency said this is the first known report of criminals compromising the hi-tech meters, and that it expects this type of fraud to spread across the country as more utilities deploy smart grid technology.

Smart meters are intended to improve efficiency, reliability, and allow the electric utility to charge different rates for electricity at different times of day. Smart grid technology also holds the promise of improving a utility’s ability to remotely read meters to determine electric usage.

But it appears that some of these meters are smarter than others in their ability to deter hackers and block unauthorized modifications. The FBI warns that insiders and individuals with only a moderate level of computer knowledge are likely able to compromise meters with low-cost tools and software readily available on the Internet.

Sometime in 2009, an electric utility in Puerto Rico asked the FBI to help it investigate widespread incidents of power thefts that it believed was related to its smart meter deployment. In May 2010, the bureau distributed an intelligence alert about its findings to select industry personnel and law enforcement officials.

Citing confidential sources, the FBI said it believes former employees of the meter manufacturer and employees of the utility were altering the meters in exchange for cash and training others to do so. “These individuals are charging $300 to $1,000 to reprogram residential meters, and about $3,000 to reprogram commercial meters,” the alert states.

The FBI believes that miscreants hacked into the smart meters using an optical converter device — such as an infrared light — connected to a laptop that allows the smart meter to communicate with the computer. After making that connection, the thieves changed the settings for recording power consumption using software that can be downloaded from the Internet.

“The optical converter used in this scheme can be obtained on the Internet for about $400,” the alert reads. “The optical port on each meter is intended to allow technicians to diagnose problems in the field. This method does not require removal, alteration, or disassembly of the meter, and leaves the meter physically intact.”

The bureau also said another method of attacking the meters involves placing a strong magnet on the devices, which causes it to stop measuring usage, while still providing electricity to the customer.

“This method is being used by some customers to disable the meter at night when air-conditioning units are operational. The magnets are removed during working hours when the customer is not home, and the meter might be inspected by a technician from the power company.”

“Each method causes the smart meter to report less than the actual amount of electricity used. The altered meter typically reduces a customer’s bill by 50 percent to 75 percent. Because the meter continues to report electricity usage, it appears be operating normally. Since the meter is read remotely, detection of the fraud is very difficult. A spot check of meters conducted by the utility found that approximately 10 percent of meters had been altered.”

“The FBI assesses with medium confidence that as Smart Grid use continues to spread throughout the country, this type of fraud will also spread because of the ease of intrusion and the economic benefit to both the hacker and the electric customer,” the agency said in its bulletin.

The feds estimate that the Puerto Rican utility’s losses from the smart meter fraud could reach $400 million annually. The FBI didn’t say which meter technology or utility was affected, but the only power company in Puerto Rico with anywhere near that volume of business is the publicly-owned Puerto Rican Electric Power Authority (PREPA). The company did not respond to requests for comment on this story.

Urgent Fix for Zero-Day Mac Java Flaw

Apple on Monday released a critical update to its version of Java for Mac OS X that plugs at least a dozen security holes in the program. More importantly, the patch mends a flaw that attackers have recently pounced on to broadly deploy malicious software, both on Windows and Mac systems.

The update, Java for OS X Lion 2012-001 and Java for Mac OS X 10.6 Update 7, sews up an extremely serious security vulnerability (CVE-2012-0507) that miscreants recently rolled into automated exploit kits designed to deploy malware to Windows users. But in the past few days, information has surfaced to suggest that the same flaw has been used with great success by the Flashback Trojan to infect large numbers of Mac computers with malware.

The revelations come from Russian security firm Dr.Web, which reports that the Flashback Trojan has successfully infected more than 550,000 Macs, most which it said were U.S. based systems (hat tip to Adrian Sanabria). Dr.Web’s post is available in its Google translated version here.

Gateline.net Was Key Rogue Pharma Processor

It was mid November 2011. I was shivering on the upper deck of an aging cruise ship docked at the harbor in downtown Rotterdam. Inside, a big-band was jamming at a reception for attendees of the GovCert cybersecurity conference, where I had delivered a presentation earlier that day on a long-running turf war between two of the largest sponsors of spam.

The evening was bracingly frigid and blustery, and I was waiting there to be introduced to investigators from the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB). Several FSB agents who attended the conference told our Dutch hosts that they wanted to meet me, but in a private setting. Stepping out into the night air, a woman from the conference approached, formally presented the three men behind her, and then hurried back inside to the warmth of the reception.

A middle-aged stocky fellow introduced as the senior FSB officer spoke in Russian, while a younger gentleman translated into English. They asked did I know anything about a company in Moscow called “Onelia“? I said no, asked them to spell it for me, and inquired as to why they were interested in this firm. The top FSB official said they believed the company was heavily involved in processing payments for a variety of organized cyber criminal enterprises.

Later that evening, back at my hotel room, I searched online for details about the company, but came up dry. I considered asking some of my best sources in Russia what they knew about Onelia. But a voice inside my head warned that the FSB agents may have been hoping I’d do just that, and that they would then be able to divine who my sources were when those individuals began making inquiries about a mysterious (and probably fictitious) firm called Onelia.

My paranoia got the best of me, and I shelved the information. That is, until just the other day, when I discovered that Onelia (turns out it is more commonly spelled Oneliya) was the name of the limited liability company behind Gateline.net, the credit card processor that processed tens of thousands of customer transactions for SpamIt and Rx-Promotion. These two programs, the subject of my Pharma Wars series, paid millions of dollars to the most notorious spammers on the planet, hiring them to blast junk email advertising thousands of rogue Internet pharmacies over a four-year period.

WHO IS ‘SHAMAN’?

Gateline.net states that the company’s services are used by firms across a variety of industries, including those in tourism, airline tickets, mobile phones, and virtual currencies. But according to payment and affiliate records leaked from both SpamIt and Rx-Promotion, Gateline also was used to process a majority of the rogue pharmacy site purchases that were promoted by spammers working for the two programs. Continue reading